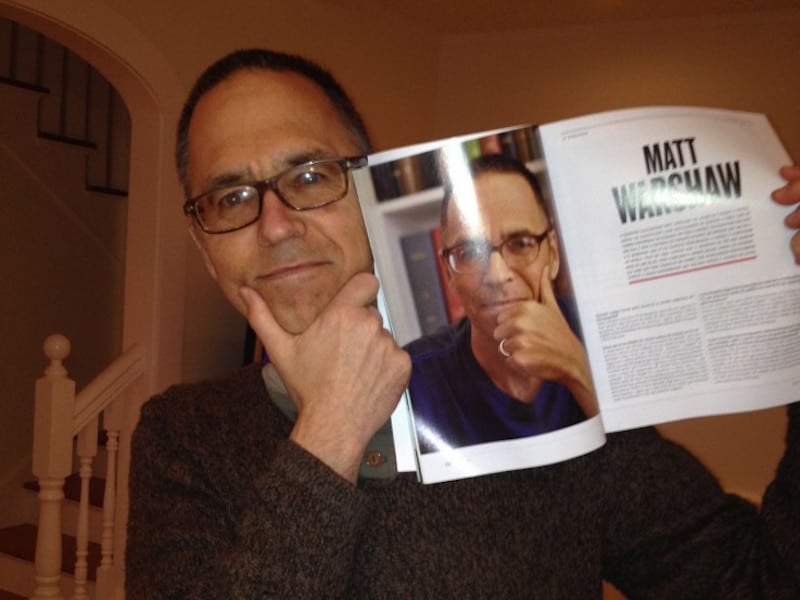

Matt Warshaw is an artist producing in his absolute prime. Come marvel!

I get v v v v v v v v vvvv bored with myself sometimes. With my own addled mind. Look at me. Just poking at this or poking at that. Poking at the dear Cori Shcumacher or Sharkbanz or The Inertia or WSL CEO Paul Speaker….. Don’t I have anything better to do? Better to write? Something real to contribute to this world?

Duuuuuuuust in the wind. All I am is dust in the wind.

So thank God for Matt Warshaw! He graduated with honors from Berkley with a degree in history. Did you know that? Did you know that he doesn’t just pretend to be smart but actually is? And his writing style… I tell you what, when I read Matt Warshaw it is like drinking a delicious cold-pressed green juice. Like eating an organic free range duck l’orange.

His work nourishes the soul and will be around forever and he just added a whole new series. The History of Surfing!

Just read from Chapter 1 as Matt takes us through surfing’s earliest Peruvian roots…

The caballito reed boat was probably invented around 3000 bc, as tiny coastal enclaves of northern Peru coalesced into larger, more complex villages and communities. Traders used the caballito to move goods short distances along the coast, while fisherman used it as a roving nearshore platform. Peru’s coastline is essentially barren, but the chilly eastern edge of the Humbolt Current—a massive nutrient-rich gyre moving counterclockwise through the South Pacific—is more or less a solid wriggling mass of anchovy and sardines. Fishing was, and remains, a Peruvian necessity.

The caballito is organic and decomposes quickly, so there are no examples from even fifty years ago, much less any from antiquity. Used daily, a caballito remains seaworthy for about six weeks, at which point the reeds turn mushy. The outer layers are then replaced, or the entire craft is thrown away. The modern caballito is thought to be built along much the same lines, using the same techniques, as those made thousands of years ago. Fresh-cut totora bunches are spread out to dry for three or four weeks, during which time the reeds stiffen and change color from green to brown-speckled beige. Hundreds of reed pieces are lashed together into component parts, which form the long front-tapered “mother” pieces, two of which are then placed side-by-side and bound together. As the final set of girdling ropes are installed, the prow is given its familiar dagger-like lift, which allows the caballito to navigate through the surf without nosing under. A rectangular storage area for nets, floats, and the catch itself is hollowed out near the back. The paddle is made from a single thick piece of horizontally-cut bamboo. An average caballito is 12 feet long by 2 feet wide and weighs 90 pounds, and it has the same awkward portability of a full-sized canoe. The ancient Egyptian papyrus raft, which predates the caballito by a thousand years, was a surprisingly similar craft, with its multi-bundle reed construction and raised prow.

