Read the story The Surfer's Journal rejected!

You’ll recall back in September 2017, the World Surf League put on a professional surfing event at their Kelly Slater Wave Company Surf Ranch property in Lemoore, California. It was called the Future Classic, and it remains to my knowledge the only professional surfing event in history to which the media was specifically un-invited. Actually TOLD: don’t show up.

I had long since ceased to be baffled by the WSL’s often puzzling actions, especially its awesome control-freak secrecy — after all, this is an organisation that after four years in charge of the world tour, was yet to allow its actual owner to be interviewed.

But, man! Having a pro contest in Kelly’s pool and nobody’s allowed to watch? You’re just asking to be kicked in the head by every surf journalist on the planet, and sure enough, that’s pretty much what occurred.

A coupla weeks later, in early October, the shaper Dale Wilson posted on Facebook a shot of a board he’d made me, a classic ex-Allan Byrne six channel swallowtail, 6’0” x 185/8” x 21/4”, just gorgeous.

“This thing’s gonna ride some good waves,” I posted under the photo. Then, still feeling a little bit of acid regarding the Future Classic, I tagged Kelly Slater. “Think of this in Surf Ranch Cylinders,” I urged him.

“Ha ha,” came back KS, never short of a snappy reply, “Too bad you’ve been so critical or you’d find out! Might have to try one and let you know!” Then laughing emojis, etc.

Christ, I thought, OK, it’s like that is it. Quickly tapped, “I’ll lend you one, promise,” and kinda forgot about it.

And this is not a word of a lie — four days later, Dave Prodan, the WSL’s Vice President of Global Identity, contacted me.

“I have the opportunity to bring some folks to the Ranch for a day,” Dave wrote. “No pressure, no expectations. I know it’s short notice.” And named a date three weeks away.

Well, what would you do? Something like I did, I bet — step into a rental car with a board bag and a wetsuit, and take off up I-5 out of Los Angeles, heading toward Lemoore, site of the greatest and most carefully curated mystery in surfing. What the hell was going on up there, really? Could all the rave reviews, the video clips, the 15-second tube rides with their flawless complexions, the mad idea of surfing liberated from the Ocean — could it all exist, in whole or even part? And most of all: what’s it like to ride?

——

Dave told me to keep it confidential. That lasted about five minutes. Swiftly it was confirmed that several of my fellow journalists had also received the Golden Ticket. A deal of wrangling had already commenced, in which they were frantically trading off story rights for air-tickets.

Some were frothing, others wary, if not cynical. “What if it’s a set-up?” muttered my buddy Sean Doherty. “Revenge for us all slagging it off so hard? What if Kelly just wants to wait till we’re in position, then send an eight-foot bomb from nowhere and humiliate us all?”

Me, I was conflicted. Frothing, yeah, of course I was frothing — when it comes to surfing, that’s almost my entire emotional range. There was some resentment too, left over from the way this Pool had been pitched into all our lives, yet simultaneously denied to us: all those clips I was now re-watching in preparation, so neatly edited, so hollow and glistening, and so totally unavailable.

But further down, a part of me was agitated, fearful of a simple yet awful possibility: that the Pool wasn’t just good, but better than good, so good, in fact, that it would outdo any normal surf experience. None of the surfers I’d talked to who’d ridden it seemed to be able to give me a clear take; most seemed slightly baffled, as if they’d seen something outside their surfing imaginations. So the fear persisted. If humans had indeed made a wave that outdid Nature, then might it not be the beginning of the end of History? The very idea of surfing, the sheer joy and freedom that somehow made it through the cultural membrane from Polynesia to the West and survived every indignity we’d managed to throw at it, would just disappear, replaced by a turnstile and a ticket. The final triumph of Western civilization: pay-per-wave.

The rest of me was, like, come on. Cease these 3am thoughts. It’s a surf trip. Treat it like a surf trip.

But man, the circumstances. Nobody takes 1-5 into the central valley on a surf trip. The road winds out of LA, past all those horrendous Simi Valley type places, then into the deserted hills to the northeast, and plunges thence to the valley floor. The land grows flatter, and everything sorta disappears, aside from trucks and fast food establishments. I ignored all the roads heading west toward the coast, took the 41 north-east, got off at the Lemoore exit, and went looking for the pool.

