Dazzling, inspiring read of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard in The New Yorker.

I’ll admit. Patagonia, the brand, doesn’t do a hell of a lot for me. The ritual use of dull browns, the lingering smell of piety, the full silhouettes suited to the fashionably retarded.

I live in the city where the climate is temperate. I don’t climb, don’t fish, use a little of the ocean close to shore and what little nature I get is from the television. Fornication, perhaps, is the closest I get to God.

And, yet, I’ve always found Yvon Chouinard, the climber and surfer who founded Patagonia, deeply interesting. One of those men whom you would’ve loved as a childhood mentor. Teach me to make tools, teach me to scale mountains, teach me to live in the wild.

Recently, writer Nick Paumgarten profiled Yvon for The New Yorker. If you didn’t know, or appreciate, Yvon before, read this and you’ll fall under his spell.

Here’s a taste.

He was first (and perhaps in his own mind remains foremost) a climber, a renowned pioneer of rock and ice routes around the world, and one of the luminaries of the great generation of American postwar outdoor adventurers. Then a blacksmith: he designed, and made by hand, a host of ingenious new climbing tools, and for a time was the leading manufacturer of climbing equipment in North America. Next, itinerant thrill-seeker: the relatively meagre proceeds from equipment sales allowed him to continue to pursue an intrepid life of risky recreation in the outdoors. (On a van trip from California to the tip of South America, in 1968, ostensibly to climb Mt. Fitz Roy, he and his mates carried a homemade flag that read “Viva Los Fun Hogs.” Chouinard told me, “People we met, hitchhikers we picked up, they asked us, ‘What does this mean, “Fun Hogs”?’ We said, ‘Puercos deportivos.’ Heh-heh. Sporting porks.”) Finally, eco-warrior: his travels and travails in supposedly wild places awakened him to their ongoing devastation, and he made it his mission, as a man selling consumer goods that he acknowledged people don’t need, to try to counteract humanity’s regrettable propensity to soil its own nest. In each of these guises, at least, he was authentically countercultural and anti-corporate, a credible advocate for a kind of lawless self-reliance and uncompromising common sense.

His childhood dream was to be a fur trapper, like his French-Canadian forebears. He was reared in Lisbon, Maine, the home town of his mother, Yvonne. School was all in French. His father, a third-grade dropout, was a journeyman laborer who at night repaired the looms at a wool mill there—a dur à cuire whom Chouinard remembers sitting at the kitchen table with a bottle of whiskey, using a pair of pliers to pull his own teeth, because he objected to the expense of dentures. “I was brought up surrounded by women,” Chouinard writes. “I have ever since preferred that accommodation.”

In January, 1946, Yvon’s older brother Gerald, stationed in San Diego, in the Navy, sent his family a box of oranges. Fresh fruit in winter: “That’s it,” Yvonne said. Citing her husband’s asthma, she insisted that the family move, that spring, to California: Burbank. Yvon, a shrimp with a girl’s name and no English, fled public school after a week and wound up at parochial school under the tutelage of nuns. He was, as he recalls, a loner and a geek, a D student who spent all his free time biking to city parks and private golf-course ponds to bait-fish and to hunt for frogs, crawdads, and rabbits. Before long, he was diving for lobster and abalone off the Malibu coast.

And this, about the company’s ethos. Not exactly anti-profit, but close.

Eventually, they went so far as to openly discourage their customers from buying their products, as in the notorious 2011 advertising campaign that read “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” It went on, “The environmental cost of everything we make is astonishing.” Manufacturing and shipping just one of the jackets in question required a hundred and thirty-five litres of water and generated nearly twenty pounds of carbon dioxide. “Don’t buy what you don’t need.” (Some people at Patagonia had been considering declaring Black Friday a “no-buy day,” to make their point about consumption.)

Guilt and high principle mutate into marketing: this was the Patagonia feedback loop, on high screech. To some, the slogan sounded an awful lot like “Buy this jacket, not that other one, from the North Face.” One plausible response was “Don’t worry, I won’t. I can’t afford it.” Chouinard may walk the walk, as far as not buying things—his own Patagonia gear tends to date back to the last century—but his customers are often the kinds of people who can afford as many jackets as they want. The credo “One Percent for the Planet” can misread. There are class implications, problems of privilege and access, the lingering taint of monikers like Fratagonia and Patagucci.

