Does a man’s pursuit of passion, even if vicariously through his children, constitute success or failure?

A scene, a snapshot, a perspective…

Praia da Consolação, Portugal, October 2010. The southern end of the stretch of sand that hosts Supertubos.

A young man sits in a rental car, a silver Opel Corsa with passenger seat tilted all the way back and surfboard wedged into the footwell.

He’s been watching the marginal, scattered windswell, unconvinced it’s worth getting in, despite the approaching midday heat. The pleasant waft of lunchtime barbequed sardines drifts through cobblestone streets behind the breakwater and makes him think there might be more value in appeasing his girlfriend by going back to the apartment for some lunch.

His swithering is interrupted by the rear end of another rental car, a Renault Kangoo, swinging abruptly into the spot in front of him. The rear brake lights have barely stopped glowing when all doors erupt simultaneously in a flurry of neoprene and joy.

A tall, sinewy man with skin like fine leather strides round to the rear of the Kangoo to release the boot and the jumble of surfboards within.

It’s a family race to the water. Girls and boys, a cacophony of stoke exploding towards the beach.

Arms and shoulders swing in ad hoc stretches as they hurry to the water’s edge. There are some brief lunges, combined with strapping on leashes.

The younger boy, darker than his brother, sprints and throws his board down like a skimboard, gliding for a second before popping a 180 off the incoming wash.

It’s all whoops and smiles. The enthusiasm is palpable.

The young man in the rental car looks on in admiration. He is witnessing the Wright family. He recognises Owen, here to compete in the WCT event and on his way to a seventh overall finish and Rookie of The Year honours by season end.

He admires the sheer physicality of the family, with their deeply earned tans and their lithe power.

He admires their joy as they swarm over the windswell, hooting each other in and throwing flyaway airs into the whitewash.

Children and parents united by a clear passion for surfing.

He is thinking: there’s a thing to aspire to. A family working and playing together. A family of supreme health and fitness, revelling in nature, culture and international travel.

Together. Happy. Surfing.

Still nearly a decade away from children of his own, the young man knows that he has seen the ideal. Later he will tell his girlfriend about it and they will dream about the future.

Fast forward eleven years.

The Wright family has faced challenges. But weigh this against world titles, big contracts, experience, travel, objective successes…

Would it be unreasonable to perceive that the joy observed in this earlier snapshot had led to some happiness and accomplishment?

Apparently so.

The title of the recent ESPN profile piece “How world champion Tyler Wright came back from a crippling virus to change surfing forever” is not only a little unwieldy, but emphasises a clear narrative.

Because don’t we just love a hero’s journey?

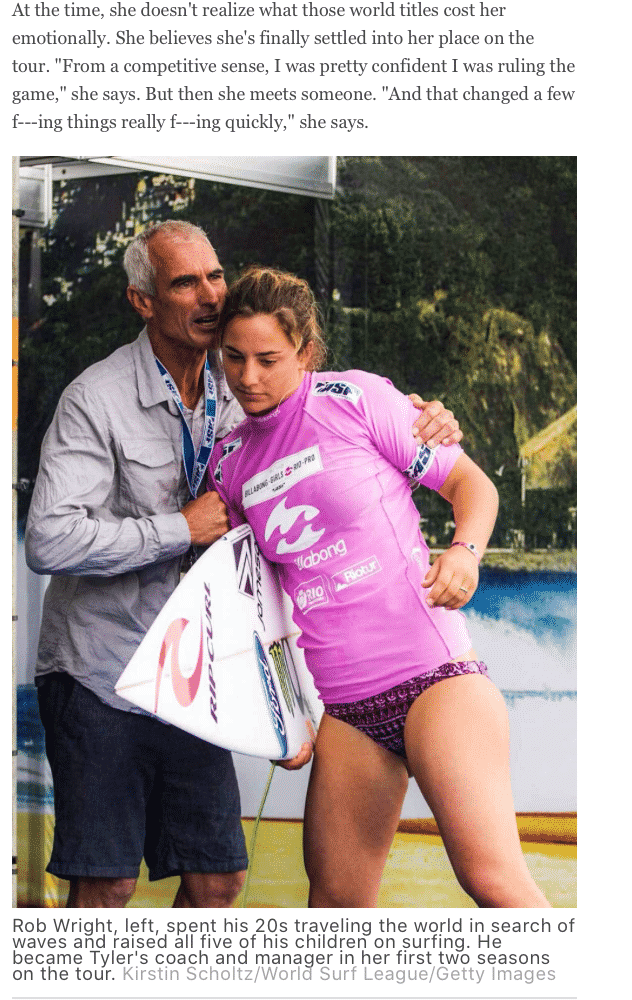

Every hero needs a villain. The villains of the piece are pro surfing and Tyler’s father, Rob Wright.