——

The WSL Surf Ranch is on Jackson Road just east of 18th Street, maybe a mile and a half out of Lemoore. It’s easy to locate on a map, but drive past and you wouldn’t pick it. There’s no banners, no tourism signposts (“This Way To Famous Surfer’s Dream Hobby!”). Just a neat wooden fence maybe seven feet high, enclosing the entire property, with one gate halfway along its frontage. The gate was closed, with no visible sign of what lay beyond it. I drove past slowly several times, wondering if I should pull over and jump the fence just for the hell of it, but convinced myself not to. This was private property, for chrissake.

Instead, I turned right on 18th, and drove down to the biggest building in Lemoore.

The Tachi Palace and Casino is the area’s drawcard. I pulled up in the parking lot, climbed out, and was instantly assailed by the horsy reek of dung fertilizer. Like everything else in Lemoore, the Tachi Palace is surrounded by farmland — once-fertile soil exhausted by 140 years of cropping, and kept alive by thick applications of poo. They have to work hard to keep out the flies.

It’s a chill sort of joint, though. No Vegas shtick at the Tachi Palace. A good room is $170. The check-in lady smiled at my accent and told me, “You’re here to surf that Ranch. I heard they were opening it to the public.” I asked an assistant manager if he’d seen a bump in accommodation as a result of the KSWC coming to town. “Oh yes,” he said, “it’s noticeable. Maybe 20% up?”

This was good, I thought. Lemoore needs income. I walked main street that afternoon. It’s full of elegant buildings. This wasn’t any old central valley farm town, once it was well known for its literary society. Today, half the buildings are empty, and most of the people I saw were gathered around an ATM, punching buttons and swearing silently.

I wandered around for a while, pursued by an eerie sense of dislocation. There was a wave somewhere nearby, but there was no ocean. That broad open watery space, where a surfer’s eye naturally comes to rest in the ancient ritual of the surf check, wasn’t available, and farmland wasn’t doing the trick.

Prodan’s instructions included dinner at a Mex restaurant in Lemoore. I can’t recall much about that dinner other than it being unlike any surf trip opening night in my extensive surf trip history. For one thing there were fourteen surf journalists present, mostly looking nervous as shit. For another thing, the WSL paid. As far as I was concerned that was a win right there.

——

I slept restlessly and woke early, though there was little point. There’s no dawn patrol at Lemoore. The instructions were for a 9 am arrival and a 10 am start. I drank every bit of coffee available in the room. Eventually I rode the elevator down to the lobby, where I encountered none other than Sophie Goldschmidt, the WSL’s new CEO. Sophie is British, warm, and during the time we spent in Lemoore, the very epitome of the gracious host. She is tall and walks with a very slight stoop, which somehow adds to her easy charm. “I’ll buy you a coffee!” she said brightly. But much as I wanted to talk with Sophie, I suddenly and very badly now wanted to see the Ranch. I made some mumbled excuse and drove back out to Jackson Road.

This time, the gates swung smoothly open to reveal a small parking lot and a neatly kept building. Inside the building is a spacious changing room, complete with filled board racks, wetsuits, leashes, towels, wax, everything you might want to use during a surf. Everything feels organised, low-key, stylish. A door opens from that room into a hang-out area, then into another room dedicated to the Pool’s design, with bathymetry charts and illustrations of imaginary Pools of the future.

I ignored all that stuff and ran straight to the low slung wall beyond, and gazed out over Kelly’s modern miracle.

Immediately I realized how much of it has been hidden in the videos. The KSWC Pool is contained by a concrete wall, maybe four feet high on its outer rim, running all the way around the pool’s perimeter — maybe 700 yards end to end, and 150 yards wide. On the inner rim, the wall falls away on its open side to a broad trough maybe eight or 10 feet deep, which runs most of the way down that side, before circling around at both ends and joining up with the body of the Pool.

Halfway down this open side of the Pool is a large control tower set-up. From here they run the Pool, watching an array of sensors, picking up any issues with the machinery or waterflow, and eventually, setting it in motion.

On the other side of the Pool is a heavy blade or foil, half-submerged and around 40 feet long, and mounted train-like on a monorail track running the length of the Pool. When dragged along the track, this foil forms an exaggerated version of a ship’s prow-wake, in effect pulling the wave from one end of the Pool to the other. The machinery is separated from the body of the Pool by a steel mesh fence, held up by a series of numbered metal posts, 100 in all, each around four metres from the next. Everything is gray, precise and industrial; it looks for all the world like a high-tech watery prison.