If today’s caballito closely resembles those of antiquity, the mechanics of its use are likely the same, too. In Huanchaco, a Conquistador-founded town north of Trujillo and Chan Chan, the caballito remains the fisherman’s craft of choice. Along with the rest of Peru’s west-facing coast, the beach at Huanchaco is almost always blanketed in a light salt-tinged haze, the result of the cool Humbolt Current surface water evaporating and condensing as it glides past a warm shoreline. A concrete boardwalk fronts the beach, and local fishermen now paddle out wearing polyester soccer jerseys and surf trunks, but the scene is often shrouded in a kind of grayish prehistoric gloom.

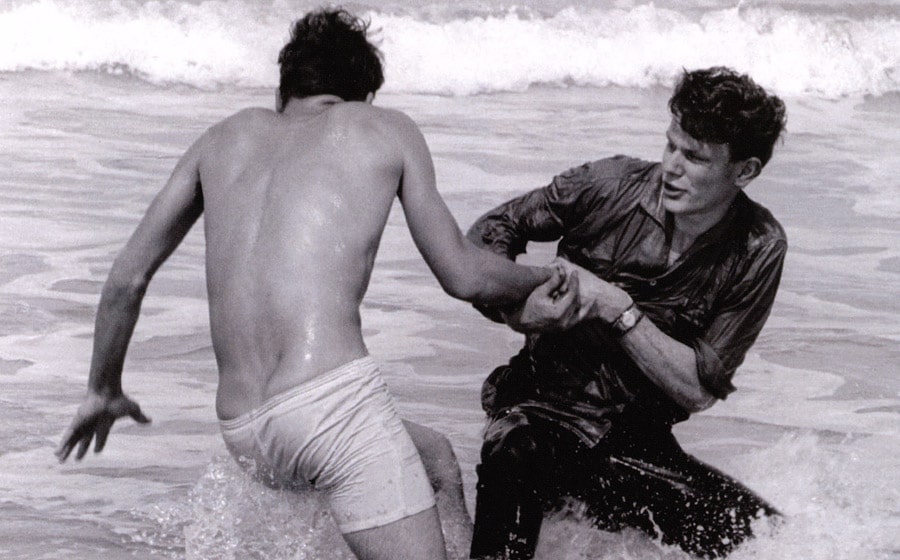

A caballito will flex slightly as its owner heaves it into the crook between head and shoulder and then grunts his way down the beach to water’s edge. Huanchaco has no harbor or breakwater, but the waves at the base of a long point in the middle of town are always smaller and gentler than the beaches to either side. This is where the fishermen put in. Kneeling or straddling the caballito, he grips the bamboo paddle and uses a kayak-style stroke to push through the incoming surf and out to the fishing groups just offshore. On the return trip, some paddle to the beach during lulls. Those who ride waves do so carefully and directly, dipping the paddle into the water to maintain balance as necessary. The flipped-up bow prevents the caballito’s nose from pearling under while being pushed to shore, and the motion is simple, smooth, and unvaried. Wipeouts are rare. Only in recent decades, as the caballito became a beachside attraction, have the Huanchaqueros put a bit of showmanship into the routine, raising the paddle overhead, or trimming at an angle across the wave, and occasionally even standing up.

I mean…. I mean…… “grayish prehistoric gloom?” “…a massive nutrient-rich gyre moving counterclockwise through the South Pacific?” “A caballito will flex slightly as its owner heaves it into the crook between head and shoulder and then grunts his way down the beach to water’s edge?”

It’s art! All of it! Art!

Thank God for Matt Warshaw!

Go here for your own nourished soul.

But wait? You feel like some more Chas Smith? Oh gladly! Just close your eyes. Only for a moment and the moment will be gone real quick. All my dreams will pass before your eyes of curiosity!

(Hint: My dreams usually involve poking at the beloved Cori Shroomactor, poking at Sharkbanz, poking at The Inertia and poking at WSL CEO Paul Speaker. Duuuuuuuuust in the wind!)