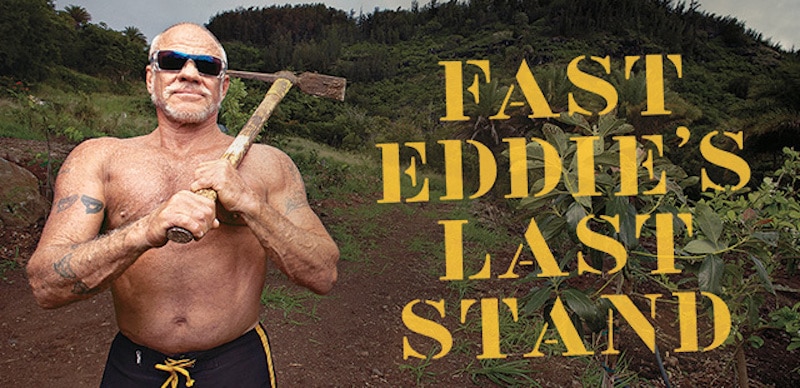

Eddie Rothman vs. Monsanto!

Three years ago I traveled to Oahu to write

a story for Playboy on Eddie Rothman’s fight against biotech giant

Monstanto. Writing about Da Hui yesterday made me remember that

time fondly. It is a very long read but it is Sunday, in America.

What else are you going to do until the Golden State Warriors tip

off against the Cleveland Cavaliers?

(First printed in Playboy. July 2013)

Fast Eddie Rothman is standing on the front

deck of his perfectly tropical Oahu house, blocking the perfectly

temperate 75-degree sun, waiting for me. His hands, gnarled and

scarred with the memories of many teeth, are balled up into tight

fists and he drums the deck’s railing.

His fists have drummed often. There was the time they drummed

the teeth out of the big Australian surfer’s mouth. There was the

time they slapped the vice president of a major surf brand 11 times

for bald-faced lying. There was the time they bashed the head of a

pervert jacking off in the tropical bushes near the bike path. Or,

wait—those weren’t his hands proper, those were his hands gripping

a piece of rebar. There was the time they landed repeatedly on the

sunburned cheek of a man who had partnered with a local podiatrist

to smuggle pain pills by strapping them to children. This man

threatened to blow up Rothman’s house with a grenade and bounced

his secretary’s head off a rock wall. Rothman gave him a drumming

so solid that the man spent a week in the hospital, because like

the Australian surfers, surf-brand vice presidents and perverts

before him, he had it fucking coming.

Oahu, the most mythical island in the Hawaiian chain, is not

commonly associated with bloody beatings and broken teeth. It has,

rather, been etched into the subconscious as an island paradise

since the turn of the 20th century, when wealthy families, inspired

by pastel-hued postcards, steamed across the sea on coconut-scented

winds and basked in its flawless climate. GIs followed on their way

to World War II’s Pacific Theater, gaped at hula girls, got lei’d

under a tropical moon and thought, Thank you, Uncle Sam. And their

sons became surfers and went in search of their fathers’ dreams.

They found them on Oahu’s North Shore, where the waves were massive

and perfect if you had the courage and skill to ride them. They

were joined by men with names such as Da Bull, Butch and Duke, and

they too etched Oahu into the subconscious. As the 1950s turned

into the 1960s, surf-ploitation films about exotic Waimea Bay and

the Banzai Pipeline became the rage, and the Beach Boys crooned

about riding the wild surf.

But the decades between then and now have been marked by immense

struggles for the men who were born into this paradise or who

arrived and never left. Men like Eddie Rothman. Today I walk down a

dead-end road not five miles north of Waimea Bay, where he is

waiting for me. I turn left and push my way into his million-dollar

beach compound. Rumors and whispers about his penchant for violence

haunt the North Shore. Brave surfers speak of him in hushed tones,

afraid they might turn around and see him standing there and then

see the darkness of a knockout.

