"As fucked as I felt, it was a highly unusual experience and I’m still processing it.”

Almost two weeks since ultra-endurance athlete Blake Johnston emerged from the Pacific after surfing for forty hours straight and catching 707 waves at an astonishing rate of one every four minutes, a vein in his forearm is attached to an IV, our hero receiving a replenishing dose of vitamin C and magnesium.

Been surfing much? I ask the holder of the world record for the longest surf by way of a joke, to which Johnston, missing the epic gag, details his four am start, the surf school and a wild foil run to wrap up the morning.

Just cause he busted the old longest-surf record and raised $440,000 for practical mental health measures (“I don’t want to just start another ‘conversation’” he says) don’t mean he’s in the bean bag binge watching Love Island like his interlocutor.

He tells me he’s still sore through the shoulders, a deep pain in his upper back and across the coat hanger but isn’t too worried about it yet.

“If it’s still there in around in three months when the adrenalin wears off…well…”

Permanent physical damage is a fact of life for the ultra-endurance athlete.

The night before he paddled out for the world record attempt, Johnston got a text from the man whose record he was gonna smash, South African Josh Elsin, who surfed for thirty hours, eleven minutes, with 455 waves eaten up in 2015.

“He said he felt responsible if anything were to happen to me. He’s a good dude, a legend. He told me goggles are the deal breaker. I told him, you didn’t wear ‘em in the videos and he said he didn’t want to look like a mad kook with his goggles on.”

Elsin told him he didn’t look after himself for three weeks after the feat and, eight years on, he’s still got injuries from it.

“Think about runners on two-day runs,” says Johnston, “some people mess ‘emselves up running out of alignment for a long time, that bad form that comes when you’re tired. Same with paddling, same shit, for the upper body.”

The hardest part of his marathon, says Johnston, who is forty, were the first six hours. The surf was a powerful east groundswell, with rips running hither and yon, and before first light it was calculated he’d duck-dived three hundred and fifty waves.

“I got washed across the whole of North Cronulla, I’m four hours in and I’m weathered, my eyes are stinging and there were hundreds of these big brown jellyfish in the night. They’re dredging in the Hacking (Port Hacking estuary) and that’s where they live. It was kinda comical, man. Five foot straight closeouts in the pitch black. It was so much further out than the lights we had. I had mates come out for water support as part of the insurance and safety procedures. Mates coming out for an hour getting washed around, pinballed, rips going from side to side in the channel. And I was still managing to catch twenty-five waves an hour. When the sun came out on the first day I didn’t expect my eyes to be that sore already, all the salt.”

Johnston’s pal Graham Matheson, an emergency physician who holds a PHD in skin rejuvenation, told him that hydration of the face, tongue and mouth was everything.

“I had a 3/2 Rip Curl steamer on a thirty-five degree day, I was catching, then, a wave every three minutes and fourteen seconds. I wasn’t sitting still and there was a lot of fucking sweat under the wetsuit. Obviously, hydration was massive.”

Apart from the obvious physical horrors, the suffering put Johnston in a place that felt godly.

“I have never experienced the state I was in. It was like I’d lived through it before. As bad as I felt, as shit as my eyes felt, if I breathed through my nose and closed my eyes, I knew that when I opened ‘em a south swell would come because I’d lived it already. I trusted everything about it. As fucked as I felt, it was a highly unusual experience and I’m still processing it.”

