Hello sweetheart!

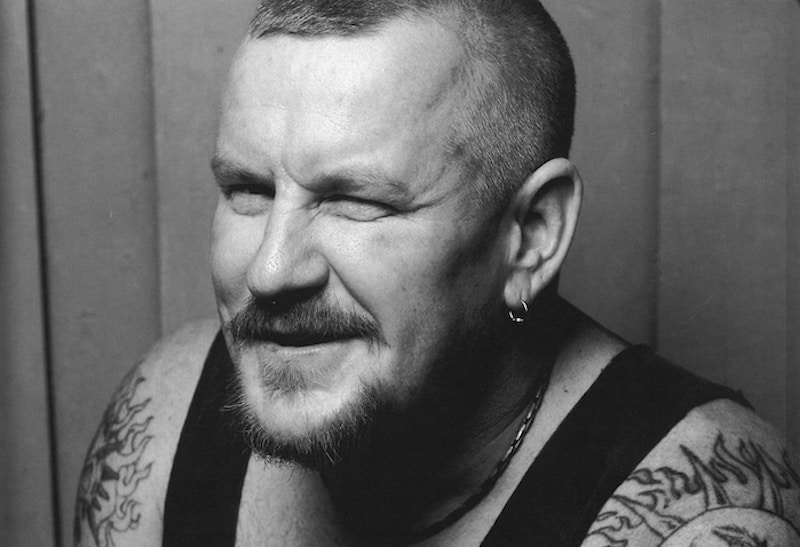

(Editor’s note: Six years ago, I commissioned the noted Fred Pawle to write a story about the surf photographer Paul Sargeant’s misadventures, which had included a sexual assault on a journalist. While that story was back and forthing, and at one point stalled because a former Tracks editor said Sarge would kill himself if it ran, I offered Fred the slightly more uplifting story of surfing’s first openly gay pro, Matt Branson. Openly gay in the sense that long after retirement, he’d come out.

In contrast to the hoops Fred was jumping through to get the Sarge story, Branno answered his phone on the third ring and invited Fred to his home on the Gold Coast for the interview. Arriving with a case of beer on his shoulder – oowee, Branno likes to drink – the pair got boozed and, according to Fred, within ten minutes he’d recorded every significant quote he needed.

As the writing of the story progressed it transpired that, as a teenager, the closeted Branno had been involved in hassling gay men around public toilets. Fred called Branno, who wasn’t real thrilled with that detail being included in the story.

Fred don’t do half-truths, however. And the story, which I called The King of Queens after a popular TV show at the time, was feted by the mainstream press and nominated for a Walkley Award, the highest honour in Australian journalism.

If you want to read the entire four thousand word story, click here, but for those of you with an abridged attention span, here are the highlights…

Hassling homosexuals

Branno says it was “just disgraceful”.

“We were 16 or 17. It was a pack mentality, and me going along with it all. My mates are straight, to the core. They are a pretty extreme crew, and I was one of them. I grew up in the same environment. I was thinking, ‘If I do this, then I’m not gay.’ I knew what I was inside and I thought by doing it I wouldn’t be like this anymore. It’s a real black spot in my growing up. But remember, this was 20 years ago. The world was a totally different place.”

Branno is reluctant for this detail to be written about but he agrees after I explain that it illustrates not only his inner trauma but what was at stake for him to come out. His oldest friends, who in every other way were his soulmates, were virulent homophobes.

“I don’t think they even realised what homophobia was,” he replies. “It was just, ‘Who are these guys? Let’s bash them.’ Knowing they were strange to their life. I don’t want my friends to be seen as opposed to what I was as a person. That’s an immature way of thinking. My mates hadn’t developed then. They weren’t their own men. I’m the luckiest man in the world to have the friends that I do.”

“It was fucking incredibly hard. You always felt like you were lying. You always felt like you were putting on a charade. As a young person growing up, to have that charade, it can fuck with you because you can’t grow as a person.”

Post tour

If you want the short version of the story, it goes like this: Branno dropped off the tour in 1991, started playing in a punk band, worked as a dishwasher (then as a council worker, now a glasser for JS), moved in with a boyfriend and over the next few years told some close friends and family. Some took it hard and spent a long time getting used to the idea. Other’s brushed it off because it didn’t matter. Either way, as word spread, the immediate response from everyone was, “Bullshit! Branno? But he’s the last bloke…” Now he and every one of his friends are cool with it. He’s been approached by other magazines over the years to tell the story but declined them all partly because he feels uncomfortable talking about himself. He’s only doing it now because he’s finally, as he approaches the age of 40 (Branno is 38) content with who he is, and wants other young kids who are trapped in the potentially suicidal hole in which he spent the first 25 years of his life to know that it’s okay. He’s got a point there. Let’s face it, if a dude like Branno can come out, anyone can.

