"The wildest, craziest wave I ever caught or somehow managed to ride and survive to tell the tale."

Caracsse, tu trembles?

Tu tremblerais bien davantage, si

tu savais, oú je te méne.

(“You tremble carcass?

You would tremble a lot more if

you knew where I am taking you.”)

— Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, Le Vicomte de Turenne1

There’s big days, good days, scary days, and crazy days. And there’s days that are all that (and more) in one session, indeed one single wave can epitomize or encapsulate everything imaginable or possible in a surfing life.

For me, there’s a session that stands out in memory. Perhaps the wildest, craziest wave I ever caught or somehow managed to ride and survive to tell the tale.

It went something like this: About ten or twelve years ago (my guess is 2010 or so, late season, maybe February or March), it was big.

Not giant, but easy 15’-18’ plus and light Kona (SW) winds.

Sunset Beach was closed out and washing through from the Third Reef. The Bay was crowded and junky, kind of onshore and bumpy; not appealing at all. The outer reef down at the end of the street, on the other hand, was working and looking good. But it was overrun with jetskis and tow-teams and I couldn’t find anyone to surf with.

I was amping to surf though; and after walking down to check the surf for the third or fourth time in about an hour or so and pacing around my house and yard like a maniac, I just decided to paddle out solo. It felt obligatory, a matter of both principle and fate. I was out there no matter what.

I grabbed my trusted 11’7” pintail, threw a leash on the board, waxed up, stuck a swim fin in my shorts, and made my way down to the beach at Backyards like I had done for over half my life, it’s a short walk (about a football field in length).

Outside Kaunala was pumping. Also known as “Phantoms,” there were giant A-Frames coming out of the NNW (kind of a weird direction for Phantoms — a West or WNW is preferred), standing tall, throwing top-to-bottom, and walling up across the reef about ¾ of a mile out to sea.

It looked relatively clean — conditions are crucial (really everything) out on the Outer Reefs. Too much wind and it gets really challenging; the risk levels rise drastically with every knot and gust. It’s a thin line between love and hate (cue: Pretenders).

That day, however, light Konas groomed the peaks with offshore plumes (Ehukai) misting 50’-60’ above these Leviathans. Glorious.

And: There were no jet-skiis out there anymore for some reason. Lineup was empty. Stoke! This was my opportunity — the Fates seemed to smile upon me; and my timing was perfect (or so it seemed) . . . .

Little did I know that while I was pacing manic circles around my house in a fit of anxious anticipation, moments before there had been a giant clean-up set that washed everyone in — in fact, the photographers (Larry Haynes and Hank “Foto”) had been caught brutally inside at “Twisted Sister” (a.k.a. “Generals” — the inside corner on a wide West bowl) and impacted directly, resulting in a complete loss for Larry (his ski was demolished) and Hank had to rescue him.

Everyone else, apparently, chose to exercise caution and call it a day. Discretion is the better part of valor when it gets hairy like that.

Yet, of course, I was totally oblivious. I passed my neighbor Dylan Aoki who was sitting in the bush. He’s a fireman. He said: “Be careful out there! There was just a big set — it’s gnarly!”

I was like: “Yeah, man! Thanks.”

I didn’t really hear him — I was 100% focused on my objective: hitting the water and paddling out to the peak. In all honesty, I was wishing I had someone to paddle out with.

At the water’s edge, it did look gnarly — ominous and foreboding. I felt it in my gut. Of course, it is always best (and frankly more fun) to surf with at least one (or a few) other person(s); it’s a lot easier psychologically and seems safer, too, when I’m with another surfer.

But my wingman (Davis) wasn’t around, I think he had moved back to the mainland at that point. So, I was on my own. Truth is: you’re on your own out there anyway. There’s really not much anyone else can do for you if and when shit gets real. That’s the bottom line in Big Water a mile out in the ocean. Solo mio.

The rip was roaring — the first real indicator of what’s happening and what could (and probably will) happen. Torrents of water moving fast and strong, chops were easy 6’-8’ and I got pulled out there in a raging slipstream, like Class V white-water rapid, lickety-split.

