It was hard to ignore how far ahead in the rankings Carissa Moore started the day and how much she lost by the end of it.

You have one shot and one opportunity.

There is always something compelling when an athlete shows up, really shows up, and does it on the day. All or nothing, for all the marbles.

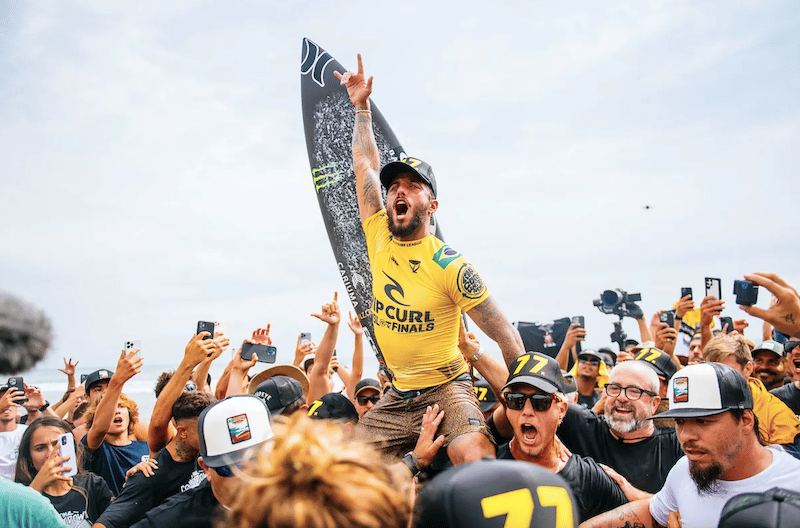

On Thursday that’s exactly what Steph did to win her eighth world title. Making a run from the bottom of the draw straight through to the top, she used her trademark style sharpened with a progressive edge to win on the rights that suit her so well.

It should be a fairy tale story.

From fifth to first, after a rollercoaster season with more troughs than highs, Steph won the title. She also broke the record for women’s world title count that’s stood since 2006. Onshore winds turned the waves to shit, but Steph kept rolling. She only needed two heats to beat six-time world champion Carissa Moore. Steph once said that she expected to Carissa to be the next Kelly. Who’s chasing Kelly now?

But even as Steph wrote a dramatic sports story and celebrated her success, she acknowledged the long strange ride she took to get there. Steph started her season by missing Pipeline due to a positive Covid test. She bobbled at Sunset, where she has won in the past, and scraped into the final five, still several time zones from the rankings lead. This wasn’t supposed to be her year — until it was.

Carissa is the rightful world champion, Steph said from the podium with characteristic grace. It was hard to ignore how far ahead in the rankings Carissa started the day and how much she lost by the end of it. I doubt Carissa especially liked being reminded that she should have won. Surely that felt like salt in the wounds.

It wasn’t Carissa’s best year. She told me at the beginning of the year that she didn’t get her usual time off because of Olympics obligations. She came into the season more tired than usual. Still, she was far and away the rankings leader by year end. After winning the one-day final at Trestles last year, she knows how to do this event. But not this year, not this time.

So, what do we make of this year’s format changes?

In her post-heat comments and later on Instagram, Johanne Defay was forthright about her dislike for the one-day final.

“Surfing as a sport is not an exact science,” she says on Instagram. “That 35 minutes in the water did not reflect my year or the competitor and surfer that I am.” It felt to her as though her whole season was lost in a single 30-minute heat. Finishing third in the world, of course, is hardly nothing.

Steph says it’s time to change the system. Presumably she means an end to the one-day final. If there’s anyone in position to change how the tour works on the women’s side, it’s Steph. Over time, she has quietly done just that, most notably in pushing for better conditions during the women’s heats.

And Steph is right.

While a one-day championship works for many sports, the sheer randomness of the ocean rules against it. Do we get the same results — mens or womens — if the conditions had stayed clean or the waves had been bigger?

Maybe, maybe not.

And it’s hard to argue that Trestles is the measure of what World Tour surfing should be. The year-long world title race mediates the judges’ weird quirks and the ocean’s wild ideas.

While Steph is changing the system, the mid-year cut also needs a rethink. A twelve-woman draw is a joke from a sports league that makes a lot of noise about equality. Prize money equity only goes so far when there are so few seats at the table. And, surely a heat draw where a win in round one sends surfers straight to the quarters doesn’t make a hell of a lot of sense. The cut and reduced draw should have raised the stakes; instead it highlighted how arbitrary a judged sport in ever-changing conditions can be.

What the mid-season cut and the one-day final have in common is a brutal finality.

Certainly, the point of competitive sport is to distinguish between winning and losing. There’s no sugar-coating that reality. But in the context of surfing, where so many variables fan out beyond the competitors’ control, the results felt almost arbitrary. The waves could stop. The judges could lose their minds. Oh hey, look, you’re out.

In creating both the cut and one-day final, the WSL has confused cruelty with drama. They’ve assumed that their audience — that’s us — wants to see dreams crushed rather than fulfilled. And it’s true, sometimes we do. Sometimes we’re assholes, and we watch heats to see someone lose.

But didn’t Margaret River feel the opposite of fun, as one after another, surfers got sent home? It didn’t feel like the kind of drama I look for in sports. It felt contrived and artificial, drama for drama’s sake.

So many of the younger generation of women — the women who are most likely to change the sport and push it into the future — were sent home at mid-year. Only Gabriela Bryan from the rookie class survived. It felt like a step backward rather than forward for women’s surfing.

At the end of the day, Steph won this one and it’s impossible to hate the idea of Steph holding the record of most world titles. Her contribution to women’s surfing is undisputed and her surfing in right points is unmatched. Who wouldn’t want to be able to surf J-Bay like Steph?

For her part, Carissa has all the pieces she needs to chase down Steph’s new record, if she wants it.

Carissa remains the most complete surfer in the women’s sport.

She has said she wants to improve her backside barrel riding, and there’s signs she’s starting to do it.

Now’s the time, Carissa. Go get it.