So good you'll weep!

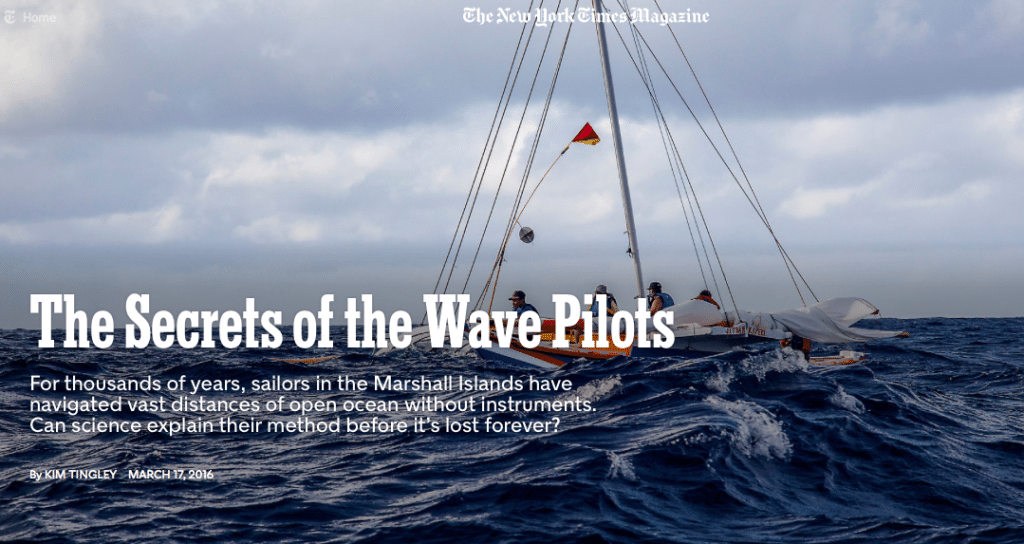

Open ocean navigation fascinates me. Have you ever been far out to sea, playing against wind, tide and swell, pointing at some dot on a computer screen and trusting that it is your port? It always feels amazing to actually arrive. To have beaten back expansive uncertainty and be where you set out to be.

But do you know what astounds me? To do the same thing using only stars, sun and moon. Have you heard of the Hawaiian vessel Hokulea? They are doing the almost unthinkable by sailing without modern instrument around the entire world. It is a story that brings a gasp to even the most hardened cynic’s lips.

I read one better today though. The story of the ri-meto from the Marshall Islands. Pour a drink and enjoy.

At 0400, three miles above the Pacific seafloor, the searchlight of a power boat swept through a warm June night last year, looking for a second boat, a sailing canoe. The captain of the canoe, Alson Kelen, potentially the world’s last-ever apprentice in the ancient art of wave-piloting, was trying to reach Aur, an atoll in the Marshall Islands, without the aid of a GPS device or any other way-finding instrument. If successful, he would prove that one of the most sophisticated navigational techniques ever developed still existed and, he hoped, inspire efforts to save it from extinction. Monitoring his progress from the power boat were an unlikely trio of Western scientists — an anthropologist, a physicist and an oceanographer — who were hoping his journey might help them explain how wave pilots, in defiance of the dizzying complexities of fluid dynamics, detect direction and proximity to land. More broadly, they wondered if watching him sail, in the context of growing concerns about the neurological effects of navigation-by-smartphone, would yield hints about how our orienteering skills influence our sense of place, our sense of home, even our sense of self.

When the boats set out in the afternoon from Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, Kelen’s plan was to sail through the night and approach Aur at daybreak, to avoid crashing into its reef in the dark. But around sundown, the wind picked up and the waves grew higher and rounder, sorely testing both the scientists’ powers of observation and the structural integrity of the canoe. Through the salt-streaked windshield of the power boat, the anthropologist, Joseph Genz, took mental field notes — the spotlighted whitecaps, the position of Polaris, his grip on the cabin handrail — while he waited for Kelen to radio in his location or, rather, what he thought his location was.

The Marshalls provide a crucible for navigation: 70 square miles of land, total, comprising five islands and 29 atolls, rings of coral islets that grew up around the rims of underwater volcanoes millions of years ago and now encircle gentle lagoons. These green dots and doughnuts make up two parallel north-south chains, separated from their nearest neighbors by a hundred miles on average. Swells generated by distant storms near Alaska, Antarctica, California and Indonesia travel thousands of miles to these low-lying spits of sand. When they hit, part of their energy is reflected back out to sea in arcs, like sound waves emanating from a speaker; another part curls around the atoll or island and creates a confused chop in its lee. Wave-piloting is the art of reading — by feel and by sight — these and other patterns. Detecting the minute differences in what, to an untutored eye, looks no more meaningful than a washing-machine cycle allows a ri-meto, a person of the sea in Marshallese, to determine where the nearest solid ground is — and how far off it lies — long before it is visible.

In the 16th century, Ferdinand Magellan, searching for a new route to the nutmeg and cloves of the Spice Islands, sailed through the Pacific Ocean and named it ‘‘the peaceful sea’’ before he was stabbed to death in the Philippines. Only 18 of his 270 men survived the trip. When subsequent explorers, despite similar travails, managed to make landfall on the countless islands sprinkled across this expanse, they were surprised to find inhabitants with nary a galleon, compass or chart. God had created them there, the explorers hypothesized, or perhaps the islands were the remains of a sunken continent. As late as the 1960s, Western scholars still insisted that indigenous methods of navigating by stars, sun, wind and waves were not nearly accurate enough, nor indigenous boats seaworthy enough, to have reached these tiny habitats on purpose.

Archaeological and DNA evidence (and replica voyages) have since proved that the Pacific islands were settled intentionally — by descendants of the first humans to venture out of sight of land, beginning some 60,000 years ago, from Southeast Asia to the Solomon Islands. They reached the Marshall Islands about 2,000 years ago. The geography of the archipelago that made wave-piloting possible also made it indispensable as the sole means of collecting food, trading goods, waging war and locating unrelated sexual partners. Chiefs threatened to kill anyone who revealed navigational knowledge without permission. In order to become a ri-meto, you had to be trained by a ri-meto and then pass a voyaging test, devised by your chief, on the first try. As colonizers from Europe introduced easier ways to get around, the training of ri-metos declined and became restricted primarily to an outlying atoll called Rongelap, where a shallow circular reef, set between ocean and lagoon, became the site of a small wave-piloting school.

In 1954, an American hydrogen-bomb test less than a hundred miles away rendered Rongelap uninhabitable. Over the next decades, no new ri-metos were recognized; when the last well-known one died in 2003, he left a 55-year-old cargo-ship captain named Korent Joel, who had trained at Rongelap as a boy, the effective custodian of their people’s navigational secrets. Because of the radioactive fallout, Joel had not taken his voyaging test and thus was not a true ri-meto. But fearing that the knowledge might die with him, he asked for and received historic dispensation from his chief to train his younger cousin, Alson Kelen, as a wave pilot.

READ THE REST HERE!