On paper Rothman is simply a successful surf promoter and

co-founder of the surf brand Da Hui, which makes boardshorts, surf

apparel and, more recently, MMA fighting gear. But the past, as the

1960s turned into the 1970s, is when Rothman’s specter was born

dark. He is the elder statesman of Hui O He’e Nalu, or Hawaiian

Club of Wave Riders, which he formed nearly 40 years ago along with

local surfers Kawika Stant Sr., Squiddy Sanchez, Terry Ahue and

Bryan Amona. The mission of the club (from which the surf brand

later took its name) was to advocate for Hawaiian surfers on the

professional circuit and to help bring a sort of sanity to the

winter surf season, which had grown increasingly chaotic due to an

influx of foreign surfers who had watched the films, listened to

the Beach Boys and decided the North Shore was theirs. But it was

not theirs. And Da Hui taught them this by knocking the teeth out

of their mouths. During the winter of 1977, visiting surfers’ blood

ran both freely and cold, and Rothman became the embodiment of

fear.

Hawaii was never, in truth, a pastel-postcard island paradise.

Its name most likely comes from the ancient Maori word Hawaiki,

meaning “heaven” and “hell.” Early inhabitants practiced a harsh

form of governance that included human sacrifice by crushing the

victim’s bones. Captain Cook and the first European contact brought

disease that wiped out half the population. Inter-island war

followed inter-island war until wealthy American agricultural

interests convinced President William McKinley to annex Hawaii,

subjugating the locals and immigrant laborers under a feudal-like

system. Eventually there were enough locals and immigrants in the

U.S. territory to demand statehood, which was granted in 1959. And

then the surfers came, beginning a new sort of annexation until

Fast Eddie Rothman shoved his gnarled and scarred fists down their

throats.

Stories of the “black shorts,” as the members of Da Hui were

called after their austere beach uniform, beating down

disrespectful foreign surfers are still told today. But the club

has mellowed in recent years, hosting beach cleanups and preaching

the gospel of water safety for surfers and swimmers alike. And it

has been some time since Rothman’s been in the local papers for

illegal activity: In 1987 he was indicted on racketeering and drug

distribution charges, which were dismissed because of prosecutorial

misconduct. He had been in and out of jail before and has been in

and out since, but his relationship with “legality” is, again, only

ever whispered about. Few are brave enough to ask directly what it

is that he does. There are outrageous, whispered rumors that he’s

in the Hawaiian mafia, that he’s a drug dealer, that he’s a

murderer for hire. But no one really knows, because when Rothman

takes care of business his way, it quickly and quietly goes from

rumor to whisper to legend. No one questions the legend.

And he is waiting for me because I broke the rules. I wrote a

book about the North Shore that included him and his specter, which

was a severe breech, on my part, of North Shore whisper etiquette.

(Welcome to Paradise, Now Go to Hell is being published by Harper

Collins in December.) He got a copy of the unfinished manuscript

from Scott Caan, who plays today’s version of Danno on the remake

of Hawaii Five-0, and Rothman ordered me to his house.

He watches me approach from his wraparound deck, and the reality

of the man matches the whispers, even though he is 65 and only

five-foot-six if generous, five-foot-five if honest. He is roping

muscle. His arms, usually bare, are perpetually flexed. His

expression rarely changes. His pug nose has been broken more than

once. His gray hair is shaved to a fine stubble. The neck that

holds that head up is as thick as a tree. He is a testament to the

power of attitude and intention. He has bested more men than he can

count, and it looks as if I will be counted among the

multitude.

Rothman looks at me and takes me by surprise. Instead of a left

hook he drops this bomb: “If you want to tell a fucking important

story, then tell this one: Monsanto. Those fuckers are here. They

have all these experimental farms right over the hill and are

poisoning the land and poisoning the people. Write that shit.”

While my eyes had been trained on the pounding surf and the surfers

and the fighters, by Rothman’s reckoning I’d had my head in the

sand. He is asking me to turn 180 degrees and look squarely toward

the island, to those verdant hills, to where Monsanto has alighted

like so many interlopers before.