In summary…

Tyler is presented as a lost soul, forced to surf, railroaded into a career as a professional surfer by a cruel father and lacking the voice, even the “language”, to speak out against it.

She’d rather be in school.

She’s angry, but not allowed to show it.

All the men on Tour demean and degrade women.

She’s “sexualised and scrutinised by fans, sponsors and the sport’s leaders”.

We are presented, once again, with the “women-forced-to-surf-like-men” trope. (No mention of Stephanie Gilmore’s seven world titles or universally celebrated style). This is backed up by Sal Masekela, so that makes it unequivocal.

One villain is vanquished when she tells her dad she doesn’t want his help anymore.

Her uncle dies, Owen has his accident at Pipe, her mum gets brain tumours, yet she wins back-to-back world titles in a toxic sport that she hates.

She did it, but she didn’t enjoy it.

She meets her girlfriend, finds her voice, wants to confront the “homophobic, racist and extremely sexist” culture of the surfing community.

Then she gets sick with a mystery illness for a year (identified in the piece ambiguously as “post viral syndrome” and sounding very much like a euphemism for “depression and anxiety”).

She gets better, reads some feminist literature and re-emerges with her old world champ form but an armoury of social justice missiles behind her.

“We can’t talk about sexism without talking about racism. They’re not separate issues.” It’s all the same to her.

She’s angry again, but now she has language.

I’m not questioning Tyler’s experience. As Longtom said in his piece: how the hell do we know otherwise? And her goals and objectives seem admirable. Far be it from me to criticise anyone standing up for social justice.

But I might tilt the lens a little.

And I might suggest that discovering language is one thing, knowing its power quite another.

Voices don’t appear overnight.

There are many, many books.

I might also speak up for what’s missing from the ESPN piece.

No other pro surfers (of any gender) are consulted. Key family members are absent. No WSL authorities are questioned, unless you count Jesse Miley-Dyer (close personal friend of Tyler Wright).

Revisionist history?

Let me imagine an alternative writerly perspective.

One might equally present this arc as belonging to someone with a quality desirable to all – the quality of resilience.

This resilience was cultivated as part of a family unit where gender was secondary to effort and performance.

(If, instead of what actually happened, young Tyler had been sent to school while the boys played in the waves, how would we view that?)

Learning came, as all good learning does, from discomfort.

A father dedicated his life to ensuring his children lived in pursuit of health and happiness, with minds broadened by travel and bank accounts furnished by companies willing to pay them for elite performance in a sport idealistic to millions but rewarding very few.

Three out of five children top-ranked professional athletes.

Does a man’s pursuit of passion, even if vicariously through his children, constitute success or failure?

One might suggest that the determination and focus fostered from a young age in a hard-knock, cut-throat sport and family dynamic was the defining factor that allowed both Tyler and Owen to emerge victorious from debilitating injuries that would have ended most athletes.

The Wright children are pro athletes forged in iron. They lead lives that need no filters to be the epitome of Insta envy.

You could say that the reason Tyler Wright is so damn good at surfing, the best in the world, no less, and the reason she has a platform and a voice, is precisely because of her upbringing.

Perspective.

And where is Rob Wright’s voice anyway?

The writer of the ESPN piece excuses the omission of Rob’s voice with an addendum to a sentence stating that he’s been diagnosed with early onset dementia.

No point in talking to him then, eh.

It’s deeply unfair to characterise him as not only the cruel and uncompromising patriarch, but almost as a symbol of the patriarchy itself.

And to use THAT picture in the article, yet snuff out his voice?

I’ve got no skin in this game, but I feel for the poor fucker.

And what about Owen’s voice?

Or Mikey’s?

One might presume that in a profile piece about a professional surfer citing a toxic family environment as reason for her struggle and unhappiness, it might be privy to obtain the views of two of her siblings who have followed the same career path.

As for Longtom, dear Steve with his Tolstoy and his Lennox lore and his goat’s balls. If you’re that close to the situation (given that they live(d) in Lennox and you clearly know them) then what about some insight beyond bunging Rob in a ute and dropping him off again? That ghost shell image is about as useless as Alyssa Roenigk’s half-sentence brush off.

Don’t just allude to things unseen. Don’t you leave meat on the bone, too.

With the ESPN piece the writer has leaned hard into the issues du jour, just as Tyler has, but it’s a well-worn narrative, and it misses enough to cast doubt on the perspective.

There’s a lot more to say about the Wright family, I’m sure.

Many perspectives.

This once-young man would like to hear the other voices.