USC scientist Adam Fincham and how he breathed life into Slater's outrageous dream.

For the past several, I don’t know, years, I’ve been trying to swing an interview with Adam Fincham, the genius who brought Kelly Slater’s dream of a barreling wave pool into relief.

Fincham is a Research Associate Professor at University of Southern California and has worked with Kelly since 2006 to create a masterpiece of bathymetry on the outskirts of a lousy cotton-farming town four hours north-east of Los Angeles.

Today, in sciencemag.org, and via the keystrokes of staff writer Jon Cohen, we get to examine the Slater-Fincham pool, and the “obsessive compulsive” pair’s relationship, in detail.

Let’s read a little

In 2006, Slater, the world’s most famous surfer, approached Fincham, who took on the challenge of mimicking nature in a tank. “I had no idea who he was,” says Fincham, who grew up in Jamaica and began surfing only when he came to USC. To develop the wave, Slater founded his own eponymously named company, which promptly hired Fincham.

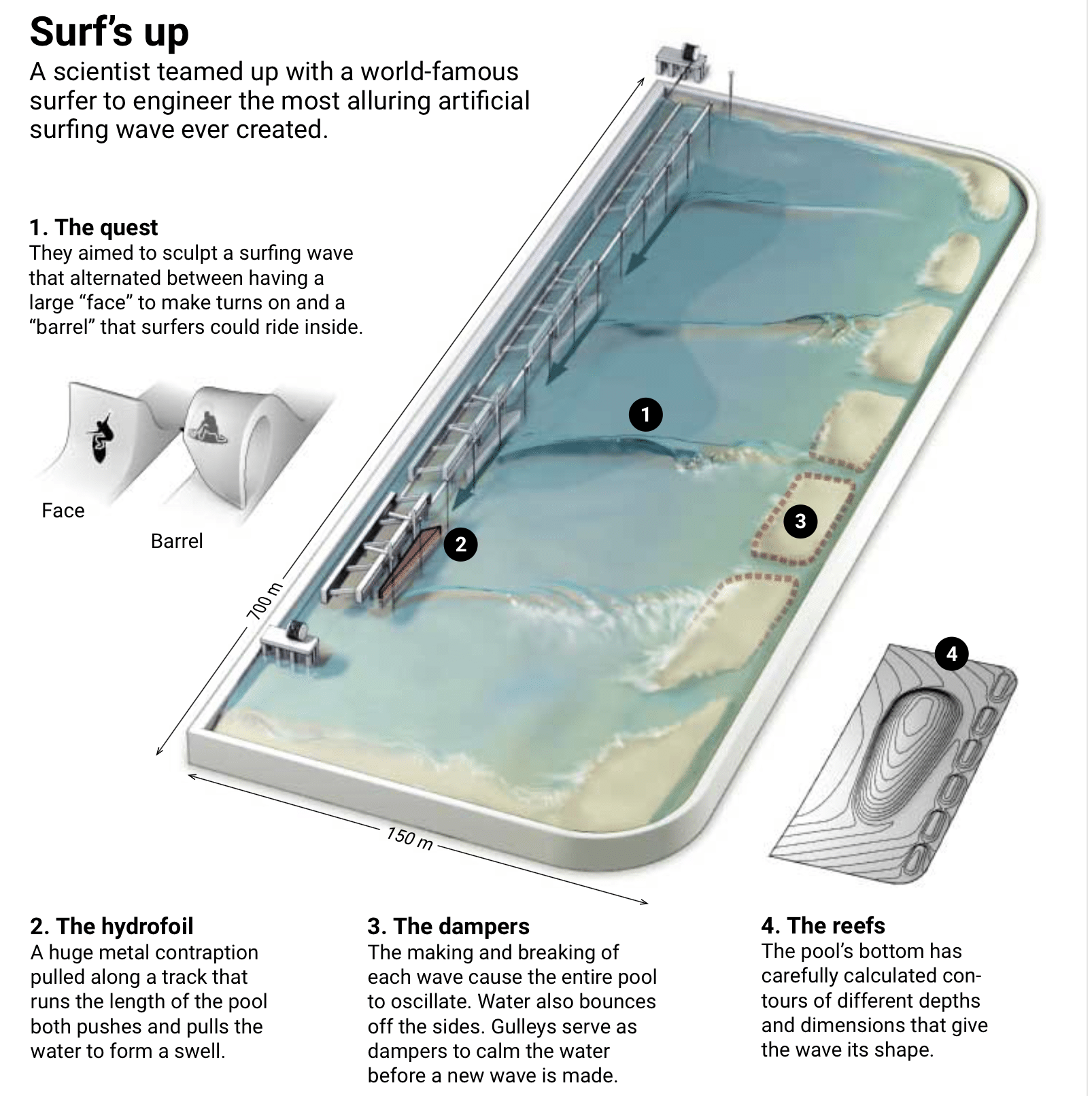

They began in a laboratory wave tank. Whereas many wave pools use paddles, plungers, caissons, or other strategies to effectively throw water into the air, Fincham’s team designed a hydrofoil that is partially submerged in water. As it cuts through the pool, the hydrofoil moves water to the side (but not upward) and then pulls back on the forming wave to “recover” some of the water it pushed away. The result is what physicists call a solitary wave, or soliton, that mimics an individual swell in the open ocean.

Then Slater’s surfing experience came in.

“It was [Fincham’s] job to figure out how to make that swell, and it was my job to figure out how to break that swell,” he says. It takes a shallow “reef” of just the right shape to turn a swell into a surfing wave. To fine-tune the shape of the pool bottom, the team relied on Slater’s input and on massively parallel supercomputers that often had to run for weeks at a time to complete a simulation. In silico, a wave is a mesh of millions of cells that represent air and fluid.