Monsanto is, of course, the multinational agricultural

biotechnology company based in St. Louis—some 5,000 miles from the

North Shore. It is the staggeringly profitable company that once

manufactured PCBs and Agent Orange but for the past 20 years has

been making genetically modified seeds that grow

herbicide-resistant crops such as soybeans, corn and sugar beets.

In Hawaii, Monsanto, along with Syngenta, DuPont Pioneer Hi-Bred,

Dow AgroSciences and BASF, is growing some 7,000 acres of crops,

including soybeans and corn. These crops are not intended for human

consumption per se; rather they are seed crops that will be shipped

to farmers worldwide to plant in their fields to sell on the open

market. Much of it ends up as feed for livestock in countries

around the world. While international farmers have become dependent

on Monsanto’s incredibly effective Roundup Ready seed and Roundup

herbicide, Rothman is part of a growing group of Hawaiians who see

this as yet another encroachment on their beloved land.

His take on them is quite simple: “They are greedy fucks. They

don’t care about anything but making money, and they are doing it

all right here on Oahu and all over the islands—threatening

farmers, closing the local people down, closing farmers’ markets.

You know, if some of their GMO seed blows on someone’s land, then

they own it. They are controlling our politicians too. Laws to

label food as GMO have come into our Congress, but they get shut

down. They are taking over the land, just like in the past.”

And his rant continues as he lists past wrongs on Hawaii—the

early explorers bringing diseases to the islands, the Mormons

bringing Mormonism, the sugar barons overthrowing the Hawaiian

monarchy and enslaving the people, foreign surfers coming and

stealing the waves, the methamphetamine epidemic now engulfing the

islands. He eventually brings it back to Monsanto. “And now they

are fucking with our food. They are fucking with the very root of

who we are as people. It’s the worst thing they could be doing.

Greedy fucking fucks. For what? For money? Money does strange

things to people. Fuck them.”

I’d never heard him talk about anything with such passion other

than Hawaiian wave sovereignty, the notion that these are their

waves, to be surfed their way. With Monsanto, as with everything,

Rothman goes with his gut.

“They got all these research farms right over the hill from my

house,” says Rothman. “We’re having a March Against Monsanto in

Hale’iwa tomorrow.” He grinds me with his eyes and it is completely

expected that I will show up.

The next day I drive up the volcanic range that bisects the

island and toward the protest march in Hale’iwa. I pass the silly

Dole Plantation tourist trap where the fruit company grows

pineapple only for show. After a century of dominance on the

islands, pineapples are now grown cheaper and more efficiently in

Costa Rica. I drive past land that used to be sugarcane as far as

the eye can see. But sugarcane is produced cheaper and more

efficiently in Brazil these days. Pineapple and sugarcane fields,

now deserted, are the ghosts of agribusinesses that once ruled

virtually every part of Hawaiian life. The barons used the islands

as personal piggy banks, caring little for the ecosystem or the

local population. And just as I drop down the other volcanic side,

the North Shore splayed before me, I see a street sign that reads

Adopt a highway, Litter control next two miles: Monsanto

Company.

Monsanto was drawn to Hawaii for some of the same reasons that

attracted the pineapple and sugar interests, namely its nutritious

volcanic soil and its perfect, perpetually 75-degree weather. The

islands are like a giant greenhouse. On the mainland most crops

have one growing season, maybe two. In Hawaii they can have up to

four, which suits Monsanto’s purposes. More harvest cycles mean

more seeds, and large tracts of land have been opened on Oahu,

Maui, Kauai and Molokai to meet the seed demands of the world’s

farmers. These demands have made the seed industry Hawaii’s largest

agricultural sector. Worth more than $240 million, it is

responsible for a third of Hawaii’s agricultural income. While

valuable to Hawaii’s fragile, tourism-heavy economy, the income

does little to settle the apprehensions of men like Eddie

Rothman.

