A wonderful six-thousand word essay from 2005…

(Editor’s note: The LA writer and filmmaker Jamie Tierney trailed six-time world champ Kelly Slater for a week during the French leg of the 2005 tour for Surfing magazine. It was considered a fait accompli that Kelly would breeze through a couple of heats and win his seventh world title. The title didn’t happen. The story did. This essay is the only piece I’ve read that comes close to bringing you into Kelly’s insular, and not always pretty, world.)

Four am at the Safari Club. A Friday night, well Saturday morning now, and a bumping little joint in otherwise sleepy Le Penon, France, is off the hook.

Kelly Slater breezes past the door guy and heads down the stairs towards the thumping techno. Normally he’s not the type that likes to hang out in smoky nightclubs, but it’s been a long, difficult day and he’s in the mood for something different.

In the afternoon he surfed one of the worst heats of his career against Damien Hobgood, which blew a chance to clinch his long sought 7th world title. Making matters worse, he then had watch Andy Irons win the Quiksilver Pro France contest to make it a two horse race again.

But now, with all of the day’s angst and frustration behind him, he’s ready for an adventure. He’s going to just roll with it – see where the night takes him.

And besides, just getting here was full on mission. After a quiet dinner with friends, Kelly decided to head into the belly of the beast – Hossegor’s beachfront square where thousands of pro surfers and fans had gathered to drunkenly celebrate the end of the contest. It was exactly the kind scene he’d been trying to avoid all week – too many people wanting a chat, an autograph or a photo. He’d had a few beers in the Hotel du Plage, gave golf tips to Bruce Irons. He even met some people from the Canary Islands with whom he could practice speaking Spanish. But when the bar closed and he walked into the square, the inevitable happened.

Drunk Guy: Can I get a photo with you?

Kelly: Look, if I do one, then everyone here will see the flash and want one.

Drunk Guy: But it’s just one photo I…

Kelly: …I know, but if I do one with you, then I’ll have to do one with everyone.

Drunk Guy (getting pissed): C’mon man, it’s one fucking photo.

Kelly (finger in the guy’s face): You’re not listening to me, if I do one then I…

Drunk Guy: C’mon, just for me.

Kelly: Fuck, dude! I’m so sick of this shit; you’re not listening to me!

The conversation went in circles for another five minutes or so to the consternation of everyone in earshot. Finally, Kelly just threw up his hands and walked away. He headed to a tiny French car where he piled in the back seat with me and four other people he had just met. The driver, an affable local, then threw a surfboard on top and strapped it precariously to the car’s roof with only his leash. Then he fired up the mini Yugo or whatever it was, and we slowly made our way ten miles north to the after-hours Safari Club.

It was fun ride – one of those random things that can happen late at night. But now, at the bar, as I’m buying a round of drinks, another confrontation occurs. This time a born-again Christian has cornered him and is interrogating him about why he’s in this place.

Kelly, of course, realizes the hypocrisy of the question and throws it right back at him. A ten-minute discussion ensues where he calmly explains he’s not religious, but doesn’t have anything against religion or religious people. It’s just a personal choice for him, etc. The born-again guy, meanwhile, (who, by the way, is as drunk as the guy who wanted the photo in the square) isn’t listening because he’s thinking that this is his big chance to convert Kelly. In his mind, this is a huge opportunity, and he’s going for the hard sell.

The bartender hands Kelly his beer. He turns his back on the nightclubbing Christian once and for all. We find a table in the back. He sits quietly and just stares into space for a while. After a few minutes, he gets up and taps me on the shoulder.

“I’m out of here,” he says.

“But how are you getting back to your place – it’s five miles away?” I ask.

“I’ll hitchhike.”

“But it’s five am.”

“Don’t worry, I’ve done it before.”

The point: everyone wants a piece of Kelly and no one likes to take no for an answer.

The problem: I’m one of them.

