"Capitalism, on the other hand, absolutely wants to sell you more stuff, is searching for more consumers to sell to and just loves attention." Oh it's a real tug-o-war!

Despite the ruckus in the surf industry, surfing is very much alive and chugging along nicely, thank you, oblivious to most of the drama that surrounds the long-running mismanagement of surfing as an industry.

So why all the bad news?

The Hurley debacle is getting most of the press these days but really it’s been a long slow burn going all the way back to the late-eighties when Quiksilver first took their company public.

Let us try to explain.

Surfing, by its very nature, inherently contradicts basic capitalism.

Surfers, for the most part, don’t need more stuff, don’t want more surfers, don’t care about grabbing attention, etc.

Capitalism, on the other hand, absolutely wants to sell you more stuff, is searching for more consumers to sell to and just loves attention.

Juxtaposed, you might say.

So, when Quik put the company up for public trading they inadvertently entered into a different way of doing business of which the company, and in turn, much of the surf industry, has never really overcome.

Ya see, publicly traded companies, or even those propped up with significant amounts of venture capital funding, are expected to produce a profit.

Full stop.

The CEO will quickly be shown the door if they are unable to create those profits. Those gains usually come through increases in top-line revenue, but can also be helped through improved operational efficiencies.

Since revenue is often seen as the easier of the two it gets a lot of attention. Open up more wholesale accounts, expand global distribution, and create new product categories, are some of the ways a company might do that.

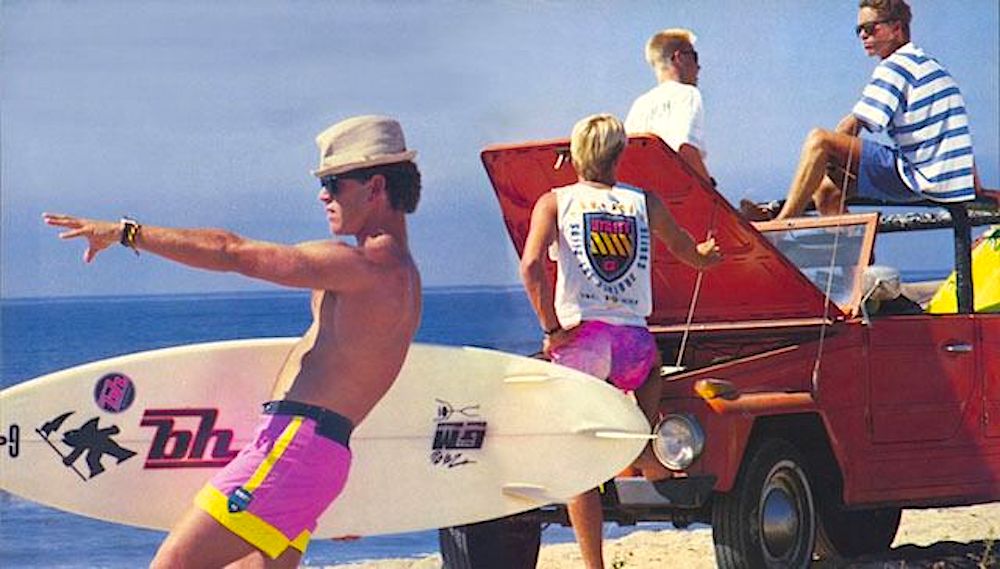

Quik was on it back then and through most of the late-eighties and early nineties, they did all of those things, and more, to quickly blow past 100 million dollars in annual sales. That was a huge number back then and at the time that growth was readily available simply because there was so little competition and the emerging wholesale channels were also beginning to flourish.

“Surf” was hot and Quik was right there with everything one might have needed to complete the look.

You could pretty much go head to toe in Quik gear.

And many did.

As was predictable, the surf trend waned and that double-digit growth that the surf brands were achieving suddenly became more challenging.

Over these early years, many of the major surf brands had begun gearing up to produce the massive amounts of product the trend required.

But with the core surf market being fickle, creating new categories was quickly recognised as needed to maintain that investor mandated growth.

Wetsuits, snow gear, women’s lines, kid’s products, middle-aged guy stuff, accessories like watches, sunnies, and sandals, were all quickly included in almost every surf brand’s offerings. “Stay in your lane” be damned.

Believe it or not, there was once a day when Quik just made great boardshorts, O’Neill made great wetsuits, Oakley made the sunnies, etc.

Soon, however, it seemed like all brands were in literally every category, unfortunately, not always doing that with much quality.

This corresponded with an almost across the broad removal of much of that vital, creative, entrepreneurial spirit as brands rotated the founders out and rotated in a revolving door of CEOs trying to catch lightning in a bottle one more time.

Without any semblance of connection to their customer base, this led to an almost industry-wide lack of a fundamental understanding of who their most important customer really is.

Which fed into the very destructive miscalculation that a core fifteen-to-twenty-five-year-old surf consumer doesn’t mind wearing the same brand as his kid brother, sister or even his dad.

They didn’t understand that filling off-price, big-box retailers with crappy products might actually damage the commodity.

They simply didn’t realise that actual surfers don’t really need a bunch of stuff.

Surfing is just a thing we do. Period.

Surf clothing, and much of the other gear being peddled today, isn’t really required to actually surf so to achieve the growth big brands require much of the consumer base needs to be non-surfers.

It’s a pretty simple concept really: A brand employs various marketing tactics to use surfing as a way to appear cool to a non-surfing consumer.

But what happened, instead, was that the truly influential young crew on virtually every beach were no longer connecting to that message and they began to walk away from most surf brands.

Gotcha is long gone.

Volcom has changed hands numerous times.

Quik and Bong were both bought for pennies on the dollar and are now owned by the same VC firm.

O’Neill is owned by a European investor that has licenses for the clothing and wetsuits.

Rip Curl, the last of the privately held “big brands” was recently sold to a large conglomerate.

Reef, Vans, Oakley, BodyGlove, etc, have had significant ownership changes over the years.

And, of course, we all know about Hurley by now.

Which brings us to today.

We don’t know what will come of many of these brands when it all settles out but the early indications appear that there may be some more pain to come.

Then again, maybe this is exactly where we need to be?

Refocusing on brands that communicate to us authentically.

Backing surfers who represent our sensibilities, and living a lifestyle as a surfer of which we define, not some ad agency from Chicago.

Sadly, there are a lot of good people without a job and/or sponsorship today in part because of situations they didn’t create.

They worked hard, drank the company “Kool-Aid,” so to speak, and then when those at the executive level mismanaged the brand, these same good folks got unceremoniously shown the door.

Hopefully, all of them will quickly find gainful employment in less volatile situations.

The unfortunate reality being that this needed to happen.

So no, surfing isn’t dead. It just doesn’t want anything to do with the box the industry keeps trying to put it in.