I made sure to give “Twisted Sister” (a.k.a. “Generals”) a wide berth, as that’s a zone one can easily get caught inside and destroyed (e.g., Larry Haynes). In big surf — whether it’s Sunset Beach, Waimea Bay, or the Outer Reefs — the paddle out alone is as thrilling, challenging, and dangerous as anything else one will encounter.

And it takes a solid strategy, follow-through, and execution to make it out unscathed. It’s the first test. You gotta be loose, move with the water, alert and aware: it’s a process of give and take — “like a Willow Tree,” Roger Erickson told me once (they bend, don’t break in the wind). My mind was racing with exhilaration and the proverbial “butterflies” were fluttering Big Time!

I just knew viscerally by how fast I was moving (getting sucked out in the roaring rip) and by how the water was looking and feeling (so much power and energy popping all around) that this was going to be full-on.

As I passed “Twisted Sister” a set unloaded and went square — top-to-bottom — and spit hard like a massive cannon-shot. I thought out loud: “It’s big, man. Bigger than it looked from the beach!” Again, I secretly wished I had a partner . . .

I paddled way outside. The state of the ocean was just breathtaking. Truly awesome. The grand expanse of the Phantoms lineup is spellbinding: dozens of acres of water (almost a square mile I’d estimate) of raw, wild ocean, raging rips tearing in and around mountainous peaks and walls and gaping, spitting barrels that would consume a Greyhound Bus.

From where I sat, I couldn’t even see the beach anymore. It took everything I had to get a sense of things, get my bearings and orientation. I was way the fuck out there on the Northernmost corner of the North Shore (then as now, it never ceases to amaze me) — almost a mile — “a Norway mile” as old seamen say — all alone, observing the backs of 15’-18’-plus waves (30’ – 40’ faces) breaking at outside, Third Reef Backyards running all the way to Sunset (to the West); as giant freight-trains could be seen stacking from Outside “Revelations” (to the Northeast) walling up across the Phantoms reef — the “channel” was gone. There was no Revelations channel.

“That’s unusual,” I thought.

The swell direction was super steep out of the North-Northwest, also unusual. From where I was sitting on the far outside at the “top” of the reef (wherefrom I could see Haleiwa to my left and Turtle Bay to my right, and the big white golf-ball satellites above Kawela: what we call “Epcot Center” — that’s when/where seasoned Phantoms surfers know it’s big and you’re on the outermost reef: lineups don’t lie) it looked like the channel between Phantomsand Backyards was also closing out!

That’s CRAZY because the Kaunala drainage is the deepest natural channel (a submarine canyon) on the entire North Shore (easy 60’-80’ deep). Not a good sign. On top of that, there were multiple whirlpools of water sucking and twisting in ways I had never seen before (or since). The waves were BIG. Easy 20’.

I thought of Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Descent Into The Malestrom”:

The collision of waves rising and falling, at flux and reflux . . . in

the immediate vicinity of the vortex . . . I felt a sickening sweep

of descent . . . Never shall I forget the sensations of awe, horror,

and admiration with which I gazed about me . . . . Here the vast

bed of waters, seamed and scarred into a thousand conflicting

channels, burst suddenly into phrensied convulsion-heaving, boiling,

hissing-gyrating in gigantic and innumerable vortices, and all whirling

and plunging on to the eastward with a rapidity which water never elsewhere assumes

except in precipitous descents . . . 4

In all my years in the ocean, I have never seen anything like it — “the prodigious suction” — with my own eyes. And I was scared. No question: I was in way over my head.

“I should not be out here,” I said out loud.

This kind of empty, lonely, undeniable, and inescapable feeling of despair. One can’t indulge it for long otherwise one paralyzes. I don’t often get or feel like this in the ocean (I don’t like being scared and typically I manage or overcome fear with the healthy diversion of fascination and focus — “pure will-less knowing” as Schopenhauer puts it re: “the sublime”); but I didn’t have the time or luxury for such philosophical indulgence since I was terrified and, furthermore, because I understood the severe gravity of the situation and moment. “Happiness and unhappiness have disappeared,” sez Schopenhauer, “we are no longer individual; the individual is forgotten; we are only pure subject of knowledge; we are only that one eye of the world which looks out from all knowing creatures, but which man alone can become perfectly free from the service of will . . . neither joy nor grieving is carried with us beyond that boundary.”

