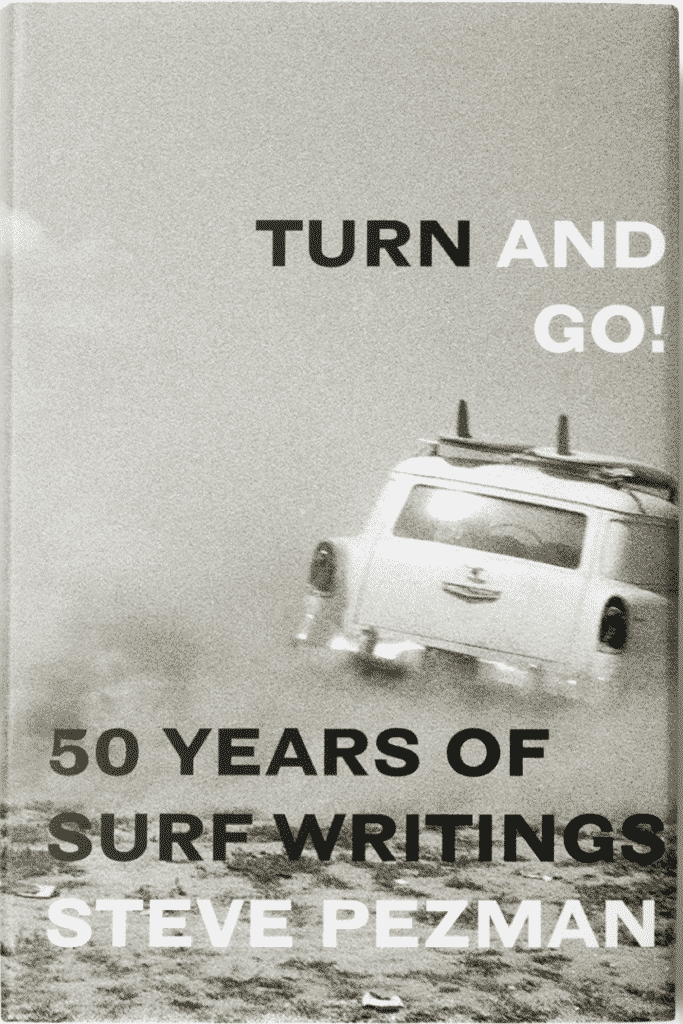

Read the stunning foreword to the hottest new book in surf!

My fondest memories as an editor lay in the years 2000 to 2013. The pleasures of the internet were extant, but not yet all-consuming.

Social media was largely the province of teenagers. Physical surf checks led to shit-talking, issue brainstorming, and talking story. The time passed quickly at TSJ, and we greeted each workday with the anticipation of Christmas morning.

What new submissions might arrive?

What fresh stack of transparencies from some far-flung locale or undiscovered archive might be unearthed?

Which page from the bedside notebook would take flight, hammered into shape as a feature by the print-world alchemy of writer and shooter and designer?

The rush of seeing the work in print, the preferred form for surfers everywhere. The joy of pacing out a year with the assumption that the issues would be cataloged on private surf shelves and tables for years, perhaps decades.

It wasn’t high art or Austrian economics. But it was, and remains, fun stuff.

There was a fetching magnetism at play, and visiting surfers, writers, and photographers couldn’t help but feel it. We jokingly called it the ivory tower effect. The Journal was taken seriously out in the world, but to us—the makers— we never wore like that.

The high-end feel of the physical product allowed us the chance to stay loose and broad-minded, thereby reflecting the topic. We were free to pursue the things that drew us in in the first place.

Adventure, both attainable and more aspirational. The vibrant, balls-out history of the pioneering players. Travel. Waterman lore. Individual expression. Commercially unfettered, we simply steered away from the parts of surfing we didn’t care about (scant little, to be fair) — mostly organized-surfing stuff like pro contests and pop-idol BS.

Turns out that it struck a chord.

We clocked 110 percent growth during those years — unheard of for a “mid-career” title at millennium’s dawn — moving from quarterly to “five-erly” to bimonthly.

