"I hope he is lauded for the way he left surfing — for Paris, Tokyo, New York; for ateliers, design studios, clubs, foreign-language magazine racks — then just as eagerly returned to cross-pollinate our beautiful but woefully inbred sport."

I have no doctor’s note to prove it, but at the south end of my duodenal bulb, hard against the superior flexure, is a nubbin of scar tissue marking the place where an ulcer sprouted and flourished over a six-month period in 1986 when I dated Michael Tomson’s not-quite-ex-girlfriend.

Just an extended summer romance. Nothing at the outset, flirty and harmless, haha, nobody even knew!

Then a friend of mine who was also a friend Michael’s pulled me aside and matter-of-factly reported that Michael found out and was going to “serve my head on a platter,” and I didn’t get a restful night’s sleep until late 1987.

Michael Tomson was overwhelming.

In all things, for better and worse. I use the past tense, which is not technically right, although week before last I got a message that he had advanced throat cancer, followed by a second message that he had died, then a third and final message that he was alive but in bad shape and not expected to recover.

Write about him now, while he still might read it, I was urged. Do not hold back, jump all the way in, that’s what he’ll want.

Michael’s legacy is and will always be divided into three parts. The easy, uncomplicated, foundational part was built wave-by-grinding-wave at Pipeline in the winter of ’75-’76.

At that epochal Free Riding moment in time, Michael was, let’s say, 60% the surfer his cousin Shaun was in terms of raw talent.

Was that hard to live with?

Probably.

But my guess is that playing second banana throughout his formative years to a younger and slightly better-looking relative had much to do with what Michael achieved in his career, beginning at Pipeline, where he never out-surfed Shaun but often out-gritted him.

Shaun was a surgeon on those big hollow walls. Michael was a bull at full charge with six banderillas stuck in his back.

You couldn’t take your eyes off either of them. (How did Michael get ready for Pipe? Easy, surf Waimea. “After Waimea, it makes going back to Pipeline much easier. And Sunset’s a joke after Pipeline.” Read the full interview here.)

The second part of Michael’s legacy is Gotcha, the wildly innovative and successful company that he co-founded in 1978 and into which he poured all of his fissioning talent, taste, ambition, and vanity.

Gotcha was, above all things, a big blaring Moulin Rouge-level spectacle.

Throughout the 1980s, you never knew what the company would do next, except that, like Michael himself, it would be outsized and extreme. For me, the Gotcha project was always hit or miss. The Gotcha Pro, spawn of Mardi Gras and the Op Pro, was a gaudy, bloated world tour setback.

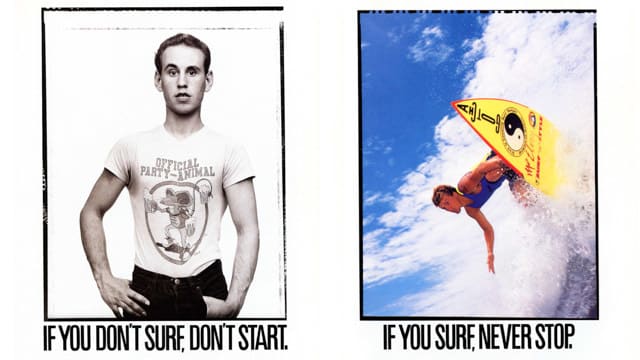

Gotcha’s infamous “If You Don’t Surf, Don’t Start” ad campaign, with its gallery of American non-surfing and therefore unworthy archetypes (fat kid, old person, street-tough) juxtaposed against color action shots of Gotcha team riders — the cool kids — was mean, petty, awful.

But the energy pouring forth from Gotcha’s Costa Mesa HQ, month after month — the sheer creative horsepower, the audacity — was miles ahead of any surf commerce entity, and I don’t just mean Quiksilver and Billabong, but all of it, the mags, the boardmakers, filmmakers, everything.

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say the whole sport was slipstreaming behind Michael and Gotcha. Nobody else could have made Surfers: the Movie, for example, which I’m glad to see is now in the Best Surf Film Ever conversation.

The third and final part of Michael’s legacy will be his enduring and literally all-consuming cocaine addiction, which Chas Smith calls “Shakespearean . . . a forty-year dance.”

Tomson’s longtime friend Phil Jarratt wrote about it in 2015. Tomson himself unapologetically spoke of his drug use, and much more, during a conversation with Smith less than three years ago (read here), in which he throws his head like a bull and is thus recognizable as the surfer he was in 1975, but is now swaying and about to buckle at the knees.

Both pieces are difficult to read.

I hope that Michael Tomson is further remembered and lauded for the way he happily, eagerly, relentlessly left surfing — for Paris, Tokyo, New York; for ateliers, design studios, clubs, foreign-language magazine racks — then just as eagerly returned to cross-pollinate our beautiful but woefully inbred sport.

That was the plan (read here) from the very beginning.

If you have a Gotcha-era surf mag handy, open it up and look how flat every non-Gotcha page looks by comparison. When you watch Surfers, remember that Michael was stealing, to our great benefit, from Rolling Stone, not Bruce Brown.

Hell, at one point this crazy bastard had us all wearing elastic-band madras-plaid Bermuda shorts!

For 35 years I have been both awestruck and ambivalent about Michael Tomson. He is tragic and fantastical, but familiar.

His love of surfing is mine.

His nihilism is a distant cousin to my mostly outgrown but still vibrantly recalled selfishness.

Maybe some of you feel the same way.

“I’m not bold enough to be Michael Tomson,” Chas Smith writes, “so I need him to be Michael Tomson for me and to hell with the price — physical, financial, emotional, mental — that he has to pay.”

(Editor’s note: Every Sunday, Matt Warshaw, keeper of the Encylopedia of Surfing, sends subscribers a longish form email describing his historical adventures of the week, with nods to contemporary events. It’s a fine thing to receive amid the tidal wash of emails offering clothing sales and discounted trinkets and, if you surf, it’s as essential as wax and, for three bucks or whatever it is a month, cheaper.)