One catalogue, in the nineties, had a little chart of what Patagonia was versus what it was not: Fly fishing, not bass fishing. Long-haul trucking, not delivery-men. Surfing, not waterskiing. Upland bird hunting, not deer hunting. Gardeners, not survivalists. Patagonia’s people were the West’s recolonizers, the next wave of pioneers, the self-appointed protectors asserting a blue-state ethos in red-state territory—tree huggers pitching their tents in a logging camp. By now, this war for the West is a tired one, but it is in some ways a microcosm of the greater global battle between those who want to preserve lands and conserve resources and those who would prefer to exploit them.

The Patagonia catalogue can induce awe and envy. Authentic as its photographic subjects are—“We were the first to use real people, and captions saying who and where they were,” Chouinard said—it is a classic kind of aspirational branding. The life style, to a large swath, is unaffordable, if not in pure monetary terms (outdoor adventure is not in itself expensive, necessarily, although the clothing for sale certainly is), then at least in terms of time, talent, energy, and gumption. It isn’t really a lack of funds that prevents most of us from spending half the year sleeping in vans and dodging the park rangers to free-solo the big walls at Yosemite.

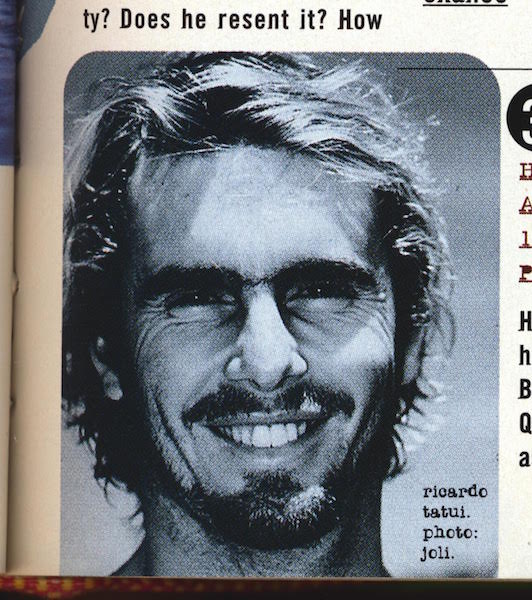

In its presentation of hale young adventure athletes, living righteously in Edenic locales, all of them with just the right amount of dishevelment and duct tape, the catalogue can emanate the passive-aggressive piety of a food-co-op scolding. It unwittingly celebrates a kind of countercultural conformity. This neo-Rockwellian idyll of desert-dawn yoga sessions, usefully toned arms and abs, spectacularly perilous bivouacs and bouldering slabs, hardy kids and sporty hounds can feel like a rebuke if you are on a sofa in the city.

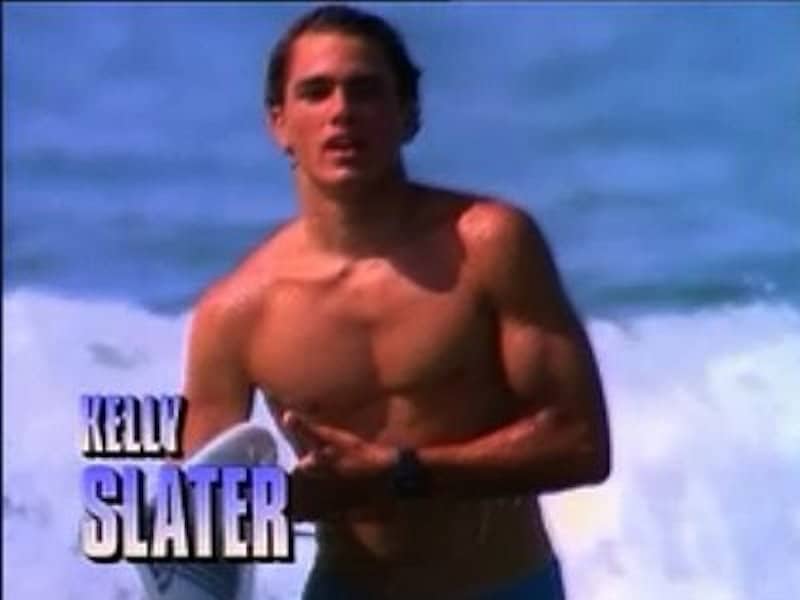

And here, below, watch the wonderful full-length movie 180 South, as climber Jeff Johnson recreates Yvon and Doug Tompkins wild 1968 trip to Patagonia.