That angle served us well. We’re here. Everyone else is gone.

It started from the top. Management-wise, one of Steve Pezman’s koan-like mantras was typical of his laissez-faire personal belief system: “It’s not a problem until it’s a problem.”

And when you had Pezman’s dead-to-rights eye for talent who might go the distance — ten or 15 or 20 years — it was hard to argue. We’d commit seppuku before letting our life’s work go tango uniform.

Potentially losing the readers ran a razor-thin second. Our sponsoring advertisers? They appeared to trust us explicitly, with nary a veiled checkbook threat.

There was an easy jocularity at the dojo, with a light crew floating ideas in a free-minded spirit. Like today, the players were there for exactly the right reasons.

And a couple of times a week, we’d come together at a local hike-in surf spot. It was a study in easy efficiency: a ten-minute drive, an hour surf, and 30 minutes for lunch. If I roll my eyes back and summon the days, I can remember each one:

It’s 2 p.m. on a Wednesday, 2013. That calm, sun- stroked, after-surf feeling prevails on the back patio of La Tiendita Market in San Clemente. Nothing fancy-boy. No nouveau, middlebrow affectation. A taco joint. Utterly surf.

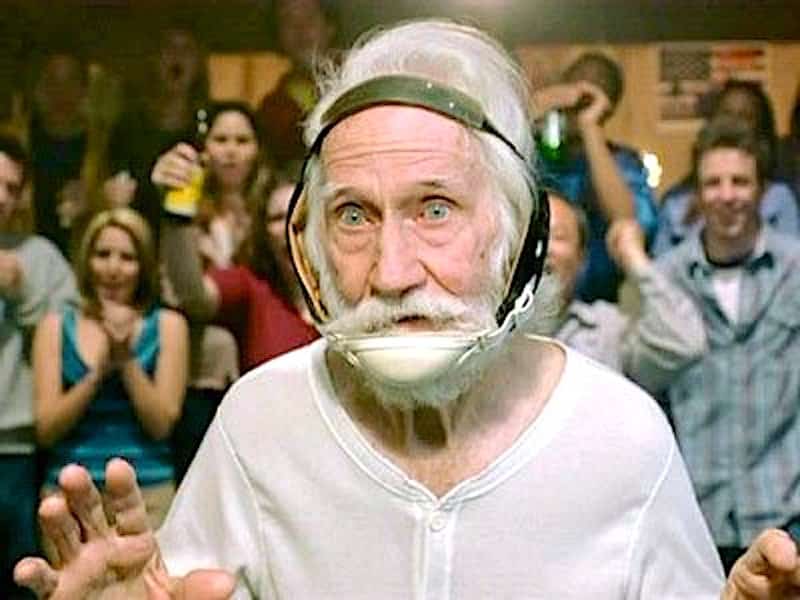

Chomping on a shard of adobada tostada, Pezman mentally lines up his shot. Errant bits of iceberg lettuce festoon his Metzger Plumbing T-shirt. Everything on his plate has been mixed together and doused from a palette of sauces.

Now he pours from a ramekin of chile de modesto he had asked the taqueria to produce. (Note: Pezman makes ad hoc collages from any offering: an onion-pancake platter from the Chinese-Muslim joint; the preciously plated assemblages of St. Helena; a backyard Fourth of July picnic. No LA Times– approved chef of the season is beyond such wood-chipper treatment. Pezman unashamedly identifies as a “foodie,” that normally cringeworthy semi-portmanteau of “gourmand” and “yuppie.” It’s a misnomer. He’s a surf trencherman through and through. Banquet bosses fear his advent, perhaps knowing of the record 17 ice cream sundaes he once slayed at Haleiwa’s Jerry’s Sweet Shop.)

The next bite of adobada can wait.

“I think I learned how some writers fluff a novel up to 400 pages,” he says.

He references a Harry Hole crime book. He’s a sucker for the genre and always knows the loftier offerings.

“Turns out you can coax a thousand words out of a simple description. An overripe tomato, a handbag. Anything, really.”

