Formerly, the king of Teahupoo, where this story takes place…

Paul Gauguin had it right. It’s the tropics, man. The palm tree, salmon sunset, rainbow tropics. The slow time, trade wind, warm coconut scent on a patch hot sand tropics.

And the best tropics? French colonial ones. Paul Gaugin had it oh so right.

But Raimana Van Bastolear has it righter. He is the eminence of Teahupo’o, arguably Tahiti’s most precious resource. Most surfers have consumed this mutant wave via magazine spreads and surf competition webcasts. There its craw gapes like a hungry troll. There it eats one surfer and sends another to barrel spit’d fame. It is adorned in Billabong, Red Bull, badly color blocked trucker hats. Its voice is a WSL commentator using adjectives poorly and metaphors hyperbolically.

In person, though, Teahupo’o is neither mutant nor surf garbed yokel. It is postcard with soaring green crags and lavender water. It is a pile of French rot at the end of a two-lane road and it is perfect.

Nothing, you see, rots better than French. It’s as if French colonizers, architects, chefs and priests in their wisdom, built a culture that looks and feels best coming undone. The Tahitians speak the language with a buttery patois drawl and it sounds more magnificent than it does on the Left Bank of Paris’s Siene. They worship God with many French misspellings in the prayer book and it becomes raucous southern gospel. They cook the food without actually cooking it, serving poisson cru bathed in coconut milk for every meal. They defy Western ambition by driving 40 km. Max. Which makes Western ambition seem a foolish pastime.

And I sit on a weathered deck hanging over perfectly temperate water and try to sit back even further. Like, the furthest back without actually laying down, soaking in the slow time and the French rot and not caring about anything at all. Especially not fast internet connections.

And even though slow time is one of the things that makes the tropics oh so right I see Raimana moving in front of my half-closed eyes, through the postcard, like a bolt. His cell phone buzzes. His jet ski whines. His many family members, friends, helpers, employees run this way and that, cooking, cleaning, sailing, loading, building. Being the eminence of any place is work but very much more apparent in the oh so right tropics.

To the uninitiated, the professional surf life is two very disparate things at once, free and structured. It is the vast oceanic playground sans the traditional “stick and ball” rules-based ethos. It is also a business where talents are groomed according to a specific, painstakingly followed, code.

This happens, of course, every winter on Oahu’s North Shore. Young charges are sent into homes owned and operated by the surf brands. There they learn where to paddle out, when to paddle out, what boardshorts to wear with what t-shirt, who to talk to and when, etc. Strict guidance is surfing’s manna.

The North Shore, however grand a social experiment as it is, is not the only school. Young charges get taught at contests, photoshoots, and when they travel to the middle of the South Pacific. It is, genuinely, a wonder that eighteen-year- old boys can even get to a place as remote as Teahupo’o to begin with. The nearest airport is an hour plus away, there are no hotels, real restaurants or infrastructure and the language, however buttery, can be a real barrier to entry.

Its remoteness necessitates a Raimana. He feeds, ferries and looks after the future of the sport. He also, quietly, provides the best education they will ever receive, as it relates to surfing one of the heaviest waves on the planet and living well. And this combination makes him invaluable.

I watch him while sipping on a lukewarm Hinano but watching Raimana’s spark I remember that without ambition there would be no refrigeration. Or colonization. And I hoist myself up to go speak with him, which is harder than it sounds. Raimana Van Bastolear is in demand. There is Quiksilver, and all the Quiksilver surfers, in one of his houses causing trouble and dreaming up schemes. There is a crew of seventy shooting a Visa commercial in one of his other houses. It stars Kolohe Andino, apparently, ordering pizza on a cellphone in a barrel. There is the Point Break production team, somewhere. There was Giselle Bundchen and a Chanel crew who just left. And there is the Billabong Pro coming in just five days and with it badly color blocked trucker hats and Red Bull.

Raimana runs it all and that is why this pile of French rot at the end of a two-lane road is called Raimana World. When I finally reach him (my legs feel like they are wading through sweet black molasses) I assume he is going to bark at me that he is busy (because he is) and send me back to my virtually laid-back position, warm beer in hand. I don’t necessarily rue this fate but he does not. He looks at me, eyes smiling, and tells me to meet him on the dock where we can sit with our feet dangling in the water because it is cooler then the deck.

Teahupo’o, the wave, can be heard thundering on the reef a kilometre out to sea and my very first question to him is how he first came to ride the wave. His face lights up. It is always light. It is warm like very few faces I have ever come across but it is both warm and wistful when speaking about that wave.

