"A place where the monkey will live a life that other monkeys only dream."

Reports from Hell will officially loose onto the public this Tuesday, Aug. 11 Here is an excerpt. Buy here, here, here or here if you’d like to partake in a wonderful live reading on Wednesday, Aug. 12

Djibouti, Today.

“Wait. I really don’t understand. Why were you kidnapping a monkey again?” Nate twists around on his baking hot wooden bar stool underneath a thatched roof covering the outdoor bar of Kempinksi’s Djibouti Palace. The bartender, a kind-faced Djiboutian woman with a loose scarf covering her head, is listening, waiting until I finish whatever it is I’m going to say before kicking the blender to life again.

Nate is looking at me and the back of his white button-up is drenched in sweat, though the front looks remarkably dry. The half- Windsor knot of his pencil black tie is slightly loosened as a subtle nod toward the extreme temperature, but that’s all. His two-year run in Baghdad as a liaison between the United States of America Army and the international press had served him well.

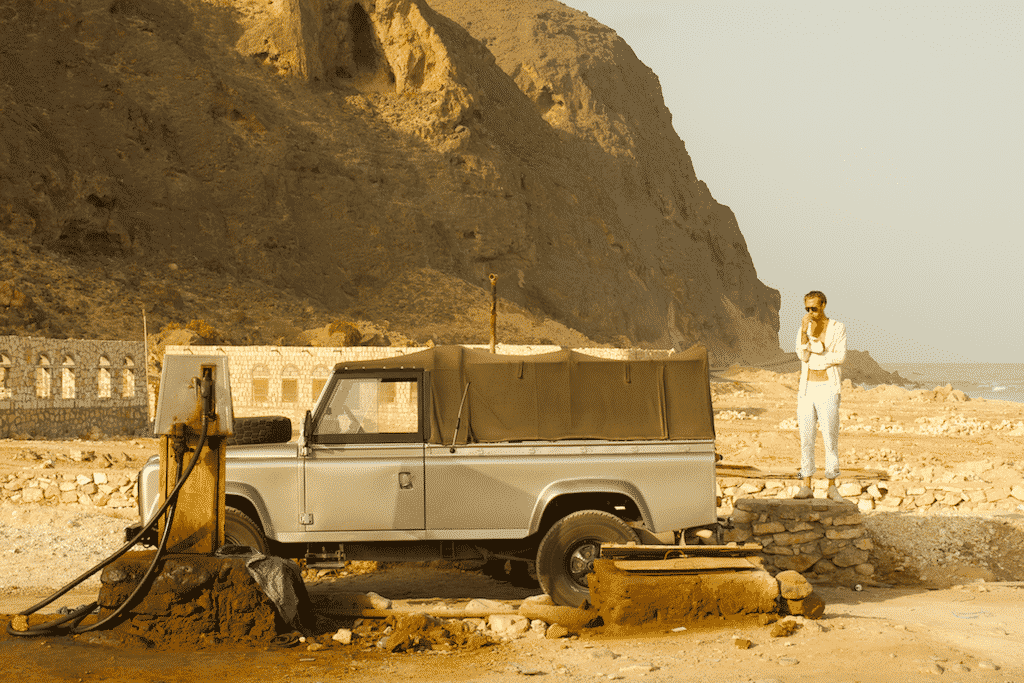

He chased that gig by cofounding a high-end design-build firm that operated out of Kabul and Sana’a with Josh, who gave up on being Islamic Studies’ enfant terrible and decided that what Kabul and Sana’a needed was a high-end design-build firm.

He and Nate spent years on daily flights, shuffling back and forth between Kabul and Sana’a before the whole region blew up in a new fiery ball. Nate mostly keeps his work secret now and refuses to respond to direct questions, so it’s mostly impossible to know what he does with his days. The only thing I know, for a fact, is that he attends Elton John’s annual Oscar party each and every year. Josh is back in Los Angeles, collaborating with Jay-Z and Beyoncé on something I’m equally confused about.