In other words: Think. Get a plan of action. Pronto!

There’s no swimming in when it’s like this, no way.

Get caught inside? Certain you lose the board (no question); and doesn’t really matter anyway since you’ll probably drown if you do get caught at impact by a wave that’s 50’ plus on the face buried under many tons of water in the dark abyss of “Davy Jones’ Locker.”

This was years before so-called “flotation” and inflatable vests and all that, by the way. There’s no paddling in either at this stage: no possible way anyone can paddle against that rip (pulling seaward at 8 to 10 knots easy); and even if you could, there’s a very strong possibility of getting caught inside and losing the boards and/or drowning. No thanks.

All I was thinking was: “Get the fuck out of here!” But how? . . . The only way in is to catch a wave. A set wave.

At that moment, the horizon shifted on the Revelations side (Northeast), which, again, is extremely unusual as the standard indicators are rather more on the Western horizon coming from the Sunset or Haleiwa side (on the proverbial “West Finger Reef” according to the old-timer Pioneers of this reef: Flippy Hoffman, Steve Bigler, Mike Taylor, and Roger Erickson preeminent among them — I’ve surfed with them all); not at this moment, however. Every atom of my being was intensely focused. On survival.

A set was coming — INCOMING! These giant blue Leviathans marched toward me at 60 mph (or faster) and all I could do was paddle as hard and fast as I could to meet them and hopefully — Dear God! — not get caught inside.

. . . but in the next moment I cursed myself for being so great a fool

as to dream of hope at all . . . 7

It’s so true: There are no atheists in the impact zone! But caught inside it looked like I was going to be as I stroked vertically up the face of the first wave that was already feathering and beginning to throw. I just barely got over the top of the first one and free-fell airborne over the back (which is super hairy as the impact of the board can knock the wind out of you, bust your jaw, or just plain knock you out — I’ve gotten stitches in my chin twice (16 total) from the impact of this kind of thing before) and slapped down without missing a stroke. I was horrified by what I saw before me in the airborne instant coming over the crest of that Behemoth: at least 10 more waves stacking, each bigger than the one before it. I was doomed.

But the intelligence of the body (i.e., instinct) overrode my desperate pathetic mind and did what only it could do: paddle like a demon. Again, I found myself crawling, pulling with everything I had vertically up the face of a wave (Eight? Ten strokes?) that was easily five or more board-lengths tall — a veritable drive-in movie screen, bigger than a telephone pole or coconut tree and feathering for what seemed like a mile — “a Norway mile” — in either direction.

At that instant, a little voice said: “You can catch this wave.” In that nanosecond, I recognized that not only could (must!) I catch this wave; but if I didn’t, I would most certainly be caught by the next one (or the next one, etc.). I was already anaerobic (totally winded and running out of oxygen), so I whipped it and . . .

Caught the wave. A miracle in and of itself! I was right on a little ledge (some call it a “chip”) that gave me a rather smooth easy entry. I was up and in a low crouch — then the wave jacked and flared and I went vertical over the ledge: straight down. I sort of plowed into and through another ledge as the wave jacked even harder and at that moment my board disconnected and I was in a full on fin-out freefall for probably a board length (11’ or 12’).

And I’m free, free fallin’

Yeah I’m free, free fallin’

Free fallin’, now I’m free fallin’

Now I’m

Free fallin’, now I’m free fallin’

I wanna glide down over Mulholland

I wanna write her name in the sky

I’m gonna free fall out into nothin’

Gonna leave this world for a while — Tom Petty

I landed and reconnected relatively smoothly without losing any momentum. The voice spoke again: “There’s no going right or left. Just make the drop!” This was a drop that seemed to never end; I might have even disconnected and got airborne again, I’m not sure. It was straight up and down; and an experience in aquadynamic physics like I’ve never had before or since.

