Understanding surfing through a postcolonial and de-colonial lens.

With the 2022 WSL season now behind us, it is an opportune time to revisit an emergent theme on this august site: that of understanding surfing through a postcolonial and de-colonial lens.

DR and Chas have created space for our collective to educate ourselves on this needed vocabulary and analytical frame.

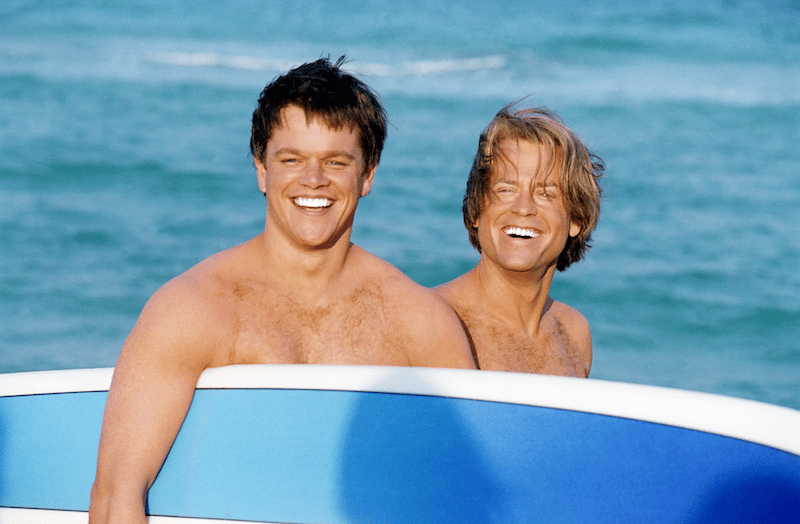

Given the edification I received therein, I want to apply a critical theory lens, informed by decolonial and postcolonial thinking, to the 1987 surf camp classic, North Shore. This movie captured a gestalt within modern surfing and deserves to be excavated, to see how colonial tropes (and heteropatriarchal ones, but that’s another article that someone else can give us) are deeply embedded at the very core of surf culture.

We begin with the setting: an overachieving, eager to please young white man, from a broken home.

This is a statement on emerging family dynamics in white middle class America from the 1980s, as divorce was still stigmatized, and the Spicoli surfer stereotype in full effect. Rick Kane breaks the stoner stereotype with his work ethic and “wear your heart on your shoulder” approach to being an upstanding member of the community, where these character traits grant sympathies for his coming from a broken home.

This background allows Rick Kane to stand in for US entrepreneurial spirit and the naturalness of exporting this benign (on the surface) spirit to the rest of the world, via his impending trip to Hawaii to surf the North Shore.

Kane arrives on the North Shore, naive to local customs, immediately accosted by the savage temptress and seductress in a house of ill repute. Kane’s coded bourgeoisie puritanism makes the correct play and holds out against such seduction, thus arming our colonial protagonist with the moral uprightness needed to justify the exploits to follow.

Kane catches a ride with fellow colonizers, Occy and Alex Rodgers, who goad Kane into stealing sugar cane en route to the North Shore. This stands in for a classist metaphor that belies a central dynamic of colonial expansion: that of the educated, materially abundant and resource rich post-agricultural white empire, belittling and then taking the resource base of the agricultural-based dominated non-white other.

Kane continues his colonial trajectory where his whiteness appeals to the exotic Hawaiian princess, Kiani. Kiani acts out her own Oedipal desires on the groomed white body of Kane, fantasizing of rubbing his back with aloe, as she has done to her own family and fellow subaltern community members. The horse upon which Kiani rides is also a metaphor of her desire to advance her own mobility and social standing, benefitting from white capital (the owner of the horse) to escape the limitations of her own backward, uncivilized upbringing.

Kane, now bereft of his property and with no money, meets Turtle, the classic white-who-has-gone native.

Notice, though, that a turtle is a mammal with the strongest heart. Here Turtle’s nomenclature is a subversive statement that white privilege is long lived, solid, patient, stable, and able to conquer in any environment.

This is echoed when Kane meets Chandler, the latter who has achieved the colonizer’s dream: a native wife, a house on the beach, and credibility with the locals, all who defer to him in the lineup and want to buy the products of his labor. Chandler evidences total appropriation of native Hawaiian knowledge, using folk expertise and colonized traditional ecological knowledge to groom Kane in following in his footsteps to continue the colonization of the North Shore breaks via a variety of superior technologies crafted by Chandler through his industrious work ethic and his copious colonized knowledge of the various surf breaks therein.

Note there is even tension with the alpha-male, Burkhart, the uber-capitalist playing out escapist fantasies on the same colonized landscapes. Chandler opines his products are only made “the right way,” yet Chandler and Kane work together to create a logo that further will allow for the appropriation and subjugation of colonized surf knowledge and crafts, while the veneer of “authentic” stoke allays any capitalist-colonialist guilt, making Burkhart the fall guy.

