It works, mostly, depending on the "motivational state of sharks."

Have you ever dreamed of owning a small slice of a cutting-edge technology company? One that is not only a game-changer but actually saves human lives? And, best of all, is a growth industry?

One week ago, the Australian company Ocean Guardian Holdings, formerly Shark Shield, threw open its doors with an IPO (initial public offering, means they’re selling shares in the company) in the hopes of moving 25 million shares at 20 Australian cents apiece in its go-away-shark biz.

Shark Shield, if you were wondering, is one of the few technologies that has been independently proven to work, at least some of the time.

According to The Australian,

The technology behind the Shark Shield Freedom+ Surf has been shown to deter great whites from potential prey. Many divers in South Australia swear by them. The device emits electromagnetic pulses up to 2m. These pulses are detected in the sensory organ in the shark’s head called the ampullae of Lorenzini, making the shark uncomfortable. But the findings into the device’s effectiveness are inconclusive, especially in situations when the shark is in attack mode. Also, two people have died while wearing the device.

Abalone diver Peter Clarkson was wearing a Shark Shield designed for divers when he was killed near Coffin Bay, South Australia, in February 2011. He was known to switch his device on at all times while diving but nobody knows for certain whether he did so on this occasion.

Paul Buckland was wearing a SharkPOD, an earlier version of the Shark Shield, when he was attacked and killed off Ceduna in April 2002.

At the subsequent coronial inquiry, it was concluded that he had not turned the device on when he dived into the water. He reached the bottom and was collecting scallops when a shark started buzzing him. He turned the device on and swam to the surface. Once on the surface, the device’s effectiveness was reduced. He was then attacked.

Senior Sergeant RB McDonald, of South Australia’s police water operations unit, told the inquiry that such devices have “little effect” once a shark has reached a “level of excitement where it will attack”.

Asked after this week’s launch whether he agreed with this, Shark Shield managing director Lindsay Lyon said: “Look at the independent scientific research that shows that Shark Shield is capable of deterring a shark charging at … full speed.”

The research Lyon refers to was conducted by Charlie Huveneers off South Australia in 2012. A seal decoy was towed behind a boat at 10km/h. Great whites approached the decoy as if to attack and were seemingly deterred by the Shark Shield, but their speed was not recorded. The commonly agreed top speed of great whites is 40km/h but one researcher has estimated one travelling at 56km/h.

Huveneers also noted that the Shark Shield “did not deter (great whites) in all situations”, and that the effectiveness of the Shark Shield depended on the “motivational state of sharks”.

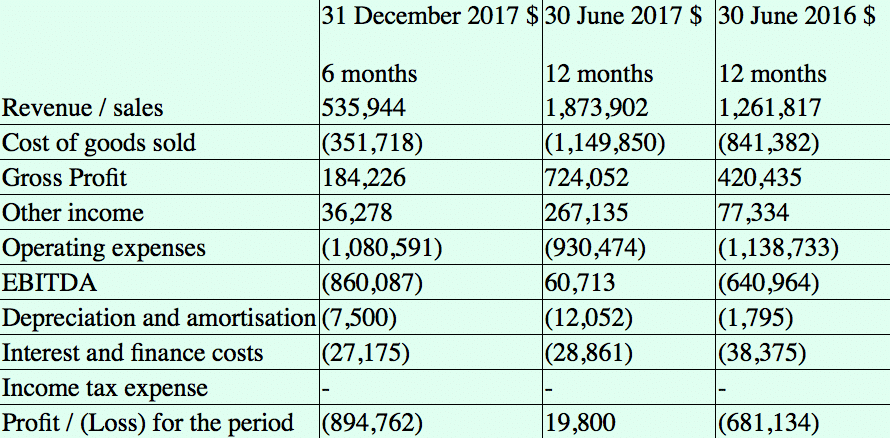

The inner-motivations of Great Whites aside, let’s examine the company’s books.

Is it viable biz? Is it worth throwing your lunch money or your life savings at?

Ain’t much profit dripping down, those big numbers in brackets down the bottom are losses, that twenty-gees in the middle is a real slim make on almost two million dollars of sales.

The company wants to raise capital, it says, to expand into the leisure boating market (who wants to see y’kid swallowed as she gets towed behind on her inflatable banana?) as well as investigate new long-range shark deterrent technology.

(Actually, $750,000 will be the cost of the float, $1.2 mill will be spent on marketing and only $1.5 mill be spent on research.)

Interestingly, the technology behind Shark Shield has been off-patent since 2016 meaning you could, theoretically, save your cash and start your own go-away-shark biz with Shark Shield technology.

In? Out? Snake oil or no?