The wave was sucking out so hard that it took me a few seconds to get down in the trough (the proverbial “pit”) whereupon I knew the whole thing was going to close-out and probably destroy me. I was at full hull-speed (45 mph, maybe faster, combined or compounded by the mass and the velocity of the wave itself I might as well have been moving at 75 or 80 mph, do the math someone please) as fast as one can go on a surfboard that’s for sure.

My peripheral vision told me that what seemed like the entire Universe was closing out all around me. I prepared for the worst.

Utterly consumed. Engulfed by an explosion of cascades of whitewater, a literal avalanche, yet, somehow, I was still on my feet. Immediately I leapt down prone on my belly and grabbed the rails and got ready for the whitewater adventure. Then the second explosion blasted like a Hydrogen Bomb detonating — blowing me and my board into the air (still consumed by mountains of whitewater); at one point I even lost hold/grip of the board and then again (somehow) reconnected and landed only to be blown out in front of the closed-out deluge.

Instantaneously, I jumped up to my feet and found myself coming over a massive double-up as the wave reformed (as it moved into another section of reef) and transformed from a mass of whitewater into a titanic wall of blue (easy 40’ plus on the face) that stretched before me into Eternity.

It was beautiful, sublime — I was surfing! And it was fun!

Flying at Mach 2 in full forward trim across the highline, I assumed I had made the transition from the Outside Reef to the middle section (what we call “Outer Freddies” — outside the surfspot “Freddyland” which sits several hundred yards inside Phantoms in the middle of Kaunala Bay).

This is where the waves often reform into these long, drawn-out walls that will have a couple/few hollow sections that can be as challenging as they are thrilling to negotiate.

But this aquatic transformation wasn’t Outer Freddies — unbelievably (and I didn’t know it yet at the time) I was streaking across the outside section (what they call “Chevrons” because one can see the Chevron Gas Station down at Kammieland from this spot) of Backyards itself — which means (for those who know or care) that I had taken off at Phantoms and miraculously (against most all odds) blasted across the channel (which simply doesn’t happen!) to Backyards . . . Insane.

But, as I said, I didn’t know what was really happening yet. At this point my fear and anxiety had metamorphosized into PURE STOKE as I strobed across a giant, perfect, blue wall that stretched into the horizon.

In the approaching distance, I saw a big Left coming (a spinning barrel) toward me, throwing top-to-bottom, so I prepared to prone out and dropped to the bottom of the wave and got low in anticipation of another, final close-out, with an eye for the shore where I aimed for the beach.

I felt the water getting shallower; could see the reef whizzing by beneath me. Where and when I caught the wave (which seemed like a lifetime ago at the point — a million miles behind and away from me) was probably 60’ deep (or deeper); now I was in water maybe 15’ deep and getting much shallower very quickly. There was a torrential side-shore rip running at this stage, which is normal when conditions are like this since all the water pushed in by the big surf has to escape back out to sea. When the wave closed out (again) I laid back down prone on my board just to play it safe — I was going to the beach!

As the whitewater backed off a little, I stood up again for a final time and directed myself toward shore. As I did so, I looked at all the houses (which I assumed were at Velzyland, a.k.a. “V-Land”) and thought to myself: “Boy, they sure have built-up and developed V-Land!” (V-Land used to be the North Shore “ghetto” — low rent, dilapidated houses, but in the ensuing decades it’s become gentrified, transformed into a bunch of trophy houses (mostly empty boxes) for the rich and famous: e.g., Sean Penn, Eddie Vedder, et al.)

But it wasn’t V-Land I was looking at — it was Sunset Point! (Nearly a mile — “a Norway mile” down the coast.) I almost fell off my board in shock! At that moment, I realized what had just occurred: I had ridden a wave from Phantoms, across Backyards, all the way to Sunset, where I was proning in at the “Boneyard” right in front of the old drainage pipe (it’s gone now). Beyond incredible — IMPOSSIBLE!

As the aerial photo above indicates, Sunset Beach (or Paumalu) and Phantoms (Kaunala) are two distinct drainage and reef systems separated and clearly divided by a huge channel (the deepest on the North Shore) and a headland (known as Backyards and/or “Sunset Point” — where I live).