Most of all, there is the captive water, surprisingly less of it than I’d expected, silvered over now in the foggy morning light, and unlike any surf spot you might think of surfing, absolutely dead flat. Not a ripple.

Completely fascinated, I ran the length of the Pool, obsessively scribbling down every sight and sound in my little notebook. I was there with thirteen other journalists, and I was the ONLY ONE with a notebook. Everyone gazed at it as if it were a club-foot. “Ha ha! Look at Nick taking notes!”

Off to the west was another pool, roughly the same in dimensions but much simpler in layout, almost like a dam. A couple of boats floated in it. This still belongs to the original owner of the whole property, a rich out-of-towner who’d bought in so he could have his own private wake-boarding tow park. He’d grown bored, selling Kelly half for several hundred thousand dollars, and buying a nearby golf course instead. Between the two pools, under a large eucalyptus tree, was a little silver Airstream caravan. This, I later found, was Kelly’s hideout. “He came up right after he had that foot surgery from J-Bay,” one of the staff told me. “He just stayed up here for weeks and weeks, tinkering with the computers, totally absorbing himself in it.”

You would, wouldn’t ya, I thought. But not now. There was no sign of the maestro. Evidently, if he was watching, it was via CCTV.

——

For the purposes of the sessions, we’d been split into groups of four, the idea being that everyone would get a couple of waves made for them, then sit in line and wait for their next turn. We were gathered together and lectured about the Pool process by a man whose name I failed to note down. He was not tall, yet exuded an air of authority that instantly set my teeth on edge. “Everyone wears a leash,” he told us, “That’s just how it is. There’s a secondary wave after the wave you’ll ride, a lot of people want to try to mess with this, you might want to, don’t mess with it. Don’t try to do too much on your first ride, just cruise it, there’ll be plenty of time to try stuff later.”

He introduced the lifeguards, three of ‘em. I counted 17 employees at the Pool, not including Dave Prodan and Sophie Goldschmidt, but including Chris Mauro, the ex-Surfer editor who now works for the WSL, and Chloe Kojima, one of the WSL media handlers, who lives in Los Angeles. Chloe and Mauro jumped in with various groups; I got the strong sense that a visit to the Pool is considered a buff job for WSL employees.

Vaughan Blakey was in the first group. Instantly Vaughan volunteered to ride the first wave. Vaughan is the editor of Surfing World in Australia, and if I was the most curious person present, he was the most completely psyched. “I just wanna get a barrel,” he’d told everyone at the dinner the night before. “That’s all I want!”

I ran to a point just past half-way down the Pool, unspeakably eager to see a wave. Somebody shouted “One minute!” through the loudspeakers. This very pregnant minute passed.

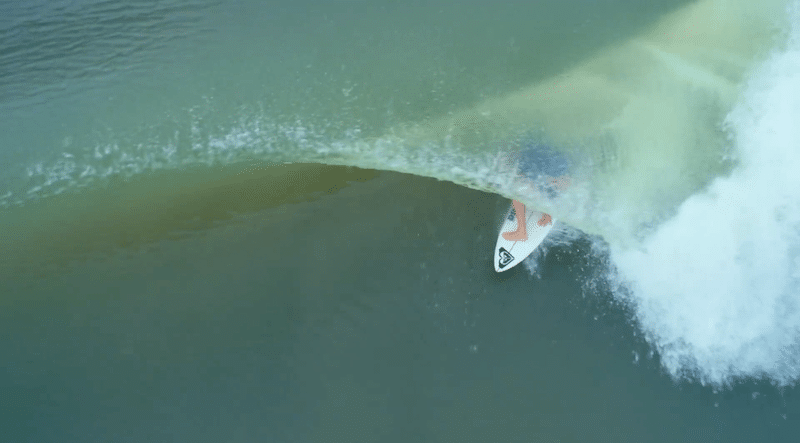

The machine made a clanking noise, then a sort of low-level grinding, and began hauling along its track, and my God, there it was. A wave! Or something like that. It rose from the flats, sloped across the Pool, and approached Vaughan, building as it came. I could hear people squealing with excitement, looked around to see who it was, couldn’t tell, and looked back to see Vaughan gliding along in his barrel. Just like in the video clips.

