Want to feed that inquisitive, wonderful mine o' yours?

There isn’t a magazine in the world that can touch The New Yorker. Nineties years in the biz (started in 1925), this small paper magazine of one hundred pages or thereabouts has the ability to make the dullest subject, car recalls, say, and turn it into the most compelling and educating thing that has touched your eyes since, yeah, the last New Yorker feature you read.

And the thing about The New Yorker is… it never gets old. Despite a rigid house style, the stories sing.

In the June 1 issue, we get personal history piece Off Diamond Head by William Finnegan. Has there been a better account of a kid finding his way in the ocean than this? Moves to Hawaii from California ’cause his dad gets a gig as a production manager on a Hawaiian musical variety show. Day one, the kid grabs his board and looks for waves.

Here’s an excerpt…

I ran to the beach for a first, frantic survey of the local waters. The setup was confusing. Waves broke here and there along the outer edge of a mossy, exposed reef. All that coral worried me. It was infamously sharp. Then I spotted, well off to the west, and rather far out at sea, a familiar minuet of stick figures, rising and falling, backlit by the afternoon sun. Surfers! I ran back up the lane. Everyone at the house was busy unpacking and fighting over beds. I threw on a pair of trunks, grabbed my surfboard, and left without a word…

…Nothing was what I’d expected. In the mags, Hawaiian waves were always big and, in the color shots, ranged from a deep, mid-ocean blue to a pale, impossible turquoise. The wind was always offshore (blowing from land to sea, ideal for surfing), and the breaks themselves were the Olympian playgrounds of the gods: Sunset Beach, the Banzai Pipeline, Makaha, Ala Moana, Waimea Bay.

All that seemed worlds away from the sea in front of our new house. Even Waikiki, known for its beginner breaks and tourist crowds, was over on the far side of Diamond Head—the glamorous western side—along with every other part of Honolulu anybody had heard of. We were on the mountain’s southeast side, down in a little saddle of sloping, shady beachfront west of Black Point. The beach was just a patch of damp sand, narrow and empty.

I paddled west along a shallow lagoon, staying close to the shore, for half a mile. The beach houses ended, and the steep, brushy base of Diamond Head itself took their place across the sand. Then the reef on my left fell away, revealing a wide channel—deeper water, where no waves broke—and, beyond the channel, ten or twelve surfers riding a scatter of dark, chest-high peaks in a moderate onshore wind. I paddled slowly toward the lineup—the wave-catching zone—taking a roundabout route, studying every ride.