On his punk image

“Branno pioneered the whole surf-punk thing on tour with the tatts and all that stuff,” says Sunny Abberton, a fellow member of Rusty’s “dirty half dozen”, as he calls it. “To travel with all those guys was great but I don’t know how good it was for my career. He was the first one to say, ‘Fuck the rules, I’m doing my own thing.’ He was the first in the modern era to be influenced by things outside surfing.”

“Branno and his mates were raging against the machine that was pro surfing,” says Matt Hoy, two years Branno’s junior, who went on to refine the surf-punk image even more. “I looked up to him because he didn’t give a fuck. He’d do what he wanted to do and still go out and rip when he had to.

“When we were on the tour, half the guys wouldn’t even speak to us. We wanted to see the world and live the dream, hang out with as many people as we could. We wanted to live every part of the dream not just the surfing part of it.”

“Branno was the type of guy who would turn up late for a heat hungover, borrow a board and blow people away,” says Mogga Sutton, Rusty’s team manager at the time. “That was a big time for us. The grunge-headbanging thing was happening. It was part of where we were as a brand. They were all great surfers but our philosophy has always been that they’ve got to fit in with what Rusty is all about. We’ve always done things differently. It was more about image and having a good time. And Branno was totally there. He totally crossed over.”

Imagine, therefore, the turmoil in Branno’s head. “I loved it,” he says. “I loved where pro surfing was going. But my whole trip was different inside my head because I was gay. I’d get a bit of exposure in a magazine, I’d see that and go ‘fuck!’. And then it sort of snowballed. People started to know me off the street, and I’m almost getting more paranoid. Like, ‘Oh my god, this person thinks I’m this, this person thinks I’m that.’ And I’m sponsored by Rusty, and they’re promoting me this way, which is what I am, basically, no worries about that, but imagine if the fucking hammer comes down and someone found out that I’m gay. What would that do to these companies? Think about that. That’s what is going through my brain. Sitting there, right, Rusty is paying me to go around the world and promoting me, and West Suits are doing the same; two companies that I fucking love, and the guys who work with them are really cool, they are promoting me as their number-one guy. Imagine if they found out! It would send these fucking companies down the gurgler almost.”

On almost being murdered in a toilet

On April 15 1991, filmmaker Tim Bonython and a few others left a Tracks party in North Sydney to drink on in Kings Cross. It was a Sunday night and the options were limited. “We ended up at a seedy underground bar run by the mafia,” Tim says. “It was the devil’s armpit. The scum of the Cross would go there. But when everywhere else is closed and you’re partied up, you’ve got nowhere else to go.”

Tim remembers thinking Branno had gone missing for a while. Then he saw him emerge from the men’s toilet, stumbling through the crowd. “He looked a bit sick, a bit weird, then I heard someone say, ‘He’s been stabbed!’ I ran out to the street and got him just before he was about to collapse. He just wanted to get out of there. He started going into shock looking a bit sleepy. His eyes were floating around in his head. There was blood all over him. He had holes all over his body. He was fucked up. We both sat down and I yelled for someone to ring an ambulance. I just remember trying to comfort him. I was scared for him but I was confident he was going to stay with us. I didn’t know how to deal with it. I’d been partying since about 8pm. We were in our tenth hour of partying and numb to the reality of what was going on. I just kept saying, ‘You’ll be right, mate, just keep breathing in, keep it together.’ I remember keeping him buoyed up, keeping him confident.

“I’m glad I was there for him. He would have been more fucked up if he didn’t have anyone he knew. A lot of the other guys were so freaked out, they had to disappear. Nobody wanted to be caught up in it. It didn’t worry me. I was definitely there for Branno till I knew he was going to be okay.”

Tim rode in the ambulance to nearby St Vincent’s Hospital and stayed in emergency till they wheeled Branno into surgery.

Hmm. Gay dude attacked by psycho in dunny of a seedy bar. I know what you’re thinking, and you’re wrong. “It definitely wasn’t sexual,” Branno says. “I’d tell you if it was – I’ve got nothing to hide.” In fact, it was a case of mistaken identity. An earlier exchange with a Tongan dealer at a nearby, equally seedy bar had gone wrong, and the dealer had come looking for a blond surfer kid, someone who happened to look like Brando. “I didn’t even see the guy,” Branno says. “He came in and hit me. My head hit the top of the urinal. I turned around and – bang! – he had a knife.” Branno was stabbed in the neck and stomach. His thumb was almost severed from trying to stop the dealer ripping his guts open with it while he screamed, ‘Stop it! You’re killing me! What have I done? What do you want?’”