And Rothman is not alone, not by far. When I exit the main road

toward Hale’iwa, hundreds of protesters have already grouped

together near the 7-Eleven at the south end of town, or the

“bottom” as it is called. It’s a motley bunch: moms pushing

strollers, old people with canes, chunky white transplants in awful

denim shorts, surfers, Japanese tourists, dreadlocked hippies

banging on ukuleles, girls in bikinis, tough mokes. Moke is

Hawaiian slang for an aggressive “braddah” who wears “da rubba

slippas” and punches haoles. Haole is Hawaiian slang for “white

man.” Everyone has a sign with some variation on the demand that

Monsanto leave Hawaii. Pit bulls roam freely. A man wearing a V for

Vendetta mask tells a man with a head as big as a Fiat, “Look at

those clouds, brah. I hope they don’t chemtrail us.” It is a widely

held belief here that Monsanto dumps heavy metals into the clouds

in order to control the weather. As expected, Monsanto denies the

protesters’ claims, of chemtrailing and otherwise.

Across the parking lot a giant pickup truck draped in Hawaiian

flags is surrounded by men wearing red Da Hui T-shirts. There is

Kala Alexander, a surfer and actor who became famous as the

unlikely star of a series of YouTube videos featuring the beatdowns

he gave surfers who showed disrespect in the waves. Those videos

are a relic of his past. Alexander’s most recent activist star turn

is as a concerned citizen speaking out against the encroachments of

the biotech companies in a documentary about GMOs and Hawaii.

Rothman stands with the protesters, arms folded across his chest

like a sentinel, and lets the others do the talking. As I approach,

he says, “You gotta meet the guys who started the march,” and walks

me over to two men busily directing the proceedings. “These are the

real people. These are the ones changing shit.”

One of them is Dustin Barca, a professional surfer and also an

MMA fighter from Kauai. He is handsome, with severely cauliflowered

ears. “Five years ago I started studying, reading, watching the

movies about GMOs,” he says. “I wanted to get my facts straight

before acting. I learned how damaging they are to the people and to

the land. It is poison. And so now I want to build awareness. I

want to educate the local people on what is happening. I’m not

interested in saving the world. I’m interested in saving my

island.”

Rarely is a word spoken here today that isn’t rooted in fierce

localism. Walter Ritte, standing next to Barca, nods his head in

approval. Ritte, older and slight with a full gray beard, is from

Molokai and is a legend among Hawaiian activists. His involvement

in the GMO debate is tied to the University of Hawaii’s genetic

experiments with taro, a traditional Hawaiian root. “Taro is a

family member for Hawaiians,” he told me. “It is our firstborn. If

they’re going to mess with our firstborn then they’re going to mess

with us. This whole GMO issue is so complicated, and I like to make

it simple. Basically GMOs package us, they own us. And I would like

to tell them—the companies—if you hurt our culture and you hurt our

land, you’re in for trouble.”

In days past, Da Hui would have brought the trouble immediately

and violently on the interlopers, but today its members have signs

and slogans and bullhorns. They are joined in solidarity with

farmers and other citizens, joined not by surfing but by living in

and loving Hawaii. The march begins, and the energized crowd

chants, “Thanks for visiting. Now go home like the rest of the

tourists!” People fill the Kamehameha Highway, smiling, chanting

and trading horror stories about the evils of GMOs and “Mon-Satan.”

I hear many stories about a Monsanto property on Oahu called the

Kunia research farm. People say fish DNA is put into strawberries

there and 70 different kinds of chemicals are used on the crops.

They say Monsanto is destroying Hawaii’s native species by making

Frankencrops that cross-pollinate with everything. They say the

farm is killing all the bees and changing the weather, and that it

isn’t from here. They say the farm does not belong here.