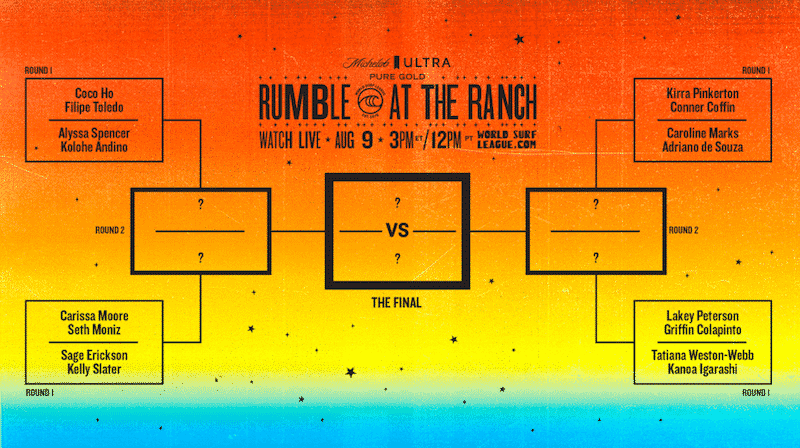

And I quit my job at Los Angeles City College to become a fulltime surf journalist. A literal and honest surf journalist. The fact that such a thing exists is absurd enough. The fact that I do it pushes it right overboard.

“Because, bro,” I say between sips of still cold piña colada that I insisted we all order since the outdoor bar has a thatched roof. “Josh was right and you were right. Being on camera is true hell and we were never meant to be famous in any sort of actor-y way. Our trajectory was never supposed to be tied to being famous.

That’s the simple truth, and I understand it now. Sorry for making us pursue cellulite stardom all these years. It wasn’t a well-thought- out plan.”

Josh snorts from his bar stool.

Nate says, “Celluloid.”

We had flown to Bombay just a few short months after returning from Yemen triumphant, though completely exhausted and filthy. Mimi had watched the footage and was excited to keep pressing.

“You’ve discovered something so fabulous, darlings…” she breathed heavily the day we arrived home, exhausted and dirty. “We’re leaving as soon as I get the rest of our budget to…where? Where is that fabulous school where they teach the radical Islamic terrorism?”

“Deoband, India,” Josh replied.

“Absolutely gorgeous, and I’ll come too. India is marvelous, and this Deoband sounds very chic.”

We were too tired to argue.

So there we all were, night one, in the bar, a monsoon rain pouring outside with our Punjabi bartender towering above us when Mimi told Tony to pull his camera out and get some real descriptive interview. The bartender was in a Sikh motorbike gang, very tall and handsome, and looked on, interest piqued.

Josh nominated me to start and Tony swished his brown corduroy pants over to his camera bag, set it up, and turned it on me and said “speeding” while clapping his hands in front of the lens.

Something happened in my heart when I saw that little red light come on. Something deep and profound that I can’t quite explain. I just knew, in that moment, that I hated being on camera. I hated it in Lebanon, I hated it in Yemen, I hated it in Bombay. Hated everything about it. Hated the way it made me feel, hated the way I looked afterward, hated the way my voice sounded. And for the first time in my life, I thought, “Those cultures that believe the camera steals your soul are right.”

I looked at Josh for help. Tony swung the camera his direction and I was momentarily off the hook. Josh fiddled with his rings for a minute, explaining some deep cut seventeenth-century Islamic nugget before excusing himself for a cigarette.

Tony pointed the camera toward an ornate picture frame, and I wasn’t at all upset with him. It was very beautiful.

That night, after Josh and I got back to our room, I sank,

emotionally, and moaned, “This fucking sucks.”

Josh laughed. “After just one take? Come on. We went all the way

through Lebanon, twice, with cameras, and now Yemen without you

pitching a fit. You’ll smash it tomorrow. It’s what you want to

do.”