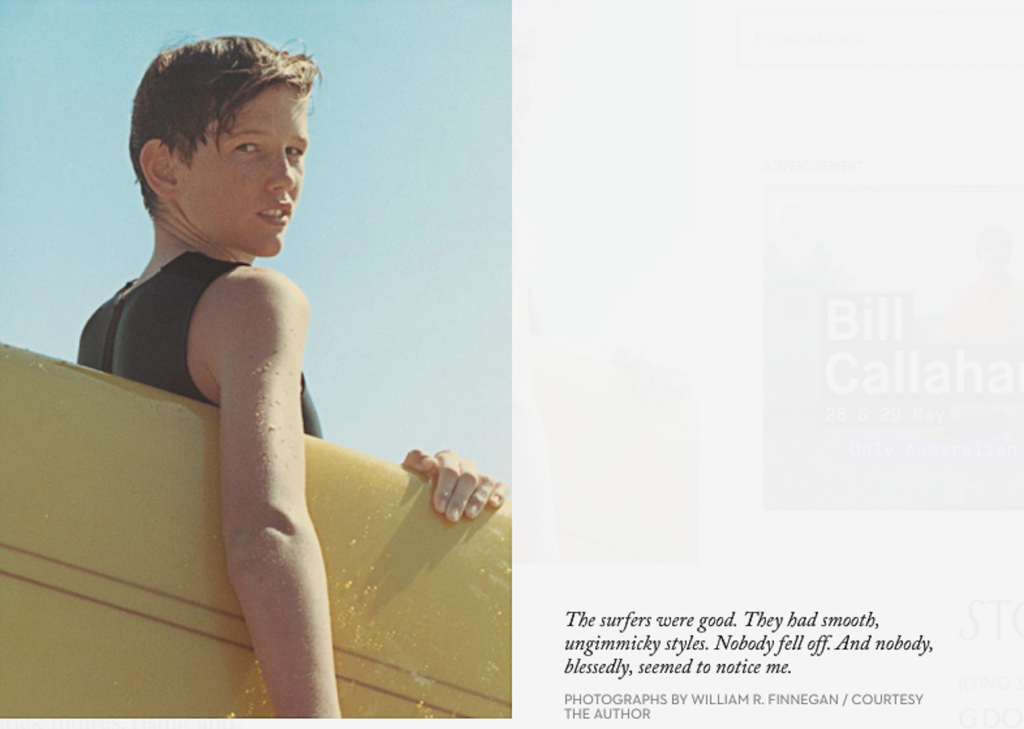

The surfers were good. They had smooth, ungimmicky styles. Nobody fell off. And nobody, blessedly, seemed to notice me. I circled around, then edged into an unpopulated stretch of the lineup. There were plenty of waves. The takeoffs were crumbling but easy. Letting muscle memory take over, I caught and rode a couple of small, mushy rights. The waves were different—but not too different—from the ones I’d known in California. They were shifty but not intimidating. I could see coral on the bottom but nothing too shallow.

There was a lot of talk and laughter among the other surfers. Eavesdropping, I couldn’t understand a word. They were probably speaking pidgin. I had read about pidgin in James Michener’s “Hawaii,” but I hadn’t actually heard any yet. Or maybe it was some foreign language. I was the only haole (white person—another word from Michener) in the water. At one point, an older guy paddling past me gestured seaward and said, “Outside.” It was the only word spoken to me that day. And he was right: an outside set was approaching, the biggest of the afternoon, and I was grateful to have been warned.

As the sun dropped, the crowd thinned. I tried to see where people went. Most seemed to take a steep path up the mountainside to Diamond Head Road, their pale boards, carried on their heads, moving steadily, skeg first, through the switchbacks. I caught a final wave, rode it into the shallows, and began the long paddle home through the lagoon. Lights were on in the houses now. The air was cooler, the shadows blue-black under the coconut palms. I was aglow with my good fortune. I just wished I had someone to tell: “I’m in Hawaii! Surfing in Hawaii!” Then it occurred to me that I didn’t even know the name of the place I’d surfed.

It was called Cliffs. It was a patchwork arc of reefs that ran south and west for half a mile from the channel where I first paddled out. To learn any new spot in surfing, you first bring to bear your knowledge of other breaks—all the other waves you’ve learned to read closely. But at that stage my archives consisted of ten or fifteen California spots, and only one that I really knew well: a cobblestone point in Ventura. And none of this experience especially prepared me for Cliffs, which, after that initial session, I tried to surf twice a day.

It was an unusually consistent spot, in the sense that there were nearly always waves to ride, even in what I came to understand was the off season for Oahu’s South Shore. The reefs off Diamond Head are at the southern extremity of the island, and thus pick up every scrap of passing swell. But they also catch a lot of wind, including local williwaws off the slopes of the crater, and the wind, along with the vast jigsaw expanse of the reef and the swells arriving from many different points of the compass, combined to produce constantly changing conditions that, in a paradox I didn’t appreciate at the time, amounted to a rowdy, hourly refutation of the notion of consistency. Cliffs possessed a moody complexity beyond anything I had known.

Mornings were especially confounding. To squeeze in a surf before school, I had to be out there by daybreak. In my narrow experience, the sea was supposed to be glassy at dawn. In coastal California, early mornings are usually windless. Not so, apparently, in the tropics. Certainly not at Cliffs. At sunrise, the trade winds often blew hard. Palm fronds thrashed overhead as I tripped down the lane, board on my head, and from the seafront I could see whitecaps outside, beyond the reef, spilling east to west on a royal-blue ocean. The trades were said to be northeasterlies, which in theory was not a bad direction, for a south-facing coast, but somehow they were always sideshore at Cliffs, and strong enough to ruin most spots from that angle.

