It ain't pretty reading, but maybe a lesson in there somewhere…

Last November, you’ll remember, two Australian surfers were murdered during a surf run through Mexico.

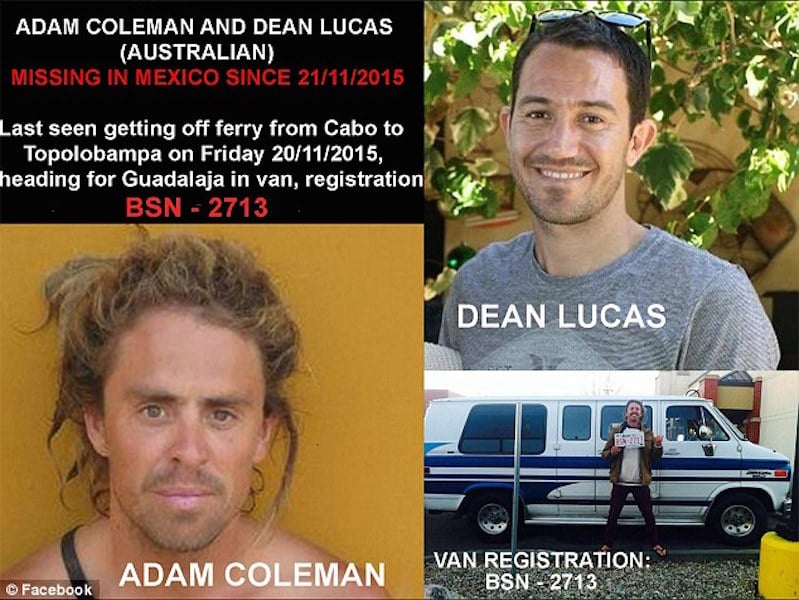

It’s hardly a secret that the government v drug cartels civil war makes parts of Mex places you don’t want to go near. Two Australian surfers, Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman, had a swing driving through the richly dysfunctional town of Navolato, Sinaloa, however, and were killed, their burnt-out bodies found in their surf van.

End of story? Yeah, kinda is. The Men’s Journal, however, just dropped a long piece on the murders, documenting the doomed voyage from Washington in North America, through Baja, and onto mainland Mex.

Let’s study the piece.

In Baja the swell was epic. They ended up scoring nearly perfect surf. They camped on remote beaches, cooked meals on the sand, and woke at first light to paddle out. But after a week of waves, it was time to move on.

The plan was to take a ferry across the Gulf of California, the 140-mile-wide bay that separates the Baja California peninsula from the Mexican mainland, then drive south. It was 560 miles from the port of Topolobampo, Sinaloa, to Guadalajara. If they had any hope of making Coleman’s meeting at noon with Gómez, they’d have to drive through the night, taking turns at the wheel.

Then the ferry was delayed two hours. As they waited, Lucas sent a message to a friend in Edmonton, where he lived with Cox. “Can you do me a huge favor if you are seeing Josie?” he wrote. “We have our three-year anniversary tomorrow and wanted to get some things for her like flowers and red Lindt chocolate.”

When Lucas and Coleman finally arrived on the mainland, it was just before midnight. The two, together and on their own, had spent the last decade traveling the world racking up dozens of countries — South Africa, Sri Lanka, Iceland, India — as well as multiple surf odysseys to Mexico. They knew how to handle themselves in foreign lands, but it’s almost certain they didn’t know just how dangerous the stretch of road is that they were about to set off on. In the last two years, at least half a dozen travelers have been murdered on it, by bandits preying on motorists. On maps it’s marked as the Benito Juárez Toll Road. But locals have another name for it: the Highway of Death.

There is still a charcoal trace of burned earth off to the side of the tractor path where someone doused Adam Coleman’s van with gasoline and ignited it. When investigators picked through the debris, they found two gas grills, heat-swollen vegetable and soup cans, jars, dishes, and two sets of human remains. At first, police figured the victims for tiangueros, vendors who hawk their wares from street-market stalls in the city. In Mexico, 95 percent of murders go unsolved, so the crime was unlikely to warrant any special attention. It was largely a coincidence that led the police to look more closely.

