Why are sharks exempt from our usual attitude towards animals?

Did you notice the spike of shark hits last week? Three attacks, one fatal. Kitesurfer killed in New Caledonia. Bodyboarder becomes a double-amputee in Reunion. A fifteen-foot white throws a surfer off his board in south-west WA while his brother screams in horror.

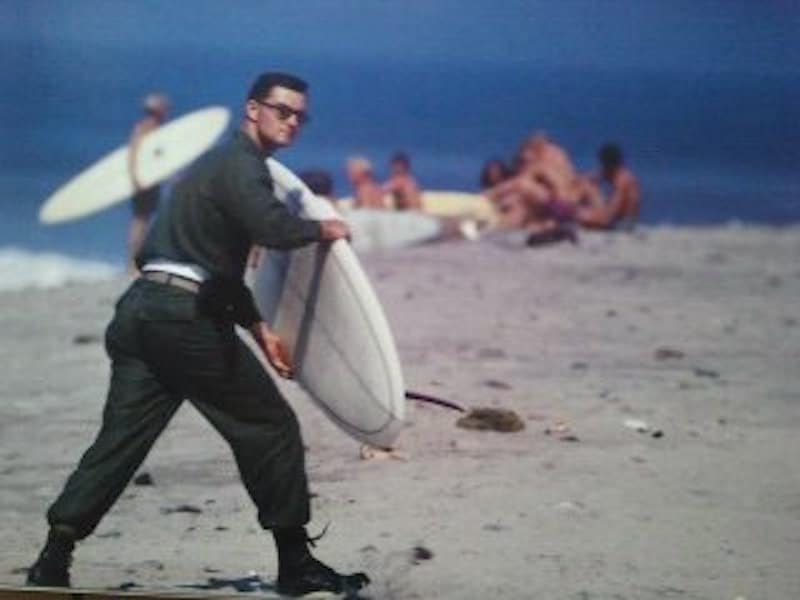

The noted writer and surfer Fred Pawle sure did.

It was like every single damn Christmas had come at once for Fred, who fearlessly, and unfashionably, has been banging the drum to treat sharks as we do other fish.

This morning, Fred wrote a piece for The Australian newspaper titled Indiscriminate killers aren’t deserving of our sympathy.

Can you guess the angle? Let’s read!

Almost everywhere one looks — the CSIRO, universities and the various departments of primary industries or fishing — one sees a higher priority given to sharks than surfers, divers or swimmers. This misanthropism springs from the common perception that humans are a blight on our planet and that a few casualties from interactions with nature are an acceptable price in the quest to save the Earth from rapacious humans. Such a deliberate lack of humanity is usually associated only with religious delusions or witchcraft. But, then, you “believe” in “saving” the environment or you don’t.

The longer this goes on, the more absurd our behaviour. In this respect, Reunion Island provides a worrying sign of where Australia is heading. Reunion introduced a marine park on the west side of the island in 2007 and implemented a ban on shark fishing. Since 2011, the effect of these policies has become apparent.

All this for … a fish. Why can’t we treat sharks like other fish, or cattle, or rats? Why are they exempt from our usual attitude towards animals? Why do we go to such pains to ensure these fish thrive at the cost of young lives?

The island has had 19 attacks in six years, seven of them fatal, from a population of 850,000. Most surfers on the island have known not just one but several friends who have been killed or badly injured. Most parents in the tight surfing community have attended the funeral of several friends’ children, if not their own.

And it was on Reunion where this week’s third attack occurred. This one encapsulates how neurotic the debate about sharks has become. A bodyboarder named Laurent Chardard arrived at Boucan Canot beach last Saturday to see, apart from large and good-quality surf, red flags on the sand.

Boucan has a 700m net around it, built last year. It is one of two netted beaches, the only places where it is considered safe to surf on an island that until recently was on every surfer’s bucket list of dream destinations. However, that morning inspectors had noticed a 2m hole in the net and erected the flags — not warning of a shark, just the potential of one.

Fifteen surfers paddled out anyway. Chardard was one of them. He was attacked by a bull shark and lost his right arm and leg. “Just let me die — I don’t want to live like this,” he told the brave fellow surfers who came to his rescue.

The day after the attack, the owner of the Petit Boucan, one of five restaurants on the beach, went on radio to complain he’d had almost no customers since the attack and that Chardard should be charged with a criminal offence. He also floated the idea of suing Chardard for damages. In Australia it’s common to blame the victim of a shark attack but threatening to sue one takes this antagonism to a new level.

The restaurateur has since apologised — a smart move considering his clientele consists mostly of surfers, who angrily proposed a prolonged boycott. However, the restaurateur’s grievance is understandable. He has a business to run and bills to pay. His restaurant is at one of the few places on the island where it was presumably safe to swim or surf. Now that beach has been stigmatised.

Arriving at this negative outcome has not been cheap for Reunion. The net at Boucan cost about $1.5 million to build (but was still damaged by one of the first large swells to hit it), and about half that a year to maintain. The island’s tourism industry has been cut dramatically. And, of course, Chardard and his family and friends have paid a heavy price.

All this for … a fish. Why can’t we treat sharks like other fish, or cattle, or rats? Why are they exempt from our usual attitude towards animals? Why do we go to such pains to ensure these fish thrive at the cost of young lives?

The usual response to these questions is that sharks are an “apex predator” and that tampering with them has a “cascading” effect that would lead to the “collapse” of the marine environment.

But a landmark report published by the West Australian Department of Fisheries this year, the result of one of the most comprehensive studies into shark movement, disputes this. The report, bearing the catchy title of Evaluation of Passive Acoustic Telemetry Approaches for Monitoring Shark Hazards Off the Coast of Western Australia, says the movement of great whites is “highly variable” and “not consistent”. So a beach visited by a great white one day might not see another for a week, or a year, or a decade. Whether the shark returns or not, the environment adapts, just as Charles Darwin explained it would more than 150 years ago.

Besides, the marine environment is less predictable than researchers lead us to believe. One would expect, for example, that the protection of great whites in South Australia would keep the population of fur seals (also protected) under control, but it hasn’t. Instead, fur seals are reaching plague proportions and are devastating the state’s fishing industry.

These outcomes are not quite as tragically counter-productive as those on Reunion but we are getting close. As part of its highly publicised $16m plan to protect surfers on the state’s north coast, the NSW government included the construction of a net, similar to the one at Boucan, at North Wall, Ballina. Local surfers told the government the plan was ludicrous and the net would be in pieces on the beach after the first big swell. The government persevered anyway, abandoning the idea after three attempts.

Five days after that plan was dropped, the government released to The Daily Telegraph details of an exciting new plan to keep sharks away from people: dropping Shark Shields, which emit electric pulses that make sharks uncomfortable, on them from drones. If this sounds like another ridiculously complex, time-consuming, expensive and ineffective idea, it’s because it is.

Do you believe that sharks deserve to be elevated above other species? Or are you of a similar frame of mind to Fred Pawle?

(And read the complete story here, if you can get past the paywall.)