There was a time when Rothman was the interloper, the unknown

quantity on the North Shore. Although many people assume he is

Hawaiian, he was born Jewish in Philadelphia. “I don’t know nothing

about Jew stuff, but once this lady on the North Shore made me some

Jew food and it was good,” he tells me. He has said that his mother

physically abused him as a boy. Eventually she left, and his father

moved to Long Beach, California with him. “My father would fucking

beat the shit out of me because I was little, and that made him

mad.” Eventually Eddie’d had enough. When he was 14 years old he

stole enough money out of his father’s wallet for a one-way ticket

to Honolulu. He had surfed in California and had seen the

surf-ploitation films featuring Hawaii, with its perfect giant

waves, palm trees, white sand and easy smiles.

He landed in Honolulu knowing no one. He knew only that

something felt almost right. He stayed in Honolulu for a few years,

flying to southern California to pick up marijuana and bring it

back to Hawaii. He briefly went to school in Long Beach. “I went to

school a couple of times, but the school told me if I didn’t show

up, they would pass me.” He eventually moved permanently to the

North Shore. It had everything he needed: surf, sun, a market for

his marijuana. And as a 16-year-old he would get by selling it and

stealing cars.

One bright day he was in the bushes at the Sunset, one of the

North Shore’s famous wave breaks, breaking into cars, when he ran

into a pack of Hawaiian locals who were doing the same thing. How

did they come to accept this unlikely outsider? “I don’t talk

good,” says Rothman. “I have bad speech like them, so it was easy,

and everything went from there. I sounded like them, and they just

accepted that I was like them.” He was tenacious, so they flew him

around the islands to crack heads for such offenses as not paying

debts within an appropriate time. When I suggest that the tough

Hawaiians had adopted him, he bristles. “They didn’t adopt shit. I

proved myself every fucking day. I proved myself with these.”

Again, he holds up a fist. A scarred, tooth-nicked fist. On the

North Shore, not speaking well goes only so far.

Of all the enemies Rothman has faced over the years, Monsanto is

by far the biggest and most elusive. Bloomberg reports that the

company did $5.47 billion in revenue in this year’s second quarter

alone. It, along with the other seed companies, owns or leases

25,000 acres on the islands.

Before arriving in Hawaii, Monsanto had perfected its craft.

Company scientists were among the first to genetically modify a

plant cell in their laboratories, and they knew they had struck

gold. Traditional seeds cannot be patented, since they occur

naturally. Genetically modified seed, on the other hand, can be, as

ruled by the U.S. Supreme Court. The company realized it could make

a higher-yielding, more-rugged product through science, and it

could better monetize that product by applying patent law. And

Monsanto protects these patents fiercely, suing any farmer who

dares replant instead of purchasing. The company argues that it has

spent billions of dollars perfecting these seeds and it only makes

sense to recoup investment costs. The Supreme Court agrees. In May,

the Court ruled that farmers are not allowed to replant Monsanto

seed but must repurchase yearly. To many farmers, Roundup’s near

silver-bullet-like effectiveness is worth the cost. Still, Rothman

takes issue with this, seeing it as a form of extortion. Just as

offensive to him is how close Monsanto is to his home. How it looms

in his backyard. “That farm is fucking evil,” he adds to the

chorus, near the end of the march.

“That farm” is the Kunia research farm, which sits just opposite

the volcanic mountain range from the North Shore, halfway up a

small, shack-lined road. It is unassuming from the outside. A man

wearing a Jurassic Park-looking uniform lets me in through the

gate, and I am introduced to two scientist-farmers who take me on a

tour of the property. The farm is virtually all corn and soybean,

and as we drive for hours they point out the sustainability of the

operation: the terraces, the drip irrigation. They show me an area

that has been donated to small-scale local farmers who grow produce

there, some of it organic, to sell at farmers’ markets. It’s not a

nightmare factory out of The X Files. It is the picture of American

ingenuity, but American ingenuity is not the Hawaiian dream.