This move presages the onset of greenwashing within the surf industry as a whole.

Note, too, the etymology of the word “chandler”: Middle English (denoting a candle maker or candle seller): from Old French chandelier, from chandelle. Here Chandler is lighting the way for the appropriate way to colonize the North Shore–it is not via brawn and muscles, a la Burkhart, as that is not a long-term solution to colonization. Rather, it is through charisma and ingratiating oneself into the local populace that colonization is most effective.

This dynamic is on full display as Kane battles Da Hui and the titular leader of this group, Vince Moaloka.

The character arc of Vince is Edward Said’s archetypal “Orientalist gaze” in a nutshell: the dark, exotic other, full of violence and danger, steadily pacified by the grit, superior work ethic, and rational, secularized, democratic knowledge of the West, as embodied here archetypally by Kane.

We see this, too, in the reverse arc of Rocky, the uneducated local thief and thug, who stole Kane’s property. Kane, local beauty in hand, encounters Vince and Rocky amongst the sacred fields of Hawai’i. Here Kiani had already begun the process of freely giving native secrets to the white colonizer, with her body and heart to soon follow; Kane notices his belt buckle on Rocky and challenges Rocky to get it back.

Rocky recognizes the superior military might of the West and tries to create solidarity amongst his brethren, only to be denied by the father figure and leader, Vince. The colonial project is now almost complete, and the pole is part of the metropole.

Only one last transaction is needed: the full taking of the resources from the latter, to fully benefit the former. This occurs symbolically in two ways: the first is Kane taking back his belt buckle. Note here the silver clasp is a metaphor for minerals, which were subsumed by colonial powers on the back of enslaved labor–such is the unavoidable fate of Hawai’i.

The other resource, of course, are the waves–and here again, Kane becomes the conqueror.

But unlike the transparent aggressive colonialism of Burkhart, it is by appropriating Hawaiian soul, as taught by his colonial mentor, Chandler, that allows Kane to emerge as the white victor, overseeing a now conquered empire.

Lest we be remiss and think fiction does not influence lived reality, let us remember that Makua Rothman is the child of Chandler. Here the hybrid figure of Makua, as an innocent real-life child born of a white father who helped form Da Hui, cannot be lost on viewers of surf culture.

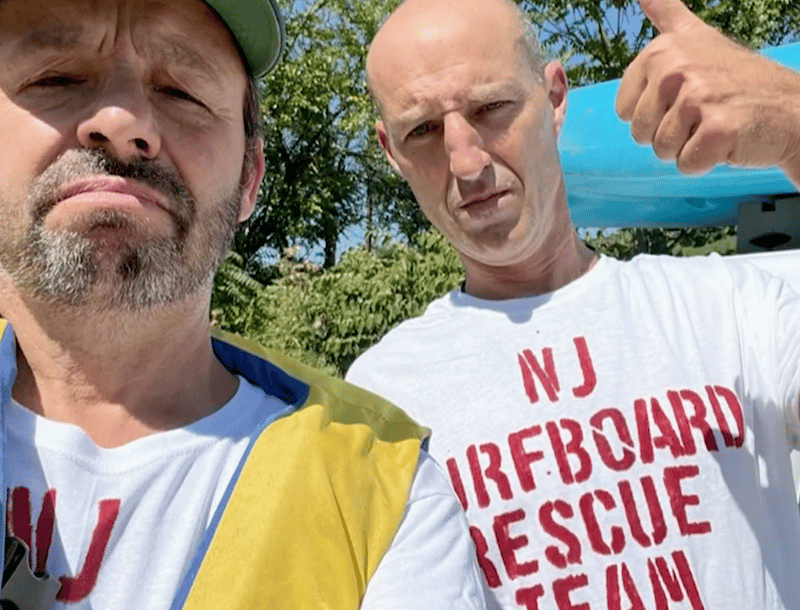

There is a direct line from that scene to Nathan Florence and Koa Rothman sitting at a table at Turtle Bay, discussing their new podcast in 2022, further cementing the colonization of the North Shore by white descended peoples. \

To add insult to colonized injury, Koa is drinking a Coors Light–Coors is of course the business run at one point by Peter Coors, a well known supporter of far-right, conservative politics, which of course target critical theory and decolonial approaches to understanding structural and racialized inequalities.

So where does this leave us?

I must confess, it brings me no joy to undertake this analysis of such a pivotal movie in surf culture; a movie that many have enjoyed from its release in 1987 through today, myself included.

Sadly, I think it leaves us with one major question that the industry must answer, to atone for its laggardness on this front:

When the fuck are we finally getting the god damn sequel?!?!