That’s because I’ve been assigned to write this article. A plum assignment for sure, and, as a life-long surfer roughly the same age as Kelly who has avidly followed his entire career, it’s a piece I’ve waited my whole life to write.

Also, considering what’s at stake, a 7th world title, it’s a golden opportunity to depict an intimate view of perhaps the most pivotal moment in the greatest surfing career of all time. But I can’t help but thinking how difficult getting this done could be.

First of all, he doesn’t need it. It’s not like being on the cover of this magazine again is going to help his career. He also doesn’t need the distraction of someone asking for exclusive interviews and photos during such a pressure packed week. He could easily tell me to take a hike.

Making matters worse is Kelly’s reputation for being, shall we say, elusive. Journalists and photographers love to tell stories about futilely trying to chase him down for an exclusive. One poor guy from Sports Illustrated once flew to Hawaii for a week to write a profile and got completely skunked.

In the right mood, he’s one of the most affable and accessible surfers in history, but when his frame of mind darkens or he gets distracted, he shuts down and turns aloof. Finding him or pinning him down to any sort of plan then becomes nearly impossible.

At the beginning of my trip, Surfing’s photo editor, Steve Sherman. and I go to dinner where we discuss the mission at hand.

“We’re here to stalk Kelly,” Sherm says. “We’re not leaving him alone until we’ve got the goods.”

We talk about the weapons on our side. First, is a little blue blackberry. Kelly loves cellphones and email, and my little pocket rocket can reach him on either anywhere at anytime. In case that doesn’t work, I’ve also got a host of his friends’ and Quiksilver employees’ numbers on speed dial to determine his location at any given time.

Second. He loves golf and I’ve been playing since I was two years old, which means that if I’m on I can beat him. He loves competition so chances are good we’ll be meeting up here to play.

Third. He’s liked and respected Sherm for his whole career. He should, considering Sherm’s snapped many of the most iconic images of him. There’s no one in the world he’d rather have photographically documenting these heady days.

Fourth, I know where he’s staying (at an estate in Capbreton) and if all else fails we can put emergency measures into place and just post up outside the wall and wait for him to come out in full hideous paparazzi style.

I first see Kelly at the press conference at the start of the contest and he’s not happy. After all, he’s just disembarked from a 12-hour flight from LA and now he’s facing a room full of cameras and a firing squad of foreign journalists known to ask ridiculous questions.

The first one is a doozy: “Kelly, is it your goal this year to win the world title?”

Kelly gives him a look that says, “Are you freaking kidding me?”

Andy Irons and Dane Reynolds, sitting next to him, look away and chuckle. Then, Kelly responds with tension audible in his voice, “Of course it is. The goal is always to win a world title.”

It gets worse. Nearly all the questions are for Kelly – Andy and Dane just have to sit there uncomfortably – and all are idiotic.