He came out, looking as stunned as anyone, and headed off down the Pool, while the wave exploded over a raised area of fabric-coated concrete known as the Beach, surged up against the wall, and chucked spray all over my notebook. The spray was still flying — the entire Pool aswirl, in fact — when Vaughan got clipped on the end section.

Immediately I abandoned my post and raced back to the board room, where I’d left my quiver, such as it was: the 6’0” six-channel, of course, plus a board I ride often in regulation Sydney surf, a 5’ 91/2” Maurice Cole “moontail” swallow, super deep concave, slight vee behind the back fin, hard rail throughout. Very light. It works at Lowers. I figured it’d work here.

I racked the six-channel, took the Maurice, and trying not to rush, stepped past the concrete wall into the Pool.

On contact, the water was cool, murky, fresh, and when stirred by movement, emitted an occasional whiff of chlorine. I walked carefully across the Beach, and paddled maybe 20 yards, across to a metal pole labeled “31”, where I’d been instructed to wait for the wave.

“One minute!” said the voice through the loudspeaker. Thus commenced possibly the strangest minute of my surfing life. I sat there, breathing softly, clearing my mind, the way I’d learned to do in competition.

It felt almost exactly like being in a professional surf contest.

The machine clanked, slid forward. The wave emerged from behind the fence, first as a triangle of lifted water, then as a wall stretching across the whole Pool. Calm, yet slightly dubious, I turned, paddled into it, and stood up.

——

Instantly I was a surfer again. Until this moment, everything had seemed strange and dislocated; now as I felt the pressure of water on board and the movement of the wave, it all became familiar. I pushed a little on the inside edge of the concave and the board responded exactly as it had on hundreds of other occasions. I turned lightly up and down the face and let my focus broaden to absorb the wave. Its energy felt quite direct and clean, like a long-traveled groundswell, yet also softer than I’d expected — while the wave’s angle to the bottom contour caused it to feel as if I was moving quickly, the wavespeed felt a little out of sync with the underlying surge.

The foam line receded across the pool and away from the fence-line, and I slowed a little to follow it. With no warning, the wave base fell away, and everything steepened into a short curve. Ooooo, a barrel! I raced it for a moment and turned into a stall mid-face, until I was half-in and half-out of the tube, and just let it run out naturally. Again there was a slight sense of the wave behaving above itself, so to speak — most hollowed-out pointbreak style waves have a lot more grunt behind them. (Later I figured out this was due to a fundamental difference between the Pool wave and a wind-formed ocean wave; an ocean wave pushes on to a sandbar or reef, drawing water into itself as it moves, while the pool wave is pulled on to its bottom contour, dragging behind the foil, like an obedient dog on a leash. All the water displacement occurs behind it.)

The barrel receded and I was over near the fence again, with a lot of half-steepened face between me and the foil. It felt as if turns up and down the face were called for — “carvedowns”, in the immortal lingo of Joe Turpel — and so I chose to do a few of these. It was outrageously easy. I realized with a little spark of surprise that the presence of the foil and the fence wasn’t distracting me in the slightest. Ian Cairns had told me it was like surfing northside Huntington rip bowls, with the pier in your face, and he was almost exactly on the money.

The ski, on the other hand, felt like a worry. Raimana was driving it along the inside edge of the foam line, just ahead of the wave, and yelling encouragement: “Go brother go go go! Here it comes! Chase it! Go! Barrel!” I had a line in mind I wanted to draw, something I’d seen Kelly do on one of those flawless videos: a sort of fade at speed down to the corner under the foam, then an extended turn to mid-face, preserving speed for the long end section tube. But the ski felt too close for comfort, so I just cruised a couple of turns and held the speed into the final tube section. The foil slowed, then stopped, and the wave lost all energy and vanished.

——

I sat there fizzing with post-wave adrenalin. The Pool! First ride! Immediately I wanted another. I paddled back and forth, trying to settle myself by imitating my normal lineup behavior, watching and feeling the reverberations as the Pool settled itself by other means. This never entirely happened: even as the control tower barked “One minute!” again, I could still see a slight movement of water end-to-end, causing the water level to rise and fall several inches along its length, in intervals of around 30 seconds.

Now for the left. This time Raimana instructed me to sit near the pole marked “71”, and do exactly as I’d done on the right — relax, let the wave come to you, paddle down not across.This all happened as easily as it had on the right. The bathymetry of the Pool is exactly symmetrical, so in theory the left should precisely match the right, but the sensations in the ride were different. I could almost feel a draw from the base of the middle section, even though it didn’t feel as hollow as the same section in reverse. It let me spin the tail off the top and do a little free-fall thing down the face. The variation was small yet distinct.