In other words, there’s not only at least two channels (the one separating Phantoms and Backyards and another separating Backyards and Sunset) which are the result of freshwater rivers (Wai) draining out from the Koolau Mountains: headwaters of both Kaunala and Paumalu streams, as well as an entire surfbreak (Backyards) that actually consists of at least three different, distinct sections.

Moreover, given that I caught this wave about a mile — “a Norway mile” — out to sea (from the beach/shoreline) and that I also covered a distance of approximately another half mile (or more) — like 6 or ten football fields) between Phantoms and the Boneyard as Sunset, I rode for something like a mile and a half (or more) on one wave in less than a minute. Truth.

Again, someone please do the math here, I’m not that good at physics (at least not when it comes to the numbers); but it seems to me I was moving pretty fast — and far. I was dumbfounded as I steered to shore and stepped off my board on to the sand. I can’t tell you how good that felt.

There were two guys walking with their guns (both Fire Engine Red Owl Chapman single fin pintails not unlike my board — although mine is kind of a custard yellow and a little longer): Kalani Chapman (Owl’s nephew) and Christian Lewis. They were longtime roommates, living at that time on the Point. And they were headed down the beach to paddle at Phantoms.

They stared at me incredulously and asked: “What were you doing out at Sunset!?!” Mind you, Sunset Beach was totally closed out and washing through from Oblivion way, way outside.

I said: “I wasn’t surfing Sunset. I just caught a wave at Phantoms and washed down here . . .”

I barely got the words out, knowing how ridiculous —how IMPOSSIBLE — what I just said sounded. These are both veteran big wave riders. Kalani (a pro surfer and Pipeline Master) was born and raised (literally) on the sand where we stood. He looked at me like I was crazy; but he and Christian also know me well enough to know that I can surf, too, and maybe (just maybe) I wasn’t bullshitting them.

We walked together back up the beach. It took a while. The profound sense of relief I was experiencing mixed with what the shrinks would surely call the onset of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Like surviving a plane crash, a nuclear blast, an avalanche, or a bear attack or something very extreme and deadly, I was in disbelief but also subconsciously and slowly coming into a clearer consciousness, acutely aware of the severity, gravity, and unbelievable luck of everything I had just experienced.

As we made our way past the stone walls fronting the beachfront houses at Backyards, we noticed the detritus (flotsam and jetsam) of the remains of Larry Haynes’ jet ski littering the shoreline. It had been totally destroyed: pieces and scraps of it everywhere, evidence of what had happened less than an hour prior.

Rounding the corner, as the beach rises and transitions into Kaunala Bay, we could see Phantoms breaking a mile out to sea. It looked treacherous. Those guys looked at me like: “You were out there?!” I honestly couldn’t believe it myself. It looked dangerous, death defying really, and not at all inviting (suffice to say: they didn’t paddle out). And when we got to the spot where I had paddled out, there was Dylan (the fireman) in more or less the same spot I last saw him — a veritable lifetime ago for me it seemed.

He looked at me like I was a ghost. Which, in a manner of speaking, I guess I was (or should have been). He said something like: “What happened to you? I saw you paddle out and then you just disappeared. I thought you might have drowned!”

Once more, I attempted in vain to describe (I couldn’t explain) what had just happened. I don’t think he believed me or it didn’t register or something — it was IMPOSSIBLE. But it happened. I know I paddled out. Dylan saw me. And I know something happened more or less as I describe herein (in that I caught a wave way outside Phantoms and came in at Sunset Beach at the Boneyard after riding — surviving — that wave). Yet it all seemed beyond the realm of possibility.

I was tired. Exhausted. Totally drained and feeling this weird kind of dissociation from myself and surroundings. I wanted to sleep, take a long nap. So, after a warm shower and maybe something to eat or drink, I lay down on my bed and crashed.

A couple hours later, now early evening, I awoke. Startled. I shot up with the full recognition and comprehension that I was extremely fortunate (yes: Lucky) to have survived what I simply shouldn’t have. I was in utter disbelief with the realization of the extremity of the circumstance. Nothing a beer or two won’t cure! After which I had some dinner and gave my shaper, Owl, a call.

