Carry a tourniquet, learn how to use it, maybe save a life.