When I raise the protesters’ concerns about cross-pollination

destroying native species, Monsanto representatives point out that

corn doesn’t cross-pollinate with anything on the islands and has

no relatives here, so there’s no danger. Even if crosspollination

isn’t a worry, pesticide runoff still plagues Hawaii. Oahu has its

pineapple and sugarcane ghosts. Researchers from Stanford, the

University of California and the University of Hawaii have reported

on pesticides in the groundwater and fragile reefs damaged by

pesticide runoff after decades of largely unregulated rule by big

agricultural interests on the island.

But that’s not Monsanto’s past here in Hawaii, and the company

claims to be dedicated to custodianship of the land. The company

tells me it pulls up and recycles truckloads of plastic from old

pineapple fields. But in many Hawaiian eyes—in Rothman’s eyes—there

is no difference between the past and the present, which directly

affects Hawaiian protesters’ feelings regarding science. Hawaiians

were told in the past that the pesticides used on pineapples were

good and that DDT spraying to control mosquitoes was good. They,

even more than the mainland America population, are loath to

believe the science is sound. Critics such as Michael Hansen,

senior staff scientist for Consumer Reports, help feed the

perception that GMOs are poison. He says, “We now have allergy

problems from genetic modification, or adverse effects on bone

marrow, liver, kidney and reproductive systems. There have been

animal studies, but they need to be followed up on. There is just

no control.”

GMO proponents scoff at the lack of scientific rigor on the

other side. After I leave the farm I speak with Alison Van

Eenennaam, a specialist in animal genomics and biotechnology in the

Department of Animal Science at the University of California,

Davis. She says, “As a scientist, I don’t just get to have a bad

feeling about something. There have been 15 years of research, more

than 400 scientific studies, and we’ve eaten more than 3 trillion

meals. The jury is absolutely in. The overwhelming bulk of the data

says there is nothing biologically different in genetically

modified food. We eat it. We digest it. It breaks down. It turns

into us. In fact, it is a criminal injustice for us not to feed the

world with these products, especially in countries where people are

dying of starvation instead of obesity. It is morally

bankrupt.”

But if there’s anything Rothman doesn’t lack, it is moral

outrage. He’s outraged at a company that has essentially patented

nature for profit. He’s outraged at technology that has given rise

to Roundupresistant weeds that have forced farmers across the

country to revert to using more toxic chemicals to protect their

crops. Rothman’s distrust is a portion of America’s writ large. For

a citizen, the first step toward truth often begins with “just

getting to have a bad feeling about something.” And Rothman’s bad

feeling is about yet another threat to his vision of the Hawaiian

dream. It is about defending his version of the pastel-postcard

Miltonian paradise. Oahu is still an island in the middle of the

ocean. It still has coconut-scented winds and waves so big and

ideal that none have ever been found bigger or better. And he wants

to keep it pure. And this dream, even if never true, dies hard.

Rothman is smoldering when I go back to his house after visiting

the farm. The sun is well into its downward slide, painting the

firmament with soft oranges and fiery pinks. His shoulders, as big

as hills, slump. He seems exhausted. We stand quietly for a minute,

watching the ocean. It’s hard not to think this is essentially

about Monsanto interlopers coming in and rewriting the rules of the

island. Like the foreign surfers before them and Captain Cook

before them. And it’s hard not to see that Rothman doesn’t know

exactly what to do.

As if to comfort himself, he recounts a moral victory in his

past, over an enemy he could physically best. “See that right

there?” he says, pointing to a spot on the beach. I nod. “Years ago

there were some little girls playing on the sand, and this big guy

came and, you know, showed them his…you know…his thing.” He

gestures at his crotch. “So I went over to his house. He was a big

guy, and he was in there cleaning his gun, so I got scared. But I

knocked on the door and he answered, and then he made a move. I’ve

always been a little guy, and so I just go on instinct and—pow—I

hit him in the mouth. He knocked out but woke back up when he hit

the ground and started moaning. His wife came running to the door,

and they called the cops because I broke his jaw. But when the cops

came they couldn’t say nothing because the guy would have to say

why I cracked him. He was a lieutenant in the Army or some shit.