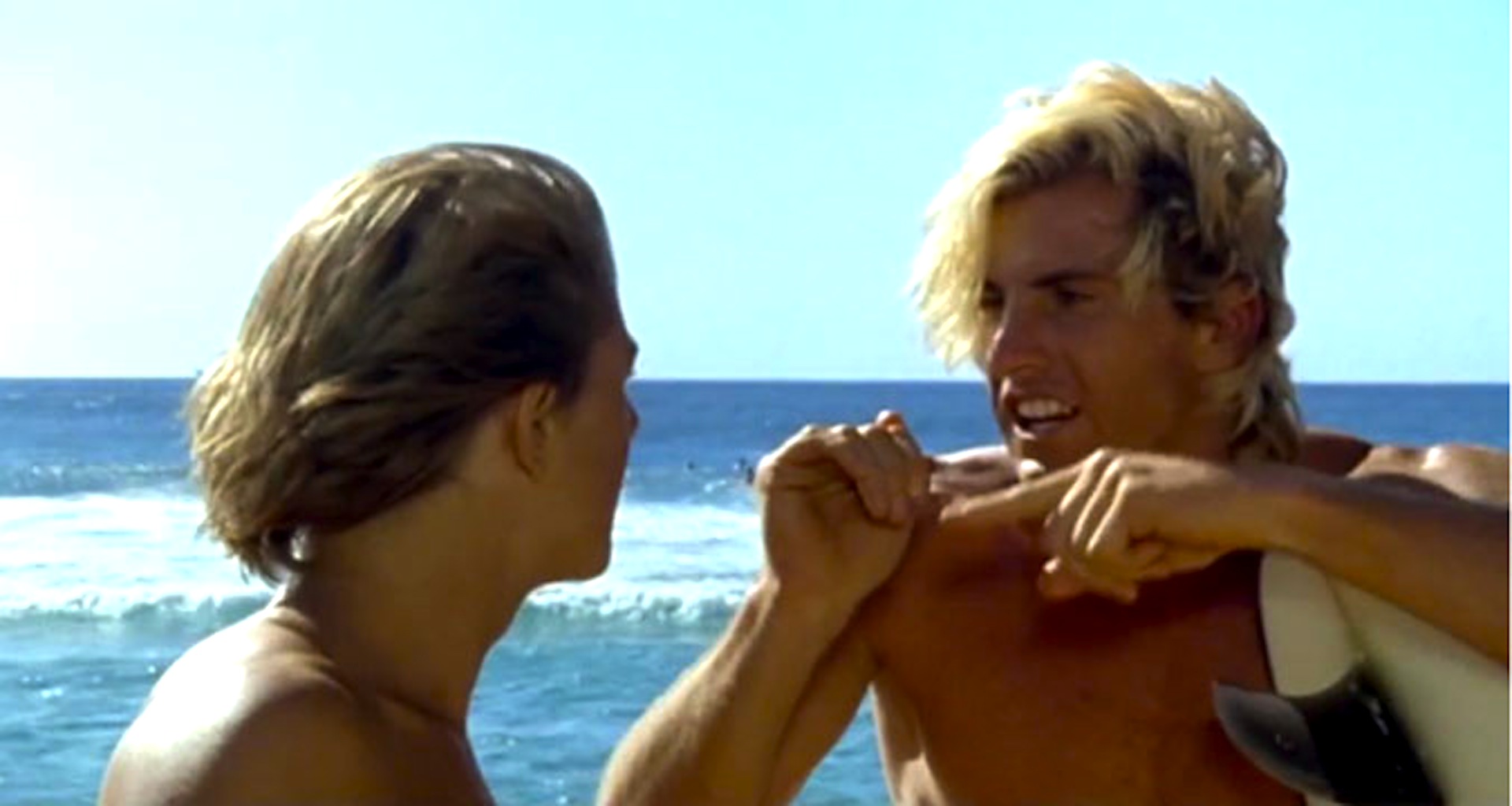

The worst of the lot is from a bleached blonde Spanish “journalist” (later seen in a full-on make out session on the couch at Rock Food with a drunken member of the Top 44) who asks him, “Kelly, what is your relationship with the ocean?”

His incisive reply: “I don’t know how I can answer that without sounding corny.”

The next day, though, he’s more at ease. The surf is small and onshore so it’s a golf day. He picks me up in his rented high-end Volvo (a surprisingly zippy machine) at the Les Estagnots parking lot, and we head a to beautiful course in the middle of a pine forest. Kelly plays golf the way you’d expect – aggressively but carefully. He’s gotten his handicap down to the mid-single digit range. (A level where one can play with anybody in the world and not embarrass oneself.)

Today, however, we’re forced to use a rental half set and both of us (me especially) have a shocker. At the end of the round, I try to get him to discuss the real possibility of clinching the title here and the plans for the celebration.

He gives me a few vague answers to my questions and then shuts down again. The bitter disappointment from losing at Pipe in 2003 is still clear in his mind. After his emotional win at Trestles a few days ago, virtually the entire surfing world began to look at #7 as a done deal. Andy even said as much at the press conference yesterday.

