Playboy magazine nails story on drugs and their role in the big-wave game…

There was a time, late-sixties through the seventies, when Playboy was…the…magazine for writers. The magazine, which avoided graphic beaver but celebrated the ski-jump teat, was better than respectable. It was hip.

In the Christmas 1968 issue, there were contributions from Truman Capote, Lawrence Durrell, James T. Farrell, Allen Ginsberg, Le Roi Jones, Arthur Miller, Henry Miller, Norman Podhoretz, Georges Simenon, Isaac Bashevis Singer, William Styron and John Updike. You get the picture.

Of course, it ain’t much now. But, occasionally, it lights up.

Remember when Chas wrote Fast Eddie’s Last Stand? And, this year, writer Peter Simek nailed a comprehensive piece on Santa Cruz and its meth culture. Which, at first glance, might make your eyes glaze.

Like, meth in Santa Cruz? That’s still a story?

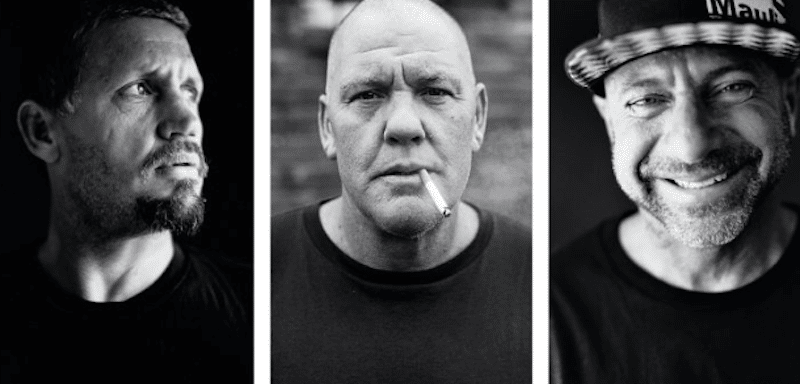

Simek’s piece, however, is a detailed run through the lives of Vince Collier, Flea Virotsko and Anthony Ruffo. The stories will make your toes curl.

Like this on Collier.

By the time he was a teenager, Collier had discovered that the Santa Cruz his dad envisioned as an idyllic childhood setting could actually be a violent arena. In the early 1970s a string of serial killers earned Santa Cruz the moniker “murder capital of the world.” There were stories of parks haunted by massacred Native Americans, of Victorian homes occupied by the ghosts of murdered brides. Perhaps it’s the fog or the silence of the redwood forests, but the town has long inspired horror, from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho to the 1987 vampire teen cult classic The Lost Boys.

From his bedroom, Collier could see the lighthouse that kept watch over Steamer Lane, a surf spot where locals hunted for waves in packs. Surfing the Lane required following a strict pecking order. Those who stepped out of line often found themselves the victims of violence. One day Collier rode a wave he wasn’t supposed to, and an older surfer tore his new wet suit. Collier hated being bullied on his home turf. He retrieved a baseball bat from his garage, and when the surfer came up from the water, Collier hurled the bat at his head, sending the man tumbling back down the cliff.

The bat incident became Santa Cruz lore, marking the moment Vince Collier established himself as the alpha male of Steamer Lane. At the time, though, Collier was scared to death. He had nearly killed a man and didn’t know what kind of retribution that would bring. Collier sought out Joey Thomas, a respected surfer and surfboard shaper who, after arriving in Santa Cruz in the late 1960s, quickly realized he needed to learn martial arts. But Collier was going to need more than a friend with a black belt; if he really wanted protection, Thomas told him, he should go up the mountain to see a man who went by the name of Jeff Ayers.

Ayers was known around town as a biker, someone who operated on the periphery of the scene. The few surfers who knew Ayers describe him as a megalomaniacal charlatan, a chameleon with a closet full of interchangeable costumes—carpenter, fisherman, businessman—that fit his various purposes. He looked like a cross between Jack Lemmon and Jack Nicholson and had charisma that could “direct traffic.”

“Everybody feared Ayers,” says Anthony Ruffo, a former pro surfer who is a few years younger than Collier. “He was fucking crazy.”

Collier and Thomas went up the hill to meet Ayers at his ranch compound north of Capitola. As they approached, stepping through a cluster of cars and motorcycles, Ayers’s dog rushed Collier and bit his leg, drawing blood. Ayers laughed.

“I want you to go up to my house,” Ayers said.

Collier scowled.

“You better go up there,” Collier remembers Thomas telling him. “He’s going to help you out.”