The dealer was convicted of another crime soon afterwards and bragged to an inmate that he’d almost killed a surfer in the Cross one night. Word got back to the cops and Branno was brought in to identify him. He couldn’t. “All I could remember where his eyes,” he says. “His eyes had death written all over them.” Last Branno heard, the dealer had been deported back to Tonga.

Coming out

The first person Branno came out to was Will Webber, who he’d known for five years. The Webber family home in Rose Bay, Sydney, had been a regular stop while Branno was on tour. They were all serious punks. When Will visited him in hospital after the stabbing, he brought along the Fender Strat he’d just bought, his first guitar. Branno had for years been dabbling in punk bands, as a diversion from the tour. Now that he was off the tour he, Will and his brother Ben could start their own band. Mindcrack went on to become underground legends. Branno chose Will to be the first person to hear his dramatic secret. They were on a bender, as usual, when he made the announcement.

“I remember we were having a sword fight in the toilet,” Will says. “I was talking about trippy things like space and time and stuff and he said, ‘I’ve got something to tell you that’s going to blow you away.’ I said what, and he just goes, ‘I’m gay’. Strangely enough, the first thing I said was, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Don’t say that!’ I said, ‘Sorry mate, that’s fine,’ and gave him a big cuddle.” Will happily kept the secret for years.

Branno knew the next stage would not be as easy. Neither was it avoidable. “I still needed that acceptance from WA because that’s where I’m from,” he says. A few years later he wrote to Manners, starting the letter with a warning that he should be sitting down when he read it.

“I remember the day,” Manners says. “We used to write to each other all the time. We were like pen pals, that’s how close we were. The letter said, ‘I’ve got something to tell you: I’m a fag, I’m a poof, I’m a homo.’ I was in shock. He asked me not to tell anyone. So I just quickly tore it up and put it in the bin so nobody would see it. I had this secret that was spinning me out and wasn’t allowed to talk to anyone about it. He rang me after a week or two and said, ‘You haven’t rung me.’ I said, ‘If that’s your fucking choice, you made your bed you sleep in it.’ I was hanging out with bikers at the time, everything was pretty tough and rugged. That was the scene I was in.”

Branno, living on Sydney’s northern beaches by now, was devastated, and called Will over. “He was crying his eyes out,” Will says. “He was shattered. I just told him I would be by his side forever. It was a powerful moment. I didn’t think he would make it through the night. When someone’s world falls apart, especially a man, and a man’s man, it’s almost inevitably suicidal. Then I said, ‘You know what you’ve got to do, mate? Let’s call your parents now.’ We did it at night, while I was there. When he got off the phone, it was like a new beginning.”

“I was shocked but I kept thinking of the pain he must have been going through all those years,” Jan says. “And I didn’t understand the gay thing, it just didn’t compute in my brain. But I just had to continue to show unconditional love and support.”

Will then turned his attention to Manners. “The Webber brothers rang me up and said, ‘What are you doing, man, writing your best mate off?” Manners says. “Both will and Ben rang me up and had a go at me. I just thought my response was normal. I was like, ‘What are you doing accepting this? I guess in Sydney it was a lot more accepted at the time. I was just thinking about myself. I didn’t for a second think about what Branno was going through.”

Some time later, Manners was out at a night club with some friends, and one of them took him aside. “Is Branno your friend or isn’t he?” he said.

“Well… he’s my fucking friend,” Manners replied.

“A light switch on,” he recalls now. “I just felt all the love in my heart for him and ran outside and rang him up.”

“He had to deal with it in his head,” Branno recalls. “I was hurt but I understood the response because of the background my mates had come from. They’d never had dealings with anyone who was gay. But that’s what you’ve got to do when you’re gay. You’re always scared you are going to lose your mates.”

Richard Kelly, another member of the Perth punk crew, found out indirectly and drove 4000km to Sydney to get it straight from Branno’s mouth.

“I just drove over there without telling him, knocked on his front door and said, ‘What the fuck is going on, mate?’ It wasn’t so much, ‘How come you’re a poof?’ I just wanted him to explain what was happening. I thought all of us deserved someone to go over there and ask him.

“We sat down and had a beer straight off the bat. He tried to explain how his brain was going through it. It wasn’t the time for me to go, ‘Oh, that’s shithouse.’ I went, ‘Whatever you reckon, mate.’ The conversation probably went till the beer ran out. We probably went for a surf the next day. Life was normal. I just left it to him, whenever he wanted to tell me about it. What can you do? There was no way, him going through that and being our mate, there was no way we were going to say, ‘Oh, now you’re a poof, go and kill yourself.’ It took a bit of getting used to but he’s still our mate. It was as much a matter of him getting used to us getting used to him. But we put it in the same shit-hanging comedy way we’ve always dealt with each other.”