“I know I pretty much have no chance now but I’m going to keep trying anyway,” was Andy’s reply to the only question directed his way.

Kelly, however, knows this thing is far from over – Andy’s at his most dangerous with his back to the wall – and the worst thing he can do right now is get ahead of himself. As he thinks about this stuff, he starts driving faster, pushing the Volvo to the max and ripping through the narrow and twisty French roads. The display seems intended to make me nervous. But it’s cool, he’s obviously a good driver and I’m fine with it.

“As you can see by the way I drive, I’ve been here before,” is all he says.

We go to dinner at Pinocchio’s near Hossegor’s seaside square and his mood brightens. His close friends, Gabe and Lauren, a down to earth surfing couple from the UK, join us. We eat foie gras and moules frites, and the wine and conversation flows naturally.

Kelly is the first celebrity pro surfer, and he’s known to pal around with the likes of Pamela Anderson, Cameron Diaz, Jessica Alba and Giselle, but it’s clear tonight that he’s most comfortable with normal folk. It’s also nice to see that he likes spending time with two people who are clearly in love. It doesn’t take much psychological insight to see that, as the child of a broken home, he wants their love and happiness to rub off on him. He’s dealt with his share of romantic turmoil (publicly in the case of Anderson). Women have always been his Achilles Heel, but he still believes in the value and possibility of sustainable love. I also think he likes being around Gabe and Lauren because it reminds him that relationships don’t have to be so complex, confusing, or difficult.

The next day, he shows up at La Graviere for his Round 1 heat just as a new swell starts to pulse. He opts against surfing a soft right up the beach for a grinding, semi-closeout in front of the scaffolding. His opponents, Luke Egan and Jeremy Flores, see what he’s doing and decide at the last minute to join him. After a slow start, Kelly’s at his best, expertly threading his way through throaty tubes en route to a commanding win.

Watching him surf one is immediately impressed by his explosiveness and spontaneity. He still has the hunger to try new things and push his limits all the time. He knows how improbable his story is – the son of an alcoholic dad and struggling single mom from a virtually waveless beach in Florida somehow becomes the greatest surfer of all time.

But how did he do it? That’s always the question. He knows he’s been given this incredible gift. Many people, surfers especially, who are supernaturally talented are inclined towards coasting and resting on their laurels. They’re comfortable knowing that their genius expresses intermittently or in fits and starts.

Kelly, on the other hand, wants his surfing to be perfect all the time. He’s hell bent on proving he’s the best, not once a year or once a month, but on every single wave.

After his heat, instead of bailing to his pad or to the golf course, he decides to stick around the competitor’s area and see what the swell’s going to do. He’s been coming to this part of France since 1989 and has a knack for knowing when these fickle and ever changing beachbreaks are going to turn on.

At five pm, when the contest is called off, his hunch pays off. When the final horn blows, he sprints down to the water’s edge and dives in. No longer the complicated 33-year-old man, he’s a Floridian grom again, paddling out to waves that are akin to a once-in-a-lifetime hurricane swell back home.

The large crowd on the beach then does something I’ve never seen at a surf contest. The heats are done for the day, but no one’s going home. That’s because Kelly Slater is in the water, and the showman in him has taken over.

In the gauzy soft light of an endless French dusk, he’s dropping into one double-overhead, below sea-level bomb after another, pulling up under the curtain and touching the roof with outstretched fingertips. It’s beautiful and stirring to watch – his trademark white wetsuit looks like it’s glowing from within. The crowd can’t get enough of it, cheering his every wave and staying on the beach until the light is all but gone and he paddles in.

A few minutes later, wide-eyed and still buzzing with adrenaline he calls the session, “The best surf I’ve ever had in France.”

It’s the peak moment of his world-title campaign here. But the problem with peaks is that once you reach them, there’s nowhere to go but down.