During the long drive south, Lucas and Cox had been texting each other frequently. He’d tell her about the surf in Baja or include her in a discussion he and Coleman were having. So after receiving the flowers and chocolate, then not hearing from him for 24 hours, Cox had a feeling something had gone horribly wrong.

“I knew he was dead,” she says. “But the families were trying to keep positive.” Cox’s mother tried to assuage her fears, telling her that Lucas probably just got caught up surfing. Gómez was receiving the same sort of reassurances about Coleman. “I reached out to one of his friends and told him I was upset, and he tried to calm me down,” she says. “But more days went by, and we had to begin the search.”

Seven days after last hearing from Lucas, Cox posted an appeal on Facebook: “It breaks my heart to do this. . . . We are appealing for any information regarding Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman.” Gómez translated it into Spanish.

Pedro, the gas attendant who had given Lucas and Coleman directions, had seen images of the burned van displayed on the front page of a local paper. He recognized it immediately but had no idea who the two gringos were. Then he happened to see Gómez’s Facebook post, which had been shared widely.

“This is going to upset you,” he wrote to her shortly afterward. “Please stay calm and try not to panic. The van in this photo looks like your boyfriend’s.”

Suddenly the murders morphed from just another local tragedy into an international incident, with headlines around the globe. “Australian Surfers Missing in Notorious Sinaloa, Mexico,” ran a headline on an Aussie news site. “Australian Surfers Feared Murdered in Mexico During Quest for ‘Crazy Waves,’ ” ran another, in the U.K.’s Telegraph.

The Sinaloa attorney general took the rare step of holding press conferences to detail progress on the case. Within 48 hours of discovering that the van had been registered to Coleman, he’d announced, police had captured three suspects and had issued arrest warrants for two others. State marshals from an elite investigative unit had set a trap for the bandits, stopping them at 5 a.m. on a dirt road leading from a breach in the fence along the Benito Juárez. They recovered the getaway car, a Jeep Cherokee, and the murder weapon, a .357 Magnum revolver. They’d also extracted signed confessions from all three suspects in police custody.

At the wheel of the Cherokee was Julio César González Muñiz, a round-faced 27-year-old with a wispy mustache. The marshals, the arrest report notes, discovered the revolver in his waistband, and a ballistics test quickly matched the gun to a bullet removed from Coleman’s body. In the Cherokee’s passenger seat was the driver’s first cousin, Martín Rogelio Muñiz Ponce.

The details of what happened that night come solely from the confessions of the Muñiz cousins and Sergio Simón Benítez González, their supposed lookout. On November 21, shortly after González witnessed Lucas and Coleman passing through the toll booth, the Cherokee pulled out behind them and flashed police strobes on the dashboard. Lucas and Coleman continued to drive for another mile before pulling over. One of the trio’s alleged accomplices that night, José Luis Espinoza Bojórquez — who remains at large and has at least two other murder charges against him — stepped out of the Cherokee wearing the uniform of a highway patrol officer.

“They pulled two males out,” reads Julio César’s statement. “One of them was shirtless and wearing shorts and had long dreadlocks, the other was wearing dark pants and a black shirt.” Bojórquez forced “the long-haired one” into the backseat of the Cherokee and the other into the van and started driving to a nearby field, so they’d be out of sight. But as they exited the highway, Coleman tried to escape, forcing the Cherokee’s door open and jumping onto the dirt road.

A desperate fistfight erupted. “This guy was getting in some hard shots and beating the hell out of them,” the confession reads. Muñiz pulled out the .357 and “put a bullet in the gringo, getting him in the face.” Coleman was severely wounded, but not fatally.

At that point, Bojórquez, “furious from the ass-whipping he had gotten,” took charge. He jumped behind the wheel of the van while the others loaded the wounded Coleman and Lucas into the back. Soon they came to a stop at a tractor path dividing two cornfields. Bojórquez took the gun, then went to the hinged side doors of the van and fired four or five shots straight inside. The assailants doused the van in gasoline and Bojórquez threw a lit match inside.

There’s a twist to the story. Read it here.