It wasn’t anymore, that dream evaporating in a millisecond and leaving nothing behind, but how could I tell Josh that? I had wrangled us into ugly relationships with Vice, Fremantle, Al Gore, and now Mimi, all in the hopes of a cinematic capturing of the lives we led instead of just enjoying them ourselves like he had wanted all along.

I headed over to the TV and magically found a Lebanese music video station. “But I won’t,” I told him, dejectedly. “I know this time for a fact, I won’t. I have a horrible sinking feeling in my gut that I won’t be able to ever look good on camera. Not tonight. Not tomorrow. Not ever.”

Josh laughed again. “On the plus side, it looks like we’ll be paying out of pocket for Mimi and Tony the whole time. That’s fun.”

Mimi had “accidentally” forgotten her credit card back home but was “getting it FedExed straight away.” Tony wore brown corduroy pants. And the “film’s budget” seemed like it might have been spent on drapes for a Beverly Hills apartment.

“This is a disaster,” I moaned again, falling onto the bed. The first actual disaster of our run together, which up to that point had featured a weeklong hospital stay replete with IV bag after IV bag into my veins, which were shutting at an alarming rate; our theoretical lives being threatened by a sword-wielding Somali; hookers that we didn’t pay for or want secretly destroying our personal property; getting told we were awful at skateboarding by a Hezbollah officer so unversed in skateboarding that his honest assessment would ping until this very moment; and almost dying astride spray-painted Chinese motorcycle toys.

“Is this how all those damned Disneyland employees who call themselves actors feel?” I asked the ceiling. “A delusion of possibility that, carried by its own momentum, propels a man or woman to the ripe old age of forty still believing he or she can be someone who matters?”

Leih Beydary has given way to some older, seemingly wealthy woman crooning passionately alongside a tuxedoed orchestra in front of some dramatically lit ruins.

“This is shit,” I continued to mutter. “Absolute shit.”

Josh smirked at the TV then looked at me. “Wait, are you saying this trip is shit? Seriously, help me understand. Why are you so bent out of shape here? I’m sure if it’s what you want you can totally figure out how to be good on camera. Look at…Ben Affleck.”

“Yeah, look at him,” I said. “He basically carried Good Will Hunting, but I don’t want to be an actor anyhow. I just knew in my heart of hearts that this thing, what we do, whatever you want to call it, would get carried along via visual representation. But when Tony’s camera turned on today, it was like peering into a succubus. Or…what is the girl demon that sucks your soul?”

“A succubus,” Josh said. “The man demon is an incubus—just like that super sick band.”

“Maybe I’ve got Incubus sucking my soul, but I don’t know if I can come back from the way that felt. I hate to keep coming back around to damned feelings here but—son of a bitch—I’ve spent our entire run, through Yemen, Lebanon, Syria, Somalia, Yemen, India, building for this way to represent what we do in a way that actually looks how it feels. But today, something snapped.”

“Yeah,” Josh laughed. “But I think you so quickly forgot the amazing company we have along for the ride. That makes it worthwhile.”

I grunted and laid my head down on a starchy pillow. It was too early in the evening for sleep, considering the thick jet-lag on the horizon, and I knew I was just giving in to the sirens calling me toward rocky shores but it was better than thinking about Incubus anymore. Josh was right. He had been right all along. I closed my eyes and drifted into the blackness. Maybe sleep would change the predicament. Maybe sleep would give me some new insight into how to carry this thing. Maybe sleep would…

I woke up exactly at 2:15 in the morning, the red digital numbers of the bedside hotel clock shining like a beacon beaming the address of hell. The dread had not only not abated, it was strangling me. It had its hands around my throat choking my will. I stared at the ceiling, the dark cracks that ran away from the overhead light, a spider in the corner catching malaria for snack. What were we going to do? What on Earth could we possibly do?

“We’re going to steal a monkey.”

Josh’s voice cut into my despair so clearly that I thought I was only imagining it.

“What?”

“We’re going to steal a monkey, or get a monkey, and take it to an epic monkey temple up past Deoband that I heard of last time I was here. A place where the monkey will live a life that other monkeys only dream. That’s what we’re going to do.”