“Ahhhhhh I used to bodyboard out there in the middle 1990s. One day I was out there with my brother-in-law Kahea Hart…brother-in-law…that’s how you call your sister’s husband, yeah? Yeah. And anyhow he yell at me to go get him his board from the boat. So I paddle to the boat and get his board and start paddling it back out to him. He used to ride for MCD. Remember MCD? Used to be owned by the same guy who had Gotcha? Ha! That guy liked to party. And I was paddling back out when a huge set came through. I was in position because it swung wide and the boys were shouting, ‘Go Raimana! Go!” So I went. I paddled into one and got barreled. That was my first wave surfing out there. It was a two-page spread in Surfing magazine.”

Every part of this first story is perfect. A young man lost in bodyboarding’s false glory is perfect. A call to surfing arms is perfect. More Core Division and its place in fashion’s lore is perfect. Micheal Tomson is always perfect (he really does like to party). And getting a two-page spread in a surf magazine on the first wave ever ridden while standing up is perfect. It is so perfect that it sounds apocryphal which, in turn, makes it so very French, Joan du Arc-style French, and it feels just like it should.

Raimana’s expression does not change during its telling. He is neither reveling in his own legend nor disappearing behind a cloud of false modesty. It is as light as Scandinavian summer and as easy as Sunday morning. I hear a bustling off to my right. Raimana’s people are loading a boat with either Point Break people or Visa people. His cell phone buzzes but he ignores it like he ignores them and keeps his focus straight ahead.

I gesture while asking, “How did you go from a bodyboarder cum surfer du jour to the man in charge?” and he stays the same amount wistful.

“Soooooo it was back in the day and I was cruising in town and I saw Pancho Sullivan and Noah Johnston sleeping in their car on the beach. I went up to them and said, ‘Where are you guys staying?’ and they said, ‘Here in our car.’ and I said, ‘No way. You come and stay with me in my house.’ They came with me and then went back to Hawaii and told all of their friends, ‘Hey there is this guy Raimana and you have to stay with him when you go out and surf Teahupo’o so then all the boys started staying with me…”

A boat speeds near, cutting the engine right in front of Raimana. Its driver shouts something in sexy, decrepit French. Raimana answers in the same patois. The boat driver nods, sparks the engine and speeds toward a sun sliding lower down the sky. Watching the boats, here, it is amazing that more of them don’t end up on the reef. They fly so fast, skirting deadly shelves with studied abandon. I would, for sure, put all of the boats on the island on coral outcroppings, if I was left in charge, and it would be a monument to myself and oceanic incompetence but also a roaring good time.

Raimana watches him go and then turns to me again, having lost his train of thought.

“…what was I saying again?”

I tell him, “About Hawaiian surfers who flocked to your home but that part I get. Surfers are always looking for maximum ease and your home on the beach, as close to the wave as possible, provides maximum ease. You could have fed them Spam and had them sleep in hammocks and they would have kept coming. But Visa and Point Break are two different things, altogether. Those sorts of bastards are demanding…to mention nothing of Giselle.”

Raimana does not struggle to come to terms with the difference between feral Hawaiian surfers and international supermodels. He answers both quickly and at once, “I love to show the world what we Tahitians have. We have so much to give. There are no paparazzi here. The people respect each other, pretty much, and respect the stars. No one approaches a famous person and says, ‘Whoa! Give me blah blah blah.’ They either ask first or just let people be.”

It could sound like a cliché except it is not.

Corporate interests, which grow in both size and scope, and celebrity guests, which flock more and Johnny Depp-er are testament to the special little world Raimana has built on the back of a decayed colonial system. French hospitality has never been a “thing.” Gauls are known for superiority complexes, snootiness and a general dismissiveness of all things non-French. But “French hospitality,” coming undone in tropical Tahiti, is, again, the dream at its zenith. It is not that Raimana is overly attentive to the needs and whims of monied Western interests. It’s, maybe, that he provides them enough to be happy, in the simplis and no more.

Roofs, if they need. Boats, if they need. Food cooked simply by his family, if they need. Otherwise people are left alone in a tropical milieu that will drive the most heartless toward luminescent adjectives.

Another boat speeds toward Raimana. This time its driver doesn’t bother speaking. He just contorts his face in a way readily understandable then speeds off. So French! I ask Raimana if all of these boats are his and he laughs. “No. I owned a boat for a little while but then sold it and now I just rent them from the guys.” So smart! It is a known fact from Papeete to Pittsburgh that boat ownership is a losing proposition. It is pure ego and Raimana does not want or need the extra headache. He is smart enough to know where living well runs over pride and consumption.

I ask him what his big dream is. Does he, for example, want to build a hotel on this magnificent land and get rich and host Vanity Fair parties? He laughs again, “No no no. What I would love to do is buy a big piece of land and build one house, like the Volcom House on the North Shore, where all the surfers can live together like a family…”

The houses he has now are not quite big enough to host everyone all at once. Team managers, photographers, surfers and various hoi polloi scatter between a few houses that are all beautiful and simple but still scattered. “…and then I’d build one house for corporations or people who want to come over here and do stuff but that’s all. I wouldn’t do anything bigger because then you can’t give the people quality. That’s why people come here. They spend all that money on plane tickets and rental cars and they come here and just want to be taken care of. It’s the one time in their lives that they can get that and that’s what I want to do.”