And, as he excitedly chats with Timmy Reyes and Shea Lopez in the otherwise deserted competitors’ area, a funny thing happens. The hundreds of spectators that were watching him surf are now watching him…towel off. It’s weird and disturbing. It reminds me of Matt George’s infamous “Kelly Slater Sleeps Like Angel” profile from 1989 where surfing’s gonzo journalist began his piece by recording his impressions while sleeping in the same bed with a then 17-year-old Slater.

I’m getting the same creepy feeling now that I did when I first read that article. People here are just blankly staring at him from behind a metal barrier fifty feet away. Kelly doesn’t pay any attention to it, but I try to figure out what it means.

Why is he by far the most popular ever? What sets him apart? Maybe it’s because he’s smart and interesting. In an age when most of the Top 44 went the home school route, Kelly not only graduated from high school, but earned straight A’s. He’s one of the few pros who would have made himself a success even if his father had never taught him how to surf.

But there’s something else that I’m starting to understand. I’m noticing that the person in front of me isn’t a human to these people. He’s a superhero, a creation, a thing. And I’m realizing though that this “Thing” isn’t the creation of the fans, the public or the media.

It’s something Kelly created on his own.

My “Thing Theory” comes from something Cindy Crawford said about ten years ago. The jist was that when she woke up in the morning she was a normal person. But in order go to work and become the “top supermodel in the world” she had to transform herself into something she called “The Thing” – the creature with perfect hair, perfect teeth, makeup, clothes – the works.

Kelly’s the same at a surf contest. In order to do what he does best (win contests, break records, rack up world titles, give great victory speeches) he’s got to transform himself. The Thing is superhuman, but the person underneath is different. he Thing doesn’t read Noam Chomsky, play the ukulele, study alternative medicine or speak Spanish to strangers, but the person does. The person is more interesting and it’s him that I need to see more of while I’m here.

I see a glimpse the next day. We’re on the golf course again and Sherm’s taking photos. It’s clear Kelly’s not real happy about this but knows we’ve got a job to do. We’re putting on the fifth green when a statuesque woman with long blonde hair, thigh-high riding boots and two large dogs saunters towards him. It’s straight out of a James Bond movie. Kelly and the woman have an awkward two-minute chat and then it’s on to the next hole.

Because Sherm has enough golf action in the can, he stops taking photos. Kelly’s game improves as does his mood. At the end of the round he invites us to check out an ASP meeting at the Rock Food.

On the road in Sherm’s tiny French rental, we talk about the mission so far. We agree that we’re making progress. Yet we both wonder what lies ahead. Is winning the world title here the done deal that everyone’s making it out to be? With a big swell on the way, we’ll find out in the next few days.

At Rock Food, we walk into a surreal scene that’s becoming more and more common. Members of the Top 44 are drinking beer and socializing while Kelly and Andy Irons are in a back corner quietly talking. Sherm snaps a photo and then leaves them alone.

The two couldn’t be more different: Kelly – the cool, polished, silver-tongued ambassador versus Andy – emotional, macho and plainspoken. In 2003, the heat of battle turned them into enemies. When Kelly whispered, “I love you” to Andy moments before their final heat at Pipe, it was viewed as the ultimate psych-out attempt from a guy who’s a master at reducing his opponents’ heads to jello. And it didn’t work. Kelly probably respects Andy so much because he’s never been able to get Andy to take the bait.

Later on, I ask Kelly if the game’s more fun now than it was during his six-titles in seven years run in the ‘90’s because now he has a true rival.

“It’s good to be challenged,” he says. “It wasn’t like I felt like I wasn’t challenged back then, just not consistently. One year it was Rob and then Sunny, and one year it was Beschen. It was different each year. It wasn’t someone like Andy who pushes himself as far as he can all the time.”

At La Nord the next day, the challenge comes from an unlikely source, a small 17-year-old wildcard named Jeremy Flores. The waves are mental – 10-foot heaving barrels over an insanely shallow and rock-hard sand bar. Young Jeremy charges. He gets an incredible wave at the start of the heat and assumes control. The pros in the competitors’ area go nuts, sensing a big upset is at hand.

