An interview with The New Yorker staffer on a life so beautifully squandered…

It’s hard to step outside these days without tripping over a review of the William Finnegan book Barbarian Days.

The Wall Street Journal called it “gorgeously written and intensely felt… dare I say that we all need Mr Finnegan… as a role model for a life, thrillingly, lived.”

The LA Times said, “It’s also about a writer’s life and, even more generally, a quester’s life, more carefully observed and precisely rendered than any I’ve read in a long time.”

It threw me under the bus of a two-day obsessive read. I’d dived into Finnegan’s work in the New Yorker before, including an excerpt from the book about his time as a kid in Hawaii (read here) and figured the memoir would be gently entertaining but not especially adventurous. I imagined a writer with a loosely knotted bow-tie and a drooping moustache. A delicate New York gentleman, a flabby enthusiast.

I’d only penetrated three chapters into the book when we suddenly camping on Maui waiting for Honolua Bay to break and, shortly after, camping on the empty beach at Tavarua for a week and surfing a new discovery called Restaurants.

Soon, Grajagan in 1979, Africa and, later, among the big-wave surfers of Ocean Beach, San Francisco, and, then, spending long vacations on Madeira, waiting for Jardim Do Mar’s heavy deep-water right to break.

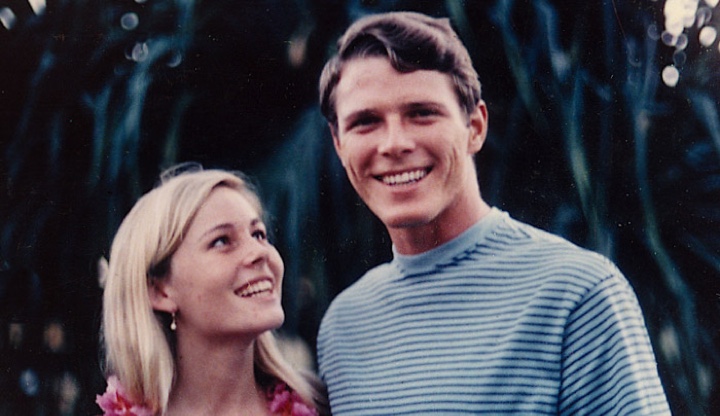

Photos scattered through the pages showed the author to have visible obliques, was long-haired and tanned. Finnegan was, is, a… stud?

As it turned out, the sixty two year old Finnegan is a pal of the former Surfer editor, pro surfer and Encyclopedia of Surfing curator Matt Warshaw. Matt said he’d cast an email introduction, which he did, and then added,

“You know he plays tennis with Martin Amis.”

(Amis, if you’re late to the reading game, is a very famous British novelist. Try London Fields for an intro to his work.)

Finnegan, Warshaw was implying, is significant.

Yeah, he is.

I’d clamour children underfoot for a chance to hear his eloquence in person. I wanted to be blinded by the glare of his intellect, his adventurous spirit, despite my usual rule of avoiding better men. Where I chase the assurance of perfect safety, Finnegan wasn’t afraid to flaunt his follies in the face of danger.

Maybe I could learn something?

Tell me, I wrote to Finnegan, what is the mind-set that consistently sends a man over the ledge?

“For me, it’s usually a much more conscious decision when I don’t go,” he wrote. “That’s when I actually do some thinking, and doubt creeps in, and discretion becomes the better part of valor. This goes for paddling out on a scary day as well as stroking into a scary wave.

“Once I’m scared, I usually stop surfing, or certainly stop surfing as well as I do when not scared. That tipping point has rational content, usually, based on your experience, which in my case is a lot of years now. But it also has irrational parts, which I try to control and tamp down with little pep talks to myself. Unfortunately, I’ve sometimes succeeded in calming myself down to the point that I’ve tried to surf waves I truly didn’t have the board for, or simply couldn’t handle, and had no business attempting, and have then come close to drowning.

“The decision to paddle out on a bigger day is, for me, sometimes a quite separate thing. Often, you can’t actually see from shore what it’s doing. If there seems to be a reliable channel, I’ll sometimes paddle out with the decision about whether to actually surf still reserved. I’m just going out to see what it looks like. I did that a couple of years ago at Tres Palmas, Puerto Rico, on a big swell. I’d never surfed the place before, and we could just catch glimpses of a couple of guys towing way outside, but we couldn’t really see what the waves were doing – we could only see the tops. But I had a gun, so I paddled out.