In Ayers’s house, Collier found many things to impress an aggressive teenager’s fitful imagination: gym equipment, guns, drugs. Ayers gave Collier marijuana and hash to smoke and sell, and taught him how to fight, shoot guns and clean and assemble weapons blindfolded. In the middle of the night he took the teenage surfer out into the bay, where mysterious schooners emerged from the thick fog, swung their davits out over the deck and dropped 150- to 200-pound bales of Thai weed. Ayers and Collier packed the marijuana into ice chests and covered it with store-bought salmon.

The other surfers at the Lane grew to fear Collier. He could now surf any wave he wanted. With his square, bulky body, Collier wasn’t built like a surfer, but he attacked waves like a bull. Along with his unlikely best friend, Richard Schmidt, a quiet and mild-mannered surfer with a distinctive bushy blond mustache, Collier became known as one of the best surfers in Santa Cruz. His first sponsorship came in the form of a suitcase filled with $30,000 in cash, given to him by the owner of a west-side surf shop that was a front for a marijuana-growing operation. Collier traveled to competitions and eventually made the pro circuit. In Hawaii, Schmidt’s smooth style at Sunset Beach and Collier’s penchant for beating on Australians who tried to surf their spots endeared the Santa Cruz surfers to the North Shore locals.

Back home, Ayers pulled Collier in deeper, taking him into the woods, where they tied indebted clients to trees and beat and branded them. Ayers would also tie up Collier, pour fish guts over his bare chest while laughing and then cut him loose, sending Collier into a rage. He found out Ayers was slipping him steroids and noticed he collected books about mind control.

“I was like, Fuck, this guy is brainwashing me,” Collier says.

Then one of Collier’s friends blew his brains out while high on cocaine—the same cocaine Collier sold. It was the final straw. Collier sent Ruffo up the hill with a message: He was done. For the next four years, Collier was sure Ayers was going to kill him. Collier kept a shotgun tucked under the driver’s seat of his truck and recoiled every time he heard a motorcycle engine.

“I had guns all over the place,” Collier says. “I used to sit in my tub with a cigar and a shotgun. I thought I was Clint Eastwood.”

And Ruffo talking about the high:

Ruffo says meth’s appeal was that it offered so much more than a rush. When he smoked meth, he felt good about himself—he felt like he did when he won the 1985 O’Neill Coldwater Classic or when he opened a surf magazine and saw his image frozen on a wave, framed by a crescent of whitewater spray.

“We’d call it ‘winning acid,’ or when you got a cover, we’d call it ‘cover acid’—those good, natural endorphins,” Ruffo says. “What meth does is give you that feeling.”

And Flea’s descent:

Perhaps no one was more publicly ravaged by meth than Flea. It got to where he took so many beatings at Mavericks, his friends feared every wave would be his last. At the 2008 Mavericks competition, Flea showed up late for his heat, took two disastrous wipeouts, landed the biggest wave of the day and then disappeared for the remainder of the tournament. Later that same year, exhausted and dehydrated, he fell backward off a cliff at Davenport, north of Santa Cruz. He was airlifted to a hospital in Santa Clara. When he was released, he headed up the coast to find Vince Collier.

Flea’s body was too broken to surf. He didn’t know how long it would be until he could feel Mavericks again. At Collier’s place in northern California, all Flea could do was lie around. Why hadn’t he died when he fell off the cliff? It seemed as though everyone else around him died. His uncle, whom he idolized, had recently passed away. The day he won his first Mavericks competition, his friend died of a brain aneurysm. Another friend died of cancer the following year. When Peter Davi died, Flea had to break the news to Davi’s son. And yet there he was, broken and bruised but not dead. He could think of a dozen times when he should have been killed. Once, his leash got stuck in the rocky reef at Mavericks and he took wave after wave on the head. That day, it felt like the only way he wouldn’t drown was if he found the strength to do a sit-up with a mountain pressing on his chest. And yet, his leash broke. He didn’t die.

Holed up at Collier’s, all Flea could think about was drinking and smoking meth. When he was finally able to surf again, he didn’t. Instead, he combed the beaches of Santa Cruz and bought cases of spray paint at hardware stores. Flea’s sunken, scabby face haunted the town. He was a pariah, a cautionary tale. His house, once the surf scene’s social center, became a hoarder’s den and a flophouse for meth-heads. Uncashed sponsors’ checks lay buried beneath piles of spray-painted driftwood.

Compelling, yeah?