Earlier in the year, at Teahupo’o, Fiji and J-Bay, he felt like his peers were rooting for him. But something changed when he won again last week.

“You can just feel a subtle switch,” Kelly tells me. At Trestles, I had won four events and guys were saying, ‘Okay, that’s enough.’”

Sure enough, cries of “bullshit” fill the air when Kelly gets a smaller wave which scores higher than Jeremy’s. Kelly then gets a solid backup while Jeremy pulls into giant closeouts and waves to the crowd. Kelly wins the heat fair and square but seems rattled when it’s over. The Thing is gone, replaced now by a tense, anxious person.

“I had to work my ass off out there,” he says.

His tension grows exponentially in next few minutes while watching Andy’s heat. Andy’s opponent, a Kiwi journeyman named Maz Quinn, takes a big lead. Suddenly to the surprise of everyone, it is revealed that Kelly will seal the title right now if Andy loses. Traffic on the live webcast goes crazy, shattering records. Behind the scenes it’s even nuttier – cameras are converging around Kelly and are recording his every gesture. For the first time in anyone’s memory, he snaps. “All of you just need to step back and give me some fucking room here!” he yells.

In the end, Andy stages a comeback and Quinn’s unable to find the mediocre score of 3.43 he needs to win the heat. Andy’s still alive, but looks shocked and drained from the experience. So does Kelly.

“If only Maz hadn’t dug a rail on his last turn,” is all he says.

Andy’s brother Bruce tries to cheer him up. A few weeks ago at the Surfer Poll Awards, Bruce got up a stage and drunkenly said over and over, “Kelly Slater is my favorite surfer.”

The display was widely viewed as a direct dig at a brother he’s been known to feud with. Today, as the surfers file away, Bruce looks at Kelly and says, “That was just a fire drill.”

The implication is clear. Bruce thinks he’s going to win the world title this year and he’s going to clinch it here. It’s an interesting sentiment considering that Bruce’s next opponent will likely be Andy in the quarter-finals.

The following morning, the surf is still solid, but an early onshore wind turns it to slop. Kelly shows up mid-morning and surfs the expression session. He’s relaxed and chatty and has his trademark competitive mojo going. The Thing is back. When he sees Maz Quinn he looks right at him and says, “I haven’t seen many heats where a guy only needed a 3.43 and couldn’t get the score.” The remark is clearly devastating to Quinn who just stands there, looks away and says nothing.

That night Sherm and I see a different side of Kelly’s life – the privileged one. We happen upon a soiree taking place at the gorgeous house of Pierre Agnes, the head of Quiksilver Europe. Kelly’s staying here in a killer guesthouse by the pool and this event has been held in his honor. John Cruz, one of his favorite singer/songwriters, has been flown in from Hawaii with Titus Kinimaka just to perform for him.

While all the power players in European surfing sip on champagne and eat Asian tapas, a stone-sober Kelly sidles up next to the Cruz, plays the guitar, and sings his heart out. He’s clearly in a zone, feeding off Cruz’s soulful, heartfelt lyrics and psyching himself for what’s to come tomorrow.

Nine am at La Nord: Kelly paddles out. It’s the final day of the contest and he knows what he has to do to clinch the title: finish higher than Andy. Yet he looks shaky against Brazilian Paulo Moura. Moura builds a lead at the beginning the heat with a decent tube ride, but Kelly’s able to get two decent scores and posts a fairly easy win. Andy paddles out next against Occy and goes nuts. He gets an incredibly long tube ride and rips off one of the best backside off the lips ever seen in competition. The message is clear: Andy’s forgotten all about his near loss to Quinn and is on fire today.

A couple hours later, the contest moves to La Graviere where Kelly had his magical session after the end of Day one. He’s up against Damien Hobgood and gets killed. Afterwards, he says, “I did everything wrong in that heat.”