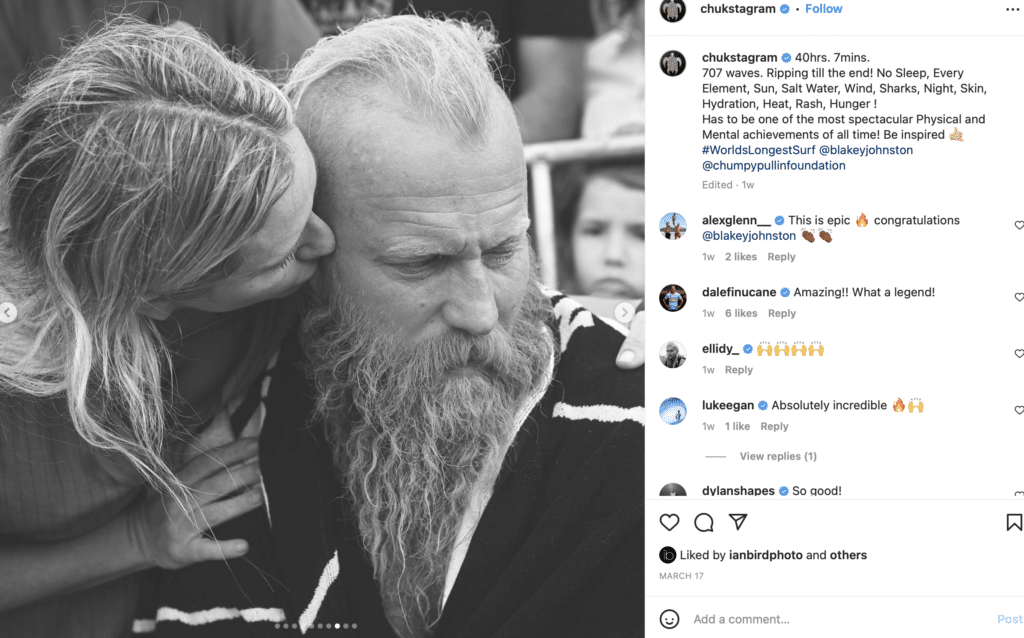

Eleven hours in at around midday, Johnston’s pal the award-winning sports photographer Grant “Chucky” Trouville, padded out along with the local rugby league club, the Cronulla Sharks.

And, in the clear green water, the pair watched as a large turtle swum past.

“You see fuck-all in Cronulla,” says Johnston, “and Chucky said, oh my god, that’s my fucking old boy, his dad who passed away five years ago. His ashes were put in a dissolving turtle shell and paddled out the back of the Alley. He was a big part of the local surf club and when he died he wanted to be put in the ocean and, then, five years later, his son paddles out at the same spot and the first thing he sees is a turtle. There was so much energy around this world record.”

When Johnston finally wrapped his marathon session up after almost two days he was whisked away to the hospital where, he says, “I was pretty hysterical. I was emotional. I wanted to say thank you to everyone and I couldn’t. I was yelling, ‘Why the fuck am I not there? I want to shake their hands!”

An important part of the feat, at least to Johnston, probs not so much to anyone else, was how authentic he made it. He had four Rip Curl jetties and five Chilli surfboards but, to keep it real, wore one suit, rode one board.

“I wanted to do it properly, be vulnerable in front of everyone. I could have made it easier. I didn’t want to pull my wettie down in the water and go to the toilet so I’d run into the toilet, did that three or four times. I dug deeper than I needed to.”

The four-hundred plus gees he’s raised for the the Chumpy Pullin Foundation (Alex “Chumpy” Pullin was an Australian snowboarder and Olympian who died while spearfishing in 2020, aged thirty-two) is, in Johnston’s words, “being used for action. To get kids off their fucking phones, to challenge ‘emselves with ice baths and whatever, to help become more self-aware. I’m not spiritual but these are the practical tools we all have access to. We need to be able to handle life’s adversities. Let’s see what we can implement in our daily lives, let’s see if the power of gratitude can become part of their routines, help ‘em become emotionally more in control and resilient.”

Johnston knows about suicide. His daddy Wayne took his own life and when he was a kid riding for Quiksilver one of that company’s most popular employees, Andrew Murphy, died at the hands of the black dog.

“I think we’re always treading a fine line between feeling good and feeling unworthy of anything. I was an emotional kid. I care a lot about other people and to have that self-awareness helped me a lot through the dark points where I could say to myself, this is unhealthy, this isn’t good.

“(Depression and suicide), those things are hereditary. My brothers have had their moments, haven’t fell great and worked through it. There’s not one solution to it, and it’s ongoing. It’s a constant wave of emotions we deal with through our whole lives.

“So many message came through from people, really positive ones, like you helped me open up a conversation with my kid, fucking heart warmers every day. My eight year old laid on me and asked, ‘Daddy, what is mental health?’ I was nearly in tears, mate. It’s about your being proud of yourself and feeling worthy to your family and friends around you.

“Other people sent darker messages, people who were in similar situations to my Dad asking, ‘Can you help me?’ I’m a surf coach not a psychologist. I do what I can but it takes a toll on you, too. I wrote back to every single person. My wife was getting angry at me!”

How many messages?

“Thousands.”

Keep donating here.