Ballistic missiles head for Hawaii. Then they don't.

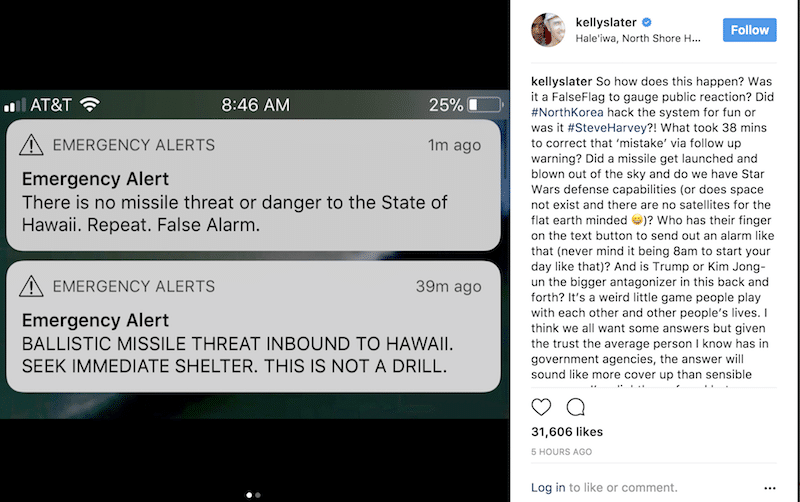

(Earlier today, Hawaiians were told via SMS that they were under attack from ballistic missiles. Twenty minutes later another SMS let the terrified populace know it was a false alarm. “I hid in a basement and told my family how much I love them because I thought we might only have another five minutes to live,” wrote Jon Pyzel, shaper to John Florence. “I will never forget that feeling nor will I forgive the leadership that put us in that position.” Kelly Slater railed, “So how does this happen? Was it a FalseFlag to gauge public reaction? Did #NorthKorea hack the system for fun or was it #SteveHarvey?! What took 38 mins to correct that ‘mistake’ via follow up warning? Did a missile get launched and blown out of the sky and do we have Star Wars defense capabilities (or does space not exist and there are no satellites for the flat earth minded 😀)? Who has their finger on the text button to send out an alarm like that (never mind it being 8am to start your day like that)? And is Trump or Kim Jong-un the bigger antagonizer in this back and forth? It’s a weird little game people play with each other and other people’s lives.”

It’s these moments, when death looms, that the fragility of life and the importance of relationships and health, is put into sharp relief. Suddenly, money and bullshit don’t mean so much.

Printed below is a story I wrote for Warshaw’s book Zero Break: An Illustrated Collection of Surf Writing on the importance of grace. Sometimes it doesn’t hurt to step away from the hammer and the blowtorch.)

Meet Michael. Twenty three. Perpetually untidy dark brown hair. Doesn’t work. Enjoys nothing more than sitting around with his pals filled by a lungful of pot smoke and watching the latest surf clips. Reads surf mags cover to cover and thinks all the girls in bikinis are pretty hot. An average surfer, you’d reckon.

He would be except Michael has never surfed. Never will. When he was nine he dived off a jetty and into a shallow sandbar. The impact crushed the vertebrae in his neck. Hasn’t felt a thing in his arms, torso, legs or, if you’re wondering, his dick for fourteen years. Lives in a Melbourne nursing home, shits and pisses in a bag that hangs over his wheelchair and that has to be emptied by the nurses he’d love to kiss, hold, fuck, if he could feel anything. He’ll probably die of the usual complications that afflict the paralysed, infection, liver malfunction, in twenty or so years. A good guy but prone, understandably, to depression and drug abuse.

He watches with quiet awe as surfers duckdive their boards. How incredible it must feel to have a wave pass over your back and to surface into the bright tropical sun. And how amazing it must be to view the world from inside the tube.

When he gets his hands on a long-form surf movie his life changes. The grim grey and metal surroundings of his ward fade away as he enters the cool blues and greens of the ocean. He watches with quiet awe as surfers duckdive their boards. How incredible it must feel to have a wave pass over your back and to surface into the bright tropical sun. And how amazing it must be to view the world from inside the tube.

At night he dreams that his body works. Dreams of paddling into a Grajagan boomer, the spray blinding him for a moment only to clear as his tail lifts and he drives down the face and begins his hunt for the tube.

Michael thinks about death a lot and would like to commit suicide. He is jealous that others have the luxury of being able to hold a gun or throw a rope over a rafter. He imagines dying will be like finally breaking the tape after an endurance race. He pictures a heaven, paradoxically he thinks God is a hoax, where his legs are strong and his arms power him and his surfboard through the water.

But when he wakes, he’s a man in a wheelchair. No magic cures.

Along with a few movies, I gave Mick a miniature plastic surfboard for Christmas. Another joy. He puts it on his table and uses a pen in his mouth to move it around, banking off imaginary wave sections like a tiny Kelly Slater.

His family doesn’t visit much anymore. More often than not, Mick’s a bit of a trial to be around. He knows that. He’ll cry at the smallest thing, like his seven-year-old cousin Lisa giving him a drawing she did in school and he’ll overreact if he thinks he’s being patronised. Mick regrets it after but it leaves everyone pretty upset.

Michael thinks about death a lot and would like to commit suicide. He is jealous that others have the luxury of being able to hold a gun or throw a rope over a rafter. He imagines dying will be like finally breaking the tape after an endurance race. He pictures a heaven, paradoxically he thinks God is a hoax, where his legs are strong and his arms power him and his surfboard through the water.

I write about Michael only to serve as a reminder of how lucky we are to be able to go surfing. Happiness, I’ll agree is relative, but I see guys slapping the water, yelling at everybody to fuck off, flicked boards, grommies throwing a fit because they lost a surf contest heat, punches thrown at even imagined slights and grown men nearly in tears because the wind or the tide is wrong and I think…

Jesus, if you only knew…