Final day reflections on surfing's Brave New World…

I’m standing in front of the stage, waiting for the awards ceremony. A perky song plays over the loudspeakers. Steph Gilmore dances in place with a million-watt smile. Though some people have left for the day, there’s a solid crowd gathered. Hay bales covered with beach blankets serve as seating. I’m waiting for Kelly. So was everyone else.

Free of my cameras’ weight, and the need set up specific positions, I’d wandered more widely today. It was hotter than Saturday, even with the breeze. The left had an onshore. I’m not even sure if that’s how we’re supposed to describe it now. But it was onshore. The wind gave the right a slight texture that wasn’t quite a true offshore.

When construction started on the Surf Ranch, he’d thought they were building a wave to boogie board. Maybe $10 for the day. The reality was a long way from what he’d imagined and he was having fun.

We don’t have a language for all of this just yet.

I talked to Jonathan, a mechanic from the local navy base. He works on the F-18’s that occasionally overflew the lineup. A friend lived a mile or so away from the Surf Ranch in Lemoore and they’d wondered what was behind the fence. By the time he bought his ticket, only Sunday was available. When construction started on the Surf Ranch, he’d thought they were building a wave to boogie board. Maybe $10 for the day. The reality was a long way from what he’d imagined and he was having fun.

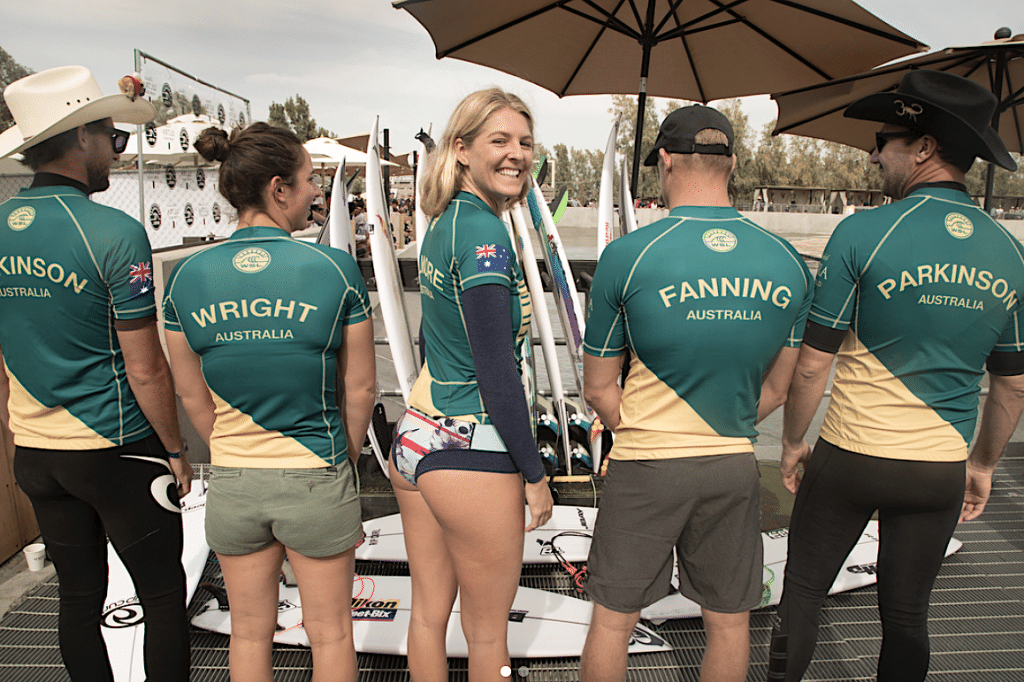

After the morning round, I lost the plot and had to reread the format. I confess, I had a hard time keeping it in my head. During Brazil’s final round, I stood near the team area, designated for athletes and staff to watch the event. They were pure joy. They sang and clapped. Then they sang some more. I decided that I wanted to be Brazilian when I grow up. They made me care desperately about the outcome. I enjoyed the feeling.

The most popular viewing spot by far was the middle of the pool, where you could see turns on both the left and the right. The low-growing trees that run at intervals along the pool’s edge were also almost certainly a draw. Lots of people brought beach chairs and lounged comfortably. They had the right idea.

I ran into one of my neighbors from Santa Barbara. He’s Australian and was there with a crew. He likes parties and surfing, and figured why not come out for a chance to combine the two. I ran into them in the VIP zone, but they said they’d walked, like, six miles on Saturday to see every angle. You and me both.

O’Neill. A surf shop. Another surf shop. Hurley. I read the t-shirts as I walk down the line. Most of the men are in boardshorts. The women are in cute dresses or cut-off shorts. The crowd who buys tickets to surf contests plainly also buys surf t-shirts and boardshorts. There, I did your market research for you.

I stand in a knot of fans under the trees. Someone surfs by on the right and enters the barrel. A grom watches avidly. “That’s the only part of it I care about,” he tells his friends. He’s already well-traveled. He’s wearing a shirt from a surf shop in Panama.