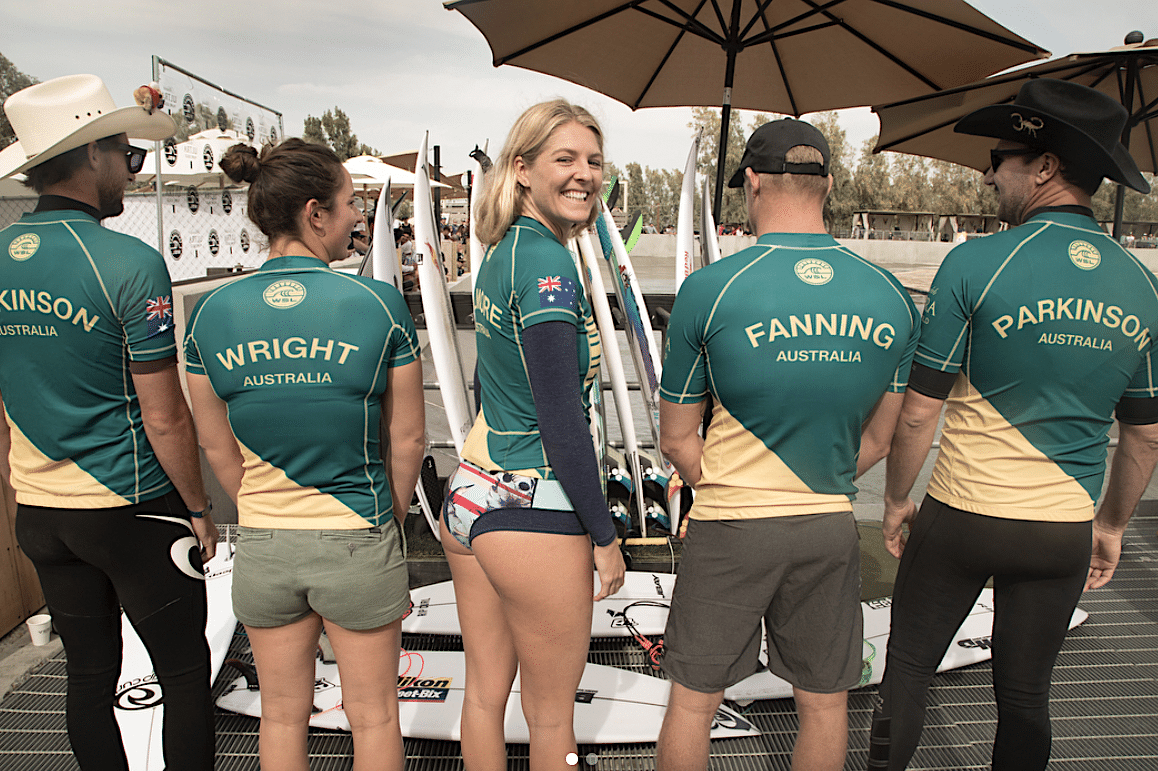

Again, it sounds cliché but speaking to the Quiksilver team, currently occupying one of the houses, their experiences at Teahupo’o are exceptional. They feel safe on an extremely unsafe wave. They feel cared for even though their own families are thousands of miles away.

Raimana wipes a bead of sweat from his brow and I ask, “To what end? It is very great to provide such a wonderful time to foreigners, and also to help prop up the local economy, but what is in it for you?”

And there is that smile again, that magical tropical smile. “I still want to surf those big waves at Teahupo’o. I want to do what Laird does. He is 50 and still playing in the ocean. I want to play in the ocean.”