“It turned out to be incredibly good, and not that hairy – one guy was even ripping on a shortboard. Nobody could see any of our rides from shore. But for me that decision to paddle out usually turns on my own weird fear–a visceral, anticipatory fear of the feeling I get after I don’t paddle out. That sickening, I-didn’t-even-try feeling. It’s the worst. Actually worse, in my experience, than the traumatized, jesus-I-nearly-drowned feeling. Of course, there have been many times I didn’t paddle out and I was sure I made the right decision. Big Pipe, Maverick’s, Waimea, huge Ocean Beach, maxed-out Jardim, etc. Those decisions don’t haunt me. It’s the judgment calls where afterward I think I chickened out that kill me.”

If he could swing back decades, back into surfing prime, in those days when he was all over Tavarua and Grajagan, would he do anything different?

“I would paddle a few hundred yards down the reef at Grajagan and surf the right fucking spots instead of wasting a glorious, super-clean, week-long swell riding big mushburgers up at what later got named Kong’s. That was 1979, and there was nobody around, and my friends and I had never been there before. We were camping in a half-collapsed tree house, and there were only two of us surfing. The place was already famous, and we had heard about these long fast barreling lefts. But we somehow never figured out that the great waves – Money Trees, Speed Reef, I think they’re called – were way down inside someplace. That was the single stupidest thing I’ve done surfing. Otherwise – there are definitely waves I should have gone on, barrels I should have pulled into. But most of the times that I didn’t push hard enough were probably for the best. I got myself into enough trouble. I’m grateful that things didn’t turn out worse.”

Not that he isn’t adverse to a little dance with fate, even in his harvest years.

“At 62, I’m still looking for the same old kicks, I think. Of course, I don’t surf as well as I once did, which is horrible. And there are places, starting with Puerto Escondido, that I know I shouldn’t go back to. I can’t say I’m not tempted, though, especially when it’s flat around here in July. Two winters ago, I got two intense barrels back-to-back on the North Shore. That was just a few weeks after my 60th birthday. No fool like an old fool!”

When I asked if he thought surfing was elevating or just another pointless pursuit he wrote, “It’s supremely useless, I think, and not at all ennobling. Which is not to say that a great many people, starting with you and me, don’t get a great deal out of it – even a reason to live. It just does nothing, obviously, for anybody else. It’s the ultimate selfish pursuit. You could argue that it teaches its devotees a few things about self-reliance and the grandeur of Nature – maybe even a little humility – and I guess I wouldn’t argue with that. But in the end surfing, in my opinion, does little or nothing to build or improve character. As we all know, a lot of assholes surf, and some of them surf well.”

On the plus slide, “a lot of my best friends surf, and it can be a great deep thing to share with people you really like,” he wrote. “Non-surfers are certainly never going to understand it.”

Finnegan’s been a staff reporter at The New Yorker since 1987. No one reports better than the New Yorker. How, I asked, could surfing be reported better?

“I’m not a press critic,” he wrote. “But what I do read is way too advertiser-friendly. BeachGrit seems to be an exception. (Am I right?) Readers can smell where a mag’s loyalties lie, and if those are not largely with the readers, everybody knows it. Surfing is an unusual journalism niche because the interests of the surf industry, which very largely finances the surf media, are fundamentally at odds with the interests of most surfers, at least as I understand them. They want to ‘grow’ the sport. We’d like it to shrink, reducing crowds.

“So we look at mags that are obviously in bed with the corporations trying to sell us stuff – and always trying, naturally, to find more customers – and we know that those mags are in some basic way not on our side, and that they will never take an honest, independent look at those corporations – at their reliance on Chinese sweatshops, say, to produce boards, board shorts, etc, just to take the most obvious example.

“Not every surfer is concerned about sweatshops, of course, but the journalistic bad faith underneath the relationship between most glossy surf mags and their readers has a stench that, at some level, everybody over the age of 12 is aware of. It’s simply not a straightforward relationship. They’re not just trying to entertain and inform us. They’re trying to sell us shit, and not only through the ads but through editorial. Now let me see if I can find my way off this soapbox without turning an ankle.”

Buy Barbarian Days here.

Subscribe to The New Yorker here.