I watched Toledo’s last two waves near a group of Brazilian fans. They chanted his name rhythmically. When he fell, they were devastated.

By Sunday afternoon, sunburn had reached epidemic levels. In the VIP area, there were Sun Bum bottles on the tables. This is the kind of brand giveaway I especially appreciate. Useful, relevant, well-played Sun Bum, well-played.

A thoroughly sunned-out crew from Santa Cruz held down a space near the start of the right. They wore boardshorts from assorted brands, extensive tattoos, and not much else. One wore a Trump hat, another wore two pairs of sunglasses. They waved an American flag with vigor and animation. When the time came for Kelly’s final waves, they heckled good-naturedly, entirely without malice.

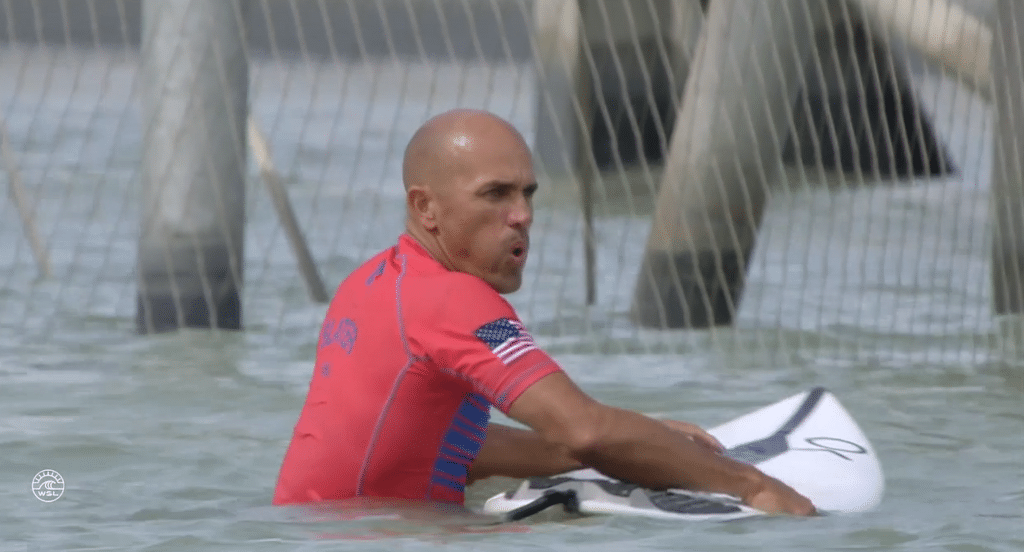

As Kelly surfed his final wave, I sat in the crowd, who reacted to each and every turn. At the end of the right, he went up for a final air. The crowd went with him. They wanted him to win so badly. When he fell, there was a collective groan. No. He couldn’t possibly have missed it. He’s Slater. He always wins. Not always, not this time.

I watch the awards ceremony. I check my voice recorder. I read my notes one more time. I’m brought past security and through the fencing behind the stage. I wait where they tell me to wait. The waiting is sometimes the hardest part of this job. You have to stay there. You can’t lose sight of your mark. So you wait. I’ve learned eventually the art of patience and the ability to stand in exactly the same place for as long as it takes.

Slater’s mom is behind the stage wearing an orange shirt with matching lipstick. She chats cheerfully with his publicist. She’s wearing a necklace with a VW bus charm that’s painted with bright-colored flowers. Slater comes over after the awards are complete and the warmth of their relationship glows amidst the chainlink fencing, the dust, and the security guards.

Slater is pulled away for a quick interview. And then for a photo. Then he disappears into a tent. Still, I wait in the same spot, my feet barely budging at all.

And then he’s done. It’s time to move. I’m to follow him as we walk from the secure area behind the stage to the Outerknown booth where he’s due to do a signing. It’s not much more than 20 feet, maybe less. The security guard shifts position. We walk into bedlam.

When Lance Armstrong used to pass through crowds, he’d walk fast, head down, without making eye contact. He was like a ghost, passing through the world as though nothing existed around him. I’d guess the crowds registered with him, but he’d keep walking.

Slater seems to know he should do it that way, but it also seems as though it’s hard for him to say no. I’m on his outside and I turn to look toward the crowd, to see it as he does. A wall of phones. Outstretched hands. Kelly, can you —

I move ahead. I reach the booth just ahead of him and the crowd slams in. We’re in a fish bowl. They watch avidly as I ask my questions. Slater loves talking about surfing, but our time is limited. I ignore our surroundings. A videographer moves in close. I hope my my face is clean.

I tell him about the grom, the one who was so stoked on the barrels. Kelly’s whole face lights up. It’s like I’ve brought him a gift. It matters to him that people like him, I think. I feel like it’s the least I can do. After all, I’m just one more person asking for a piece of him.

We finish talking and I stand for a moment just off his right shoulder. The crowd pushes closer. Phones up. Hands reaching.

I walk out of the light, grateful to escape.