I’m sure this was the result of that minor water movement I’d seen while waiting. Instead of detracting from the ride, it caused me to switch on and pay more attention; if each wave was different, this Pool was more interesting than it seemed. It was also a little comforting to know that even here, where it was trapped, water was running the show.

Riding backside, I could see the ski a little easier, and thus felt less bothered by its presence, so drew a slightly better line into the end section and got a nice little backside barrel. The wave died just as it had at the other end. I came up to see the lifeguards grinning at me, and I realized I was grinning back.

——

I didn’t get another wave for some time. Instead, Raimana shuttled me off to the other end of the Pool, and I watched the rest of my group. They were riddled with nerves. Jeff Berg, a highly competent surfer, failed to catch his left, and felt awful about it. “I wankered it, Nick!” he groaned.

I wasn’t surprised at the nerves. The Pool exposes your every habit, and I am not talking about technique. What is it you usually do during a surf? Do you even consciously know? (I bet you don’t.) Do you paddle out and catch a lot of waves in the first 25 minutes, then sit and grow more selective as time passes? Do you ease into it over an hour? Whatever you do, it will be examined in the Pool. You will be confronted with your entire surfing oeuvre, and there will be no way around it, not if you want to ride a wave.

This stuff is old news to a CT pro, who knows his or her surfing rhythm inside out and who adapts almost instantly to any new surfing environment. Yet even they have admitted to nervousness in the face of the pool — this spot that prior to riding, they’d seen only as everyone else has, via curated video clips that give you almost no idea of its reality.

Between sessions I wandered down the perimeter again and again, trying to fully absorb the place. I’d never expected to see so much human ingenuity, time, and money expended on such a thing in my lifetime. I felt as if I were on another planet.

I stood beneath the control tower, but foolishly didn’t go up to watch the three tech guys at work. Instead I asked Noah Grimmett, who has been overseeing the project for the past 12 years: do they just press a red button or something? “Yes,” he said. “In a way. But there’s a lot more going on than that.” A range of sensors are mounted on the inside of the pool, providing feedback on water movement, temperatures, and much else. The KSWC team had brought in experts from Universal Studios and other tech-heavy amusement parks — people who work on reliability, safety, and all the systems that underpin the hotshot rides in big theme parks. “The construction is one thing, that’s got to be done right, of course,” he said. “But it starts with the engineers.”

Noah told me more about their future plans. The “commercial” version of the Pool will hide the machinery — the foil and monorail — and have viewing stands mounted above it, so people can look down into the wave as it advanced along the pool, a bit like the view from a pier. I asked him about a photo I’d seen in the clubhouse, a pastiche image showing a Pool to come, with a realistic-looking Beach, submerged rocks in the lineup, and small hotels and restaurants scattered casually about amid tropical scenery. “Something like that,” he said. “This is a skunkworks. We’re just at the beginning here.”

I spent some time talking with Sophie Goldschmidt, the person tasked with selling the Pool. In early 2017 the WSL took a majority share of the KSWC; part of the WSL CEO job description specifically spelled out this task, pricing Pool franchises at $25 million a pop. Sophie seemed to bear this pretty lightly. I asked her if she was already growing a bit bored with watching people surf. “No!” she said. “Not at all. It’s such an unusual sport. All the other sports I’ve worked in, if the athletes were on a break, the last thing they’d do is play that sport. But as soon as the pros get time off, all they want to do is plan surf trips. I can’t tell you how rare that is.”

Sophie was inveigled into surfing by her longtime boyfriend, an Australian who is a keen surfer. They went on holiday to Bali 13 years ago, and she did a surf lesson. She is an ex-pro tennis player, and thus understands technique development, but as the rest of us have discovered, water is something else again. “I’m pretty good at most sports,” she said. “But surfing! I couldn’t do it. I could not do it. At the same time, I’d never had so much fun just trying to do something.”

She hadn’t planned on this job at all. “I’d already accepted another job (in the UK), I’d started the process of buying a new house in London.” She says she was converted after meeting the Ziff family; like everyone I’ve spoke to who has met the Ziffs, she found them delightful, intelligent, and committed enough to pro surfing to convince her.