This revelation will be shop-tested later the same afternoon as he’s writing the intro to an interview. Indeed, he’s as excited to get back to the office as he was to surf.

We all are. Round pegs in round holes.

Pezman is always curious about craft, and he takes the hows and whys of magazine-making seriously. But then he’s always had a keen and youthful enthusiasm for his many pursuits: surfing, painting, tennis, dining, reading.

When it comes down to practice, like all masters, he makes it look easy.

No time for pinched-up angst.

“We surf-mag makers happily toil in the toy department of world affairs,” he says.

Magaziners are born into the game, not by birth, but by lifetime of habit.

In this game, it comes down to story.

And it’s a rare editor/writer/publisher who is not a ravenous reader of fiction, a student of fine art, of street and portrait photography, of golden-era-to-now book design.

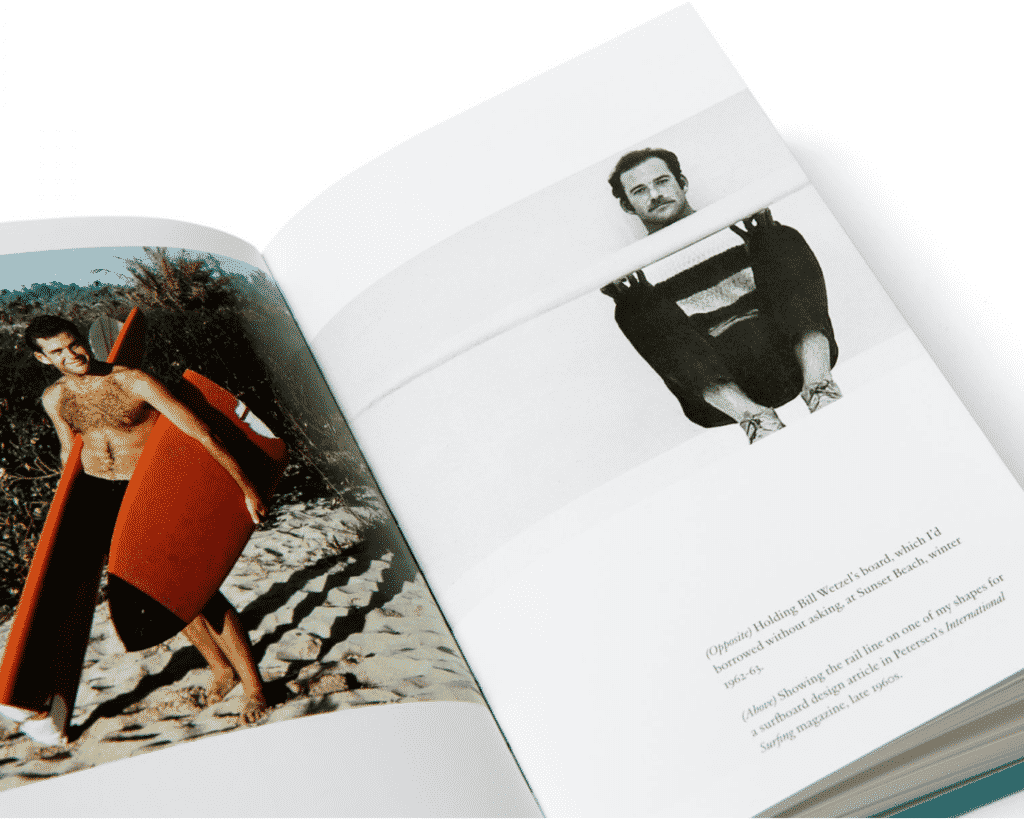

And Steve Pezman — as the son of a playwright who lost his job after the Hollywood Ten blacklist fallout — is no exception. He reads greedily and was something of an art phenom as a boy.

During his days at Surfer magazine, his battlefield promotion from editor to publisher happened fast, forcing him to exploit his innate —and, as it turned out, estimable — business sense.