I told him what happened as best I could. Owl listened and then declared: “I’ve done that.” It was actually very reassuring to hear him say that. It meant that it could happen! It was possible after all. I wasn’t crazy. Owl did it too. But I learned in the next sentence, he did it on a windsurfer — in 25’ surf by himself, he told me. That’s a little (maybe a lot) different because he had wind power and a harness and boom to hold to assist or facilitate covering such a Grand Expanse of water. Nevertheless, he did it and he explained to me how it probably happened.

As noted, the swell that day was extremely North (a North-North-West) which means the surf was coming from the other (really the opposite) side of the reef from where the waves typically arrive (West). The swell was on the rise — rapidly — and the tide was also on the rise: flooding. Given that the reservoir of water for the North Shore extending from Revelations to Waimea is contained in that deep trench I mentioned (super deep, like a lake one might say), when the tide is flooding (or rising to High Tide) all the water moves from Northeast to West, literally spilling out of a proverbial bowl downhill; likewise, an ebbing (lowtide) pulls in the opposite direction, filling the bowl back up again.

Thus, what probably happened was that I paddled out and caught (or, more properly stated: was caught) by the High Tide Set of a peaking swell combined with the flood of the high tide slipstream/rip where everything (all the ocean forces) pushed across from East to West. A rare — once in a lifetime — but plausible scenario. Not only could it be done (I guess) in theory, it was (at least twice: by Owl and me).

So it goes. Believe it or not, but it’s all true.

And I concede that to this day — this moment as I type these words — I am haunted by the memory of my experience. My blood runs cold every time I think about it.

For years afterwards, I would have dreams (a kind of ominous, foreboding nightmare) of everything that could (should?) have gone wrong: had I been caught inside by that set; had I not made the drop; had I been blown off my board (etc., etc.) — I would most certainly been lost at sea given the overwhelming forces of nature that afternoon.

I don’t think for a second that I would have been able to swim through those waves, the surf zone, and rips. I would have either been buried and drowned almost immediately or sucked out to sea.

And given the fact that Dylan lost sight of me almost immediately (and he was watching me) and that there were no jetskis in the water, I was on my own. No one would have rescued me. I could have easily just disappeared . . .

One inference that can be drawn from this tale is that my board saved my life. No doubt about that. It’s interesting to note that, over the years, Owl often remarked in the shaping room as he hand-crafted my guns: “Kid, this thing’s gonna save your life one day.” Fuck’n A Right, Owl.

Mahalo Nui Loa!

But the moral of the story, I suppose, is to be more careful and exercise discretion. Be prepared for the worst. This realization is hardly a revelation. But it’s an essential one. Know your limits. Study the conditions very carefully, think twice (or more), and err on the side of caution.

I was 40 years old (or so) when this happened. I wasn’t a stupid, reckless kid. I was and remain a big-wave rider with decades of experience at this break (literally my Backyard) where I have surfed, swam, paddled, sailed, and dove for 30 years. But I won’t make that mistake again.

I’ve seen people disappear out there. Jim Broach in 1993, for example, paddled out on a big windy day never to be seen again. No body. No board. Nothing. Gone.

The guys he paddled out with — Boogs Van Der Polder and Rusty Moran, a couple intrepid Australians and two of the better big-wave riders at the time — barely survived themselves (they never even caught a wave; they just got mercilessly caught inside) and when they came in, they packed their bags and split.

I never saw (or even heard about) them again.

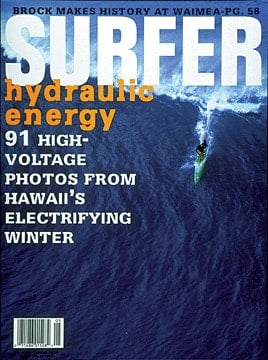

(SEE: Surfer Mag cover shot of Boogs at Phantoms above.) I know other surfers — surfers better than me — whom I respect and admire that have sworn off Phantoms after enduring near-drowning experiences out there. One guy, a Hawaiian, told me: “I promised to God that if he let me live I’d never paddle out there again.” And he never has.

Editor’s note: Subscribe to Andy St Onge’s Substack here. It’s wrapped in wild North Shore stories.