But what a job! Sophie sketched a quick verbal outline of the WSL’s plans for the Pool, which she calls a “wave system”. They hope to have six or seven Pools up and running around the world in the near future, with Championship Tour competition built in. “Then there’s the Olympic Games coming up … I really think surfing is about to have a moment!” she said, exuding a kind of native enthusiasm.

She paused, looking off into the middle distance, as if sensing for a moment how crazily optimistic this all sounded. Then she smiled, switching on the charm again. “Of course it might all fall apart — but we can’t just sit still.”

I sent Kelly a couple of texts, letting him know our progress through his astonishing creation; at some point he replied with an emoji: thumbs-up.

——

As the day went on, the sense of novelty began to fade, and I grew more impatient. It began to dawn on me that the wave itself held little challenge; instead the challenge of the Pool lay in increments of performance, advancing in small steps, the kind of stuff an elite pro surfer deals with on a daily basis. The way a pro typically takes on this challenge is via relentless, omnivorous wave-catching, repeating moves, often over hundreds of waves a day. But in the Pool, at least the way we were playing it, the wave count was severely limited. You got a right, and a left, then you hung out for 30 minutes, hoping your buddies fucked up so you could steal their waves.

I liked this, by the way, even though it cost me. It seemed to humanize the thing. Late in the day, I was waiting halfway up the Pool, two back in line, when Vaughan Blakey fell in with me. I’m not exactly sure how this happened. I think Vaughan had just poached someone else’s wave. In any case, we both watched as Todd Prodanovich from Surfer magazine took position on the left.

We looked at each other. We both knew Todd was likely to bog this wave. Todd was riding a very elegant twin-fin, and doing so with style, but it was a twin-fin, and he was backside on the left.

“I know it’s all yours, I won’t try anything,” swore Blakey, and paddled up the Pool, taking a position upstream from me as Todd paddled into the left.

Todd took off, did a couple of set-up turns, came into the opening stanza of the wave, and sure enough, the twin-fin said No thanks.

Ha! I thought. This is my Pool swan-song. I am going to smash this thing.

But even as I contemplated this smashing, Vaughan turned, and began paddling into the wave. Unable to stop himself, he leapt to his feet and pulled into the section as I hung in horror on the shoulder.

He fell off just as the wave passed the point at which I could have caught it.

I should have been furious, but what the hell? After all, in Blakey’s shoes, I’d have done exactly the same thing.

As the sun fell away, we hung out in the Jacuzzi, drinking beer and an excellent chardonnay. Group pics were taken, and thanks were given. In the midst of this, the tech guys descended from the tower, slim men with horn-rimmed glasses and computer satchels. They walked past us, but deigned not to engage; indeed they exuded a faint air of contempt. I tried to see us through their eyes: just a bunch of strangers, tourists really, playing ignorantly around in their machine, while they did the serious secret work behind the play.

——

I never rode the six-channel in the Pool. It didn’t seem necessary. Instead I said my farewells and headed off on the 41, thinking about the day, and feeling a faint sense of relief. Surfing is above all an experience, and experience is how we understand a thing. Having had that experience, I can tell you the Pool is nothing to fear. It’s a completely artificial surf spot, controlled entirely by people in every aspect. There’s no paddling, no duck-diving, no hunting, no positioning, no wave selection, no tidal change through a day, no competition for the wave, no rips, no closeouts, no sense of Nature stepping in to stoke you or fuck you up.

And therefore, if we are to be completely honest, there is also no surfing. You ride waves, but that’s it.

And ultimately, this is dissatisfying. The WSL Surf Ranch is an ideal venue for major pro surfing competition. It’s an epic showcase for pros, and a theme park for good surfers. It’s almost impossibly original, and fun as hell. I’m flabbergasted by what Kelly has done up there at Lemoore; at some moments I think maybe it outdoes all his world championships. After all, people won world titles before him, and they continue to do so since; none, however have built anything like this.

But as a surf experience, it just doesn’t hit the spot. Three days after I’d driven back down the 5, a small late-season south swell arrived in Californian waters, and I jogged down to Lower Trestles for the early session. It was late fall, and the smell of sage was in the air. Small crustaceans scratched around in the wet sand along the shoreline. I could tell Lowers had had an active summer by that sand line, which changes year to year; I’ve been watching it since 1991. A dozen or so surfers were out, most of whom I knew. We told each other stupid jokes, and caught waves when we felt like it.