And yet the place had a growling durability that left it ridable even in those battered conditions. Almost no one else surfed it in the early morning, which made it a good time to explore the main takeoff area. I began to learn the tricky, fast, shallow sections, and the soft spots where a quick cutback was needed to keep a ride going. Even on a waist-high, blown-out day, it was possible to milk certain waves for long, improvised, thoroughly satisfying rides. The reef had a thousand quirks, which changed quickly with the tide. And when the inshore channel began to turn a milky turquoise—a color not unlike some of the Hawaiian fantasy waves in the mags—it meant, I came to know, that the sun had risen to the point where I should head in for breakfast. If the tide was extra low, leaving the lagoon too shallow to paddle, I learned to allow more time for trudging home on the soft, coarse sand, struggling to keep my board’s nose pointed into the wind.

Afternoons were a different story. The wind was lighter, the sea less seasick, and there were other people surfing. Cliffs had a crew of regulars. After a few sessions, I could recognize some of them. At the mainland spots I knew, there was usually a limited supply of waves, a lot of jockeying for position, and a strictly observed pecking order. A youngster, certainly one lacking allies, such as an older brother, needed to be careful not to cross, even inadvertently, any local big dogs. But at Cliffs there was so much room to spread out, so many empty peaks breaking off to the west of the main takeoff—or, if you kept an eye out, perhaps on an inside shelf that had quietly started to work—that I felt free to pursue my explorations of the margins. Nobody bothered me. Nobody vibed me. It was the opposite of my life at school.

I had never thought of myself as a sheltered child. Still, Kaimuki Intermediate School was a shock. I was in the eighth grade, and most of my new schoolmates were “drug addicts, glue sniffers, and hoods”—or so I wrote to a friend back in Los Angeles. That wasn’t true. What was true was that haoles were a tiny and unpopular minority at Kaimuki. The “natives,” as I called them, seemed to dislike us particularly. This was unnerving, because many of the Hawaiians were, for junior-high kids, quite large, and the word was that they liked to fight. Asians were the school’s most sizable ethnic group, though in those first weeks I didn’t know enough to distinguish among Japanese and Chinese and Korean kids, let alone the stereotypes through which each group viewed the others. Nor did I note the existence of other important tribes, such as the Filipinos, the Samoans, or the Portuguese (not considered haole), nor all the kids of mixed ethnic background. I probably even thought the big guy in wood shop who immediately took a sadistic interest in me was Hawaiian.

He wore shiny black shoes with long, sharp toes, tight pants, and bright flowered shirts. His kinky hair was cut in a pompadour, and he looked as if he had been shaving since birth. He rarely spoke, and then only in a pidgin that was unintelligible to me. He was some kind of junior mobster, clearly years behind his original class, just biding his time until he could drop out. His name was Freitas—I never heard a first name—but he didn’t seem to be related to the Freitas clan, a vast family with several rambunctious boys at Kaimuki Intermediate. The stiletto-toed Freitas studied me frankly for a few days, making me increasingly nervous, and then began to conduct little assaults on my self-possession, softly bumping my elbow, for example, while I concentrated over a saw cut on my half-built shoeshine box.

I was too scared to say anything, and he never said a word to me. That seemed to be part of the fun. Then he settled on a crude but ingenious amusement for passing those periods when we had to sit in chairs in the classroom section of the shop. He would sit behind me and, whenever the teacher had his back turned, hit me on the head with a two-by-four. Bonk . . . bonk . . . bonk, a nice steady rhythm, always with enough of a pause between blows to allow me brief hope that there might not be another. I couldn’t understand why the teacher didn’t hear all these unauthorized, resonating clonks. They were loud enough to attract the attention of our classmates, who seemed to find Freitas’s little ritual fascinating. Inside my head the blows were, of course, bone-rattling explosions. Freitas used a fairly long board—five or six feet—and he never hit too hard, which permitted him to pound away without leaving marks, and to do it from a certain rarefied, even meditative distance, which added, I imagine, to the fascination of the performance.

I wonder if, had some other kid been targeted, I would have been as passive as my classmates were. Probably. The teacher was off in his own world, worried only about his table saws. I did nothing in my own defense. While I eventually understood that Freitas wasn’t Hawaiian, I must have figured that I just had to take the abuse. I was, after all, skinny and haole and had no friends.

(Continue reading here)