Backstage, all the pros leave him alone and give him space to think things over. The next heat paddles out: Andy vs. Bruce. Kelly thinks that it doesn’t matter because he’s already lost any shot at clinching today. Not the case, he’s soon informed. If Bruce can take out Andy, Kelly will still be the new champ. It’s a flickering hope, but it soon disappears. Andy gets the first 10 of the contest on his opening wave and rolls past his brother, and later the rest of the field on his way to victory.

The rest of the day Kelly sticks around and does webcast commentary. He admits to Pottz that he’s “bummed,” but the Thing is still in full effect.

His comments are analytical, reasoned, un-emotional. He looks at the message boards and reads countless emails offering him support and encouragement. What’s interesting is what he doesn’t see: traffic numbers. After his loss, the number of people watching the live webcast plummets. In cyberspace, just as it is on the beach here, the overwhelming majority of fans want to see him win.

It’s easy to be envious of him for a host of reasons: talent, looks, wealth, fame, globe trotting lifestyle. He says that one of the most common questions he hears from strangers is: “Want to trade lives with me?”

But sometimes his existence isn’t always as idyllic as it seems. Here he is, racing around the world, pushing his surfing as far as it can go in what is likely a final attempt to vanquish an indomitable opponent. But he’s doing it all by himself – no partner, no family, and few friends. He’s not part of the tour social scene anymore because all of his “New School” buddies (save Taylor Knox) have retired. He’s also just getting to know his eight-year-old daughter in Florida, and let’s face it, in moments like these he’s lonely.

I wake up late the next morning with hazy memories of last night’s weirdness at Hossegor square and the Safari Club. The contest is over, but there is a job to do. Sherm needs to take photos for a cover portrait shot while I need to sit down with Kelly for a formal interview. I meet Sherm at the Patisserie du Golf in tony Hossegor Ville and try to call Kelly on my Blackberry. I get no answer; I expected this, he’s probably still asleep.

Sherm and I hang out and people watch – our shared anxiety growing. Sherm reckons that the light is perfect and fears that if we don’t shoot him today he might decide to bail for the Caribbean, Tahiti or Hawaii tomorrow and we’d be screwed. I send him an email and try his friend Stephen Bell (Belly) the Quik European surf team manager. Nothing works and so we move on.

We post up in the Hotel du Plage with a group of executives from Quiksilver International. We sit around and trade “waiting for Kelly” stories. We’ve all been through this before. It goes with the territory.

At five pm, we’re still there. I finally get a hold of Belly. He tells me Kelly’s decided to play a late round of golf. “Sorry, mate, no photos today,” he says.

Sherm and I both sigh, resigned to writing off today as a failure. I try to rationalize, thinking that it’s better that this didn’t happen. We didn’t have any fixed plans and I know that if Kelly’s not in the mood, then we’re unlikely to get the quality shots and quotes we’re looking for. I look out the window at the ocean and see storm fast moving into the Bay of Biscay. His golf game is going to get rained out. I smile. I have a hunch that Karma’s back on my side.

My hunch proves right. I get him on the phone the next day. I wake him up and get right to the point. “Look, Sherm says this will only take an hour. If you can do this we’ll promise to leave you alone.”

A pause. “Put Sherm on the phone,” Kelly says.

We arrive at the Agnes property. Kelly opens up the fifteen-foot high wall and lets us in. It’s a crisp and bright French fall day. Beautiful. We sit down in the guesthouse and he starts playing the ukulele. The Thing is nowhere to be found. In its place is a warm, thoughtful, engaging person. Sherm takes us to an underground parking garage that’s under construction next door. He thinks the overhead natural light will create the perfect conditions for one of his trademark moody black-and- white portraits.

Kelly sings as he poses – digging on how his voice echoes through the concrete. While he won’t flatly state that he will retire if he wins, it’s clear that slowing down is on his mind. He wants to settle in Hawaii, build a house, and have a normal life. He gets excited and imaginative talking about the prospect.