Computations for each of the cells and how they interact with each other simulate the evolving wave as it develops a face and a barrel. The computations are “mathematically horrendous,” says Geoffrey Spedding, a USC fluid mechanics specialist who has collaborated with Fincham but had little input on this project.

Fincham’s team transferred the lab findings to the Surf Ranch, a rectangular pool that was originally an artificial water skiing lake. The hydrofoil—imagine a vertically oriented, curved, stubby airplane wing—sits in water a few meters deep. It’s attached to a contraption that’s the size of a few train cars and, with the help of more than 150 truck tires and cables, runs down a track for the length of the pool at up to 30 kilometers per hour. This creates a soliton that stands more than 2 meters tall. The pool’s bottom, which has the springy feel of a yoga mat, has different slopes in different parts, and the contours determine when and how the soliton breaks. The patents also describe “actuators” in the hydrofoil that make it possible to adjust the size and shape of the wave to suit different skill levels.

The hydrofoil moves up the pool to create a wave that breaks from right to left. Giant gutters serve as dampers to reduce the seiching and limit bounce back from the walls that border the pool, but it takes 3 minutes for the waters to calm. Then the hydrofoil travels back down the pool and forms a wave that breaks in the opposite direction. The ride can last for a ridiculously long 50 seconds, and the wave alternates between big faces to carve on and barreling sections. Onlookers hooted wildly during that September contest when Stephanie Gilmore, who has won the women’s title six times, stayed in the barrel for an astonishing 14 seconds.

And the future?

Slater envisions that wealthy surfers might want to buy into luxury, private resorts built around a wave, similar to the Discovery Land Company’s high-end golf communities around the world.

Like this, sorta.

Not that everyone’s convinced.

Some see a multimillion-dollar novelty project that’s commercially doomed. “The wave is fantastic, epic, everyone would love to surf it for sure,” says Tom Lochtefeld, a San Diego, California, inventor whose company Wave Loch produces the FlowRider, a “sheet” of water ridden on what looks like a snowboard. “But it’s an evolutionary dinosaur.”

Read the rest of the story here.