"Great sense of humor to go along with those big sad Buster Keaton eyes."

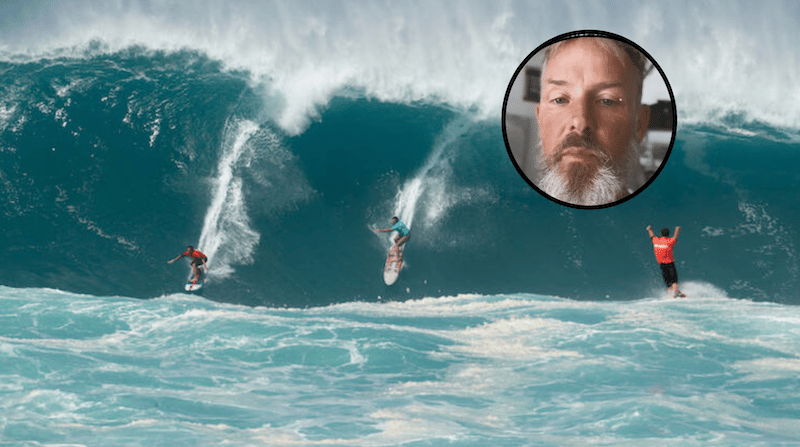

News just in that the Californian shaper Pat Curren, a big-wave pioneer on the North Shore, and daddy to three-time world champ Tom, has died after a long illness.

A couple of years back, Pat was living in the carpark at Swamis with his wife and special needs kid, drowning in poverty as Paul Schmidt, a shaper from Rockaway Beach in New York, described it.

Schmidt’s story of meeting Pat post-surf will jerk a few tears out of anyone who knows the legend of Curren.

This past January, I hopped on a flight for a quick trip to California. A few friends and I rented a Westfalia and spent two weeks surfing and camping in San Diego. Luckily, a swell had arrived on the last morning of the trip; I paddled out at Swami’s, caught a few fun ones, and then ascended the long flight of stairs back to the parking lot.

As I made my way to the top, a woman approached me and asked if I had built the board I was holding. She said she could tell just by the way I was holding it. The enthusiasm with which she addressed the work far surpassed what I would call the ‘usual intrigue’ of a passerby. We chatted for a bit and, as she walked away, I thought I heard her say, “You should bring the board over to our car. My husband, Pat Curren, is in it and he would love to take a look…”

I must have mistaken her, I thought. I actually began to walk back to the van as I reheard what she had said in my head. Then I stopped, turned around and looked across the lot. There, in the front seat of a Tahoe, was an old man, with a white beard and a matted, thick head of hair.

I made my way over to the car slowly and in, I’ll admit, a certain degree of disbelief. Of course I was well aware of Pat Curren’s name, his beautiful gun shapes and legendary first-day-out at Waimea story, but otherwise, I knew nothing of what he had been up to in his later years.

An 87-year-old Pat Curren stepped from the car, and we shook hands. He was characteristically quiet, and carried himself with an utterly distinct and captivating blend of dignity and humility.

For the next three hours, we looked over the boards I had brought with me, talked tools, travel stories, and his early years of board building with Velzy. I realized at some point that I was dehydrated and a bit dizzy, standing there baking in the sun, still wearing my wetsuit. That’s what happens when you get caught up in the magic joy of chance encounters with people you look up to.

Pat’s wife, Mary, and I exchanged numbers and have stayed in touch over the past 7 months. Over long and frequent phone conversations, I’ve learned about their lives and struggles. As I’ve grown to better understand the depth of Pat’s indomitable spirit and determination to continue building boards, regardless of age, multiple near death experiences over the past year, a pandemic, lack of proper space and materials and finances, the effect has been both inspiring and difficult to accept.

Most days, weather and health permitting, he works on a template outside their small trailer, in the open air. I even caught wind that he may have been doing a bit of shaping out there too, despite having no shaping bay to work in. When I learned of this, I instantly called some friends in the SoCal area to try to find him some space. That’s what you call youthful optimism and maybe even a naive eagerness to fix a problem without fully grasping the intricacies of a unique situation. It just isn’t that easy.

There isn’t enough room for Mary to sleep in the trailer with their special needs daughter and Pat, so she’s been making her bed in the back of the Tahoe for the past year. They have no private bathroom. Mary receives food from local food banks when possible. Pat has been in urgent need of dental surgery for the past 6 months, which they cannot afford. They are at risk of losing what little they have left, including their trailer.

There may be a tendency to think someone else is sure to help out, so I don’t need to. While avoiding the uncomfortable realities standing before us in plain sight, a family slowly drowns in poverty, just down the street from multimillion dollar, beachfront homes and organic supermarkets.

I am well aware of how hard it is for Pat and Mary to allow me to share some of their current situation – she’s been stoically resistant to offers of help for over 7 months now. Most of my ideas were small fixes; another potential customer for Pat, an extra set of hands for an afternoon, thoughts and prayers. I’ve seen and heard how Mary and the family have supported him as best they can, but this family is weary.

Pride can be a beautiful thing. The pride Pat has taken in his work which bears his name is evident to even those far outside the surf world. But when we are in moments of dire need, when we’ve exhausted all viable options on our own, it is through simple acts of honest vulnerability that we can open ourselves to the inherent kindness in each human being’s heart.

Today, August 9th, Pat turns 88 years old. We have an opportunity to lift up and support someone who has devoted his entire life to being the very thing others have commodified, and packaged, and sold, and made millions feeding to the surf-hungry masses.

While most of the surf world went the way of carbon copy machine cuts and overseas production outsourcing, Pat chose to do it his way. He has stood as a guiding light for the younger generation of by-hand board builders, of which I find myself a part, for 70 years. 70 years and hardly a penny to show for it.

Mary told me once, “What people don’t understand about Pat is that he would give somebody the shirt right off his back with no idea if he’d get another one.”

Paul set up a GoFundMe with a hundred k goal and even created a limited edition tee for donors.

“You can help raise funds to get a more permanent roof over their heads, room for them to breathe and get some much needed rest, health care, food, and space for Pat to work,” wrote Schmidt.

A common theme among comments on IG was, why aren’t his kids Tom and Joe helping the old man out, which launched an online battleground drawing in various family members of the Curren family, including Joe and Pat’s grandson Nathan.

Anyway, Pat got some cash and for this he was eternally grateful.

“Just beyond what I expected,” said Pat.

A few years back, historian Matt Warshaw wrote,

“The camera loves Pat in a way that it loves few others in the sport, and he was good enough to occasionally play along with the filmmakers. Great sense of humor to go along with those big sad Buster Keaton eyes. Tom’s the same. I have a thing for beautiful damaged surfers, and the Currens to me have always felt like a two-for-one deal.”

RIP.