“I’m thinking about building a house made of a train, a plane and cars – like a series of Airstreams. There could be a gutted airplane or even just part of the plane. The cockpit could open out or turn and I could put a breakfast table that overlooked the ocean. Two or three train cabins could be bedrooms. It would be extreme opposites, modern technology and nature. A lot of these old planes and trains are just rotting in the desert. I might as well get some use out of them. It would be so much fun. I could hand out boarding passes to people when they came to visit.”

It’s an interesting idea. He currently doesn’t own a house and building a new one based around travel says something about him and where he feels most comfortable. Since he was 12 years old, he’s figuratively lived in planes, trains, and automobiles. Now, he could literally make them his home.

Sherm gets to work quickly in the parking garage amidst our discussion and within minutes he’s buzzing – confident he’s got the photographic goods. We head back to the house and keep talking. I tentatively bring up my Thing theory and hope Kelly won’t be offended by it.

Instead it’s the opposite – embraces it.

“Any person who is a sports star or a musician – it’s imagery,” he says. “You do become a thing as opposed to a person in some sense. Not completely, but there is a big element of that. It’s easy to get caught up in that and be the Thing all the time.

“I used to feel a real obligation to be the thing at all times. And now if someone crosses the line I let them know and I don’t feel guilty about letting them know it. Whereas before I thought, oh they don’t understand. But you know what? Sometimes I don’t understand them either. I have emotions like anyone else, and if I don’t show them then I bottle them up and get all frustrated. It’s like that situation we had the other night with the guy who wanted the photo. I’m a person and that guy’s a person, and in one way, he wants to connect with me. He wants something – a human connection, but on the other hand, he wouldn’t connect with me or listen to me or let me talk to him. He just wanted what he wanted and didn’t want to listen. So I was like, well then, screw you. I’m trying to be one-on-one with you, but you won’t listen to me even though you want all my attention.

“When you get to a place like here where you’re only in town for one week a year and everyone knows that and no one knows how many more times you’ll be on the street or in this or that restaurant or whatever. And there’s this thought that I have to do this because maybe I’ll never get to meet this person or get a photo with him again. We all probably have a couple of those people that we feel that way about. If I met Nelson Mandela for instance, I’d totally want to get a photo with him.”

The interview gets around to topics of family and relationships. He says something about his mother that I find touching in light of his father’s death in 2002.

“My mom always put out this really hard, cynical, sarcastic thing. She still tries to put that out but her new boyfriend doesn’t believe that about her. She doesn’t know what to do with herself. She’s like, ‘What do I do now? Somebody loves me. I tried to push everyone away and now this person won’t leave me alone. He sees all these things about me that I always wanted someone to, but I never thought they would.’”

With all the heavy stuff behind us, we decide to chase surf and have fun for the rest of the day. The surf has come up again but is onshore and stormy. We head south on the peage looking for a more protected spot near the Spanish border. We lose sight of Kelly on the highway as he bursts ahead of us. We think we’ve lost him again, but then he calls a few minutes later and gives us perfect directions to the spot he wants to check. He’s still being elusive and yet accessible at the same time.

After checking half a dozen spots, we finally settle at the north corner of Anglet next do a McDonalds. We sit inside the golden arches and trade Ali G impersonations while waiting for the tide to drop. We wander along the windswept beach, and Kelly taps Sherm on the shoulder.

“Can I be photo editor for a minute?” he asks. “See the way the beams of light are shining down at the end of the jetty. Can you take a photo when a big wave breaks and explodes into that light?” Sherm smiles – it’s a great idea.

“Okay, now!” Kelly says. Sherm snaps the shutter.

A few minutes before dark, Kelly puts on his wetsuit and walks towards the ocean. He may not have gotten the title here but it doesn’t matter because right now he’s going to do what he loves. Surfing is his salvation. It brings the thing and the person together. His reawakened stoke for the sport has given him one last magical year on tour.

He’s happy now. He’s going surfing.