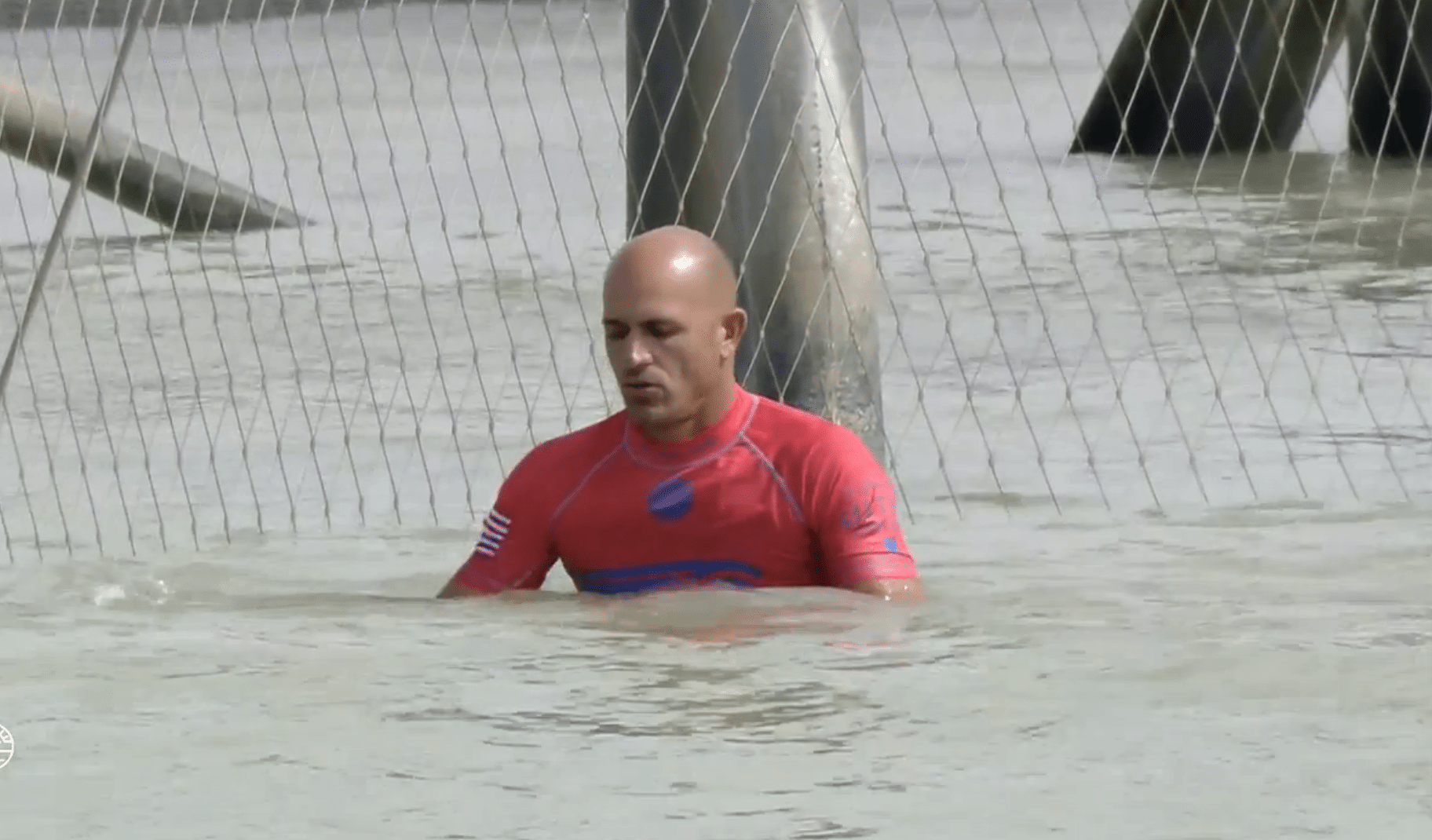

And with that a third boat driver whips in. There is some minor emergency somewhere and Raimana is needed. He bows out, politely and apologetically, and I hop on a vessel heading out toward the wave. The sun is low now and everything looks ridiculously beautiful as we skim over turquoise, blue, green velvety water. Then I see the iconic judges stand bolted to the reef. Then I see the wave itself, which is jaw-dropping to even the most jaded of surf journalists. It is not giant Teahupo’o but it is big, solid and spitting. Koa Rothman and Mikey Wright hoot while hopping out and joining the rest in a lineup getting ready for the contest. I ask the photographers and Quiksilver’s legendary Nicholas Dazet, who remain on the boat, if they have ever surfed it. “

Are you kidding me?” is the consensus. “Anything that is safer when it is bigger is not to be touched.”

I happily sit and drink it all in as the sun goes very low. It is the tropics, man. The perfect Tahitian coconut scented tropics.

And when the sun is all the way gone and the stars twinkle overhead the boat heads back to one of Raimana’s houses. A feast has already been laid out and cast and crew launch in with reckless abandon.

I sit at a quiet corner table with Raimana and his mom. He seems exhausted, eating his French bread and poisson cru slightly hunched over, but he also seems satisfied. The young charges are safe. The Visa crew, in another house, got the clips for which they came. It has been a successful day. We make small talk, surf gossip, laugh and then he excuses himself to go sort another minor emergency.

Soon the Teahupo’o season will come to a close and Raimana will have a moment’s peace. He can let the slow time wash over him. He can dangle his feet in the water and drink lukewarm Hinano and just be.

We are passing through, but at the end of the day, it is Raimana World. Or as Jay-Z says, “I’m not a businessman. I’m a business, man.”

(The Surfer’s Journal, as discussed on this very website, is a thing of art and I am lucky enough to, at times, contribute. Some time ago, I wrote a story on Raimana Van Bastolear, the mayor of Teahupo’o.)