This implies a pivot from art to commerce, but Pezman, having come from the edit side, maintained Surfer’s focus on sharp writing for his 20 years there. Though marked by a facility with numbers, it was the story, in words and with pictures, that thrilled him.

During the heyday of print, all of the surf monthlies had fine photography. The separation points were often the word furnishings: concepts, titles, captions, and, of course, the written pieces themselves. Pezman immediately surrounded himself with complementary lifelong lovers of magazines.

For better or worse, surf mags – as minted by patriarchal surf figure John Severson — rarely embraced straight, source-based journalism.

Like his contemporary Drew Kampion, Pezman captured the times as he saw them. Voice, afición, nuance…

The American surf magazine (and thereby every one of the international versions that drafted behind the originators) never trusted journalism’s ability to capture our act’s ineffably layered experiences.

Surf publishing’s tradition of idiosyncratic, esoteric, cosmic-tinged reportage was at high whine during the early 1970s. Pezman embraced all of that, then moved forward into each new surfing micro-epoch. Always keeping in mind the purist appeal of the blue wall, he deftly transited the decades.

And whether or not you’ve had the pleasure of working with him, you nonetheless know Pezman from his half-century of writing and surf publishing. He has guided surfing’s media representation from his Surfer and The Surfer’s Journal pulpits for over 100,000 pages.

While you might not have shared the lineup with him, you’ll know his voice — that baritone, senatorial brogue — from his dozen or so appearances in those popular pre-streaming surf documentaries circa 2004: the head-and-shoulders framing; the bright, 90s-hangover lighting; a chyron name-plate centered lower frame.

Pez, as everyone calls him, would thereby wax eloquent, dropping gift-wrapped musings defining his impressions of the act.

“Dancers on a liquid stage” and the like.

But don’t let the Zen Kabuki fool you. To anyone who really knows him, he’s more Shakespeare’s Hal than Bodhisattva-manqué: quick witted, off the cuff, generous with a pour (and when receiving same), and endlessly flexible.

That’s not to say he doesn’t reach for the cosmos.

His inclination and gift for the metaphorical space has always had twin effects. It separates surfing from terrestrial sporting life, playing into our belief that riding storm-born bands of invisible energy, leaving nothing behind, separates surfing from, say, stock-car racing.

Next, it gives surfers license to feel slightly superior, like we’re allowed access to some pirate radio channel scrambled for all but the experienced.

This stance undoubtedly has its roots in Pezman’s come-up in the 50s. Surfing then was viewed as a teenage dance craze, its cherry-Coke-addled, hormonal participants doing the Frug to the reverb-tanked twerp pop of Jan and Dean.

At this early juncture, meager shrift was given to the ride itself. That would have irked Pezman, and any other surfer of the time. Parents, bosses, judges, and juries would not sit still to hear of surfing’s incalculable natural gifts. The tee-vee showed them all they needed to see.

And so, surfing could have gone hopelessly pop. Contests, gossip, hullabaloo. (No offence, almost every online surf mag in 2021.)

Pezman chose a different route, one marked by literature, art, and custodially aware language. Advocating for vastly skilled watermen living on the fringes. Pacing in a solid dose of pure, empty wave energy. The odd hit of underground-broadsheet hippie rap.

This last bit of lingua franca was a product of the times and to modern ears can sound almost quaint. Even that indulgence tended to smoke his competition. Imagine where it could have gone if it had landed in other, more booster-ish, stewardship.

As ever, tone-deaf, clout-hungry forces with more spreadsheet chops than taste attempt to stamp surfing with their mercantile prerogatives.

The barn door has been blown off its hinges.

“The Secret Thrill” is now so oversubscribed, TikTok atomized, and mass media that any claim surfing once had as a pursuit for outsiders, an outpost of post-Beat hip- ness — whether or not such a claim truly held water — is more or less a canard.

This volume of Pezman miscellany serves to show the author’s steady hand, his self-knowledge as well as his molecular — say it! — cosmic understanding of everything surf.

Once we remove all of the crêpe we hang on surfing — that’s another “Pez Says” — all that’s left is the ride.

And, blessedly, the ride is enough.