Fucking creep. But that’s the last time he showed himself to any

kids.” He lowers his head and rubs his eyes.

“Why don’t you just crack them?” I ask, referring to Monsanto.

This is exactly how Rothman drove the surf world into a panicked

fear, by knocking enough people out that no surfer ever steps out

of line. He turns toward me, and his expression that rarely changes

turns into a mask of helpless bewilderment. “I can’t,” he says.

“There is no them. I mean, they are everywhere. If I go and slap

someone, they just gonna throw me in jail, and I don’t even know

who they are. They hide behind their corporation.” He looks back

out at the Pacific. The sun is even lower now, and the orange is

softer, the pink more fiery. He sighs deeply, carrying the weight

of his own legend and facing a new foe that is far baser than any

he has faced before. He wants to act, but how? He sighs again and

growls, “Let’s go.”

We drive together in silence down his dead-end road, out to the

main Kamehameha Highway, then quickly turn into a gorgeous piece of

unspoiled North Shore greenery. The land is terraced where we are

standing, and I can see half-dug rows almost ready for planting. A

large yellow tractor sits idle. The volcanic range rises in the

near distance and is crowned with a strange sort of pine that I

have seen only in Hawaii. “This is my farm,” he says as we start

moving toward the patch of reddish dirt that is his organic

farm.

Eddie Rothman the specter has become Eddie Rothman the farmer,

just on the opposite side of the range from where Monsanto’s Kunia

research farm sits. He tells me he spends long days moving giant

rocks by hand, because if he used the tractors they would “fuck up

all the water hoses we have.” He tends to taro crops and digs holes

for water-purification systems by hand as well. “I’ve seen them do

it this way in Samoa. They use their hands and their feet like

this.…” He climbs down into an unfinished hole and starts to claw

at the earth. He digs his own wells, installs solar panels and

feeds his chickens and ducks.

Rothman becomes more animated and less exhausted as we wander

around his farm—this plot of land is a Hawaii he can control, where

no outsiders threaten the balance he’s struggling to regain. He

tells me he worries about Monsanto’s chemical drift but is doing

everything in his power to limit his farm’s exposure to the

company’s tactics. He says the farmwork is good for his body, and

the food, once it really starts growing, will be good too. As we

walk, it becomes clear that farming is the way he has chosen to

physically go to war against Monsanto, by taking back the land,

acre by acre. It’s a tactic shared by other, more experienced

farmers in Hawaii, who are lobbying the largest landowners to shift

their proportion of GMO leases toward more natural and organic

farmland. They want land tainted by pesticide use to be cleaned and

repurposed as incubators and education centers for organic farming.

They want to be given a fighting chance to sustain their island

their way. The chances that a few organic farmers in the middle of

the ocean will evict a billion-dollar multinational corporation are

slim. But Rothman will have none of that.

Hawaii has been decimated by foreign disease, subjugated by

foreign agricultural interests, annexed by foreign nations. It is a

series of defeats. Rothman, though, has a victory to his name.

Because of Da Hui, and because of him, visiting surfers’ blood

still runs cold. He wrestled and punched the North Shore back from

the clutches of foreign surf interests, and he is dead set on doing

the same for the land. He has played slim odds in the defense of a

dream before and won.

He also has the land on his side. The locals talk about the

curse of Pele, the legend that anything taken from the Hawaiian

Islands will bring bad luck to the taker. By that reckoning,

Monsanto is exporting a bête noire as its seeds get planted around

the world. Whether because of a curse or the passing of time, the

sugarcane and pineapple barons have come and gone. Captain Cook is

dead. The interlopers in Hawaii have gotten their due. Eddie

Rothman is doing what he can, by protest and by pitchfork, to hurry

it along. Before we get into his truck and head back down the hill,

he kicks at a volcanic rock and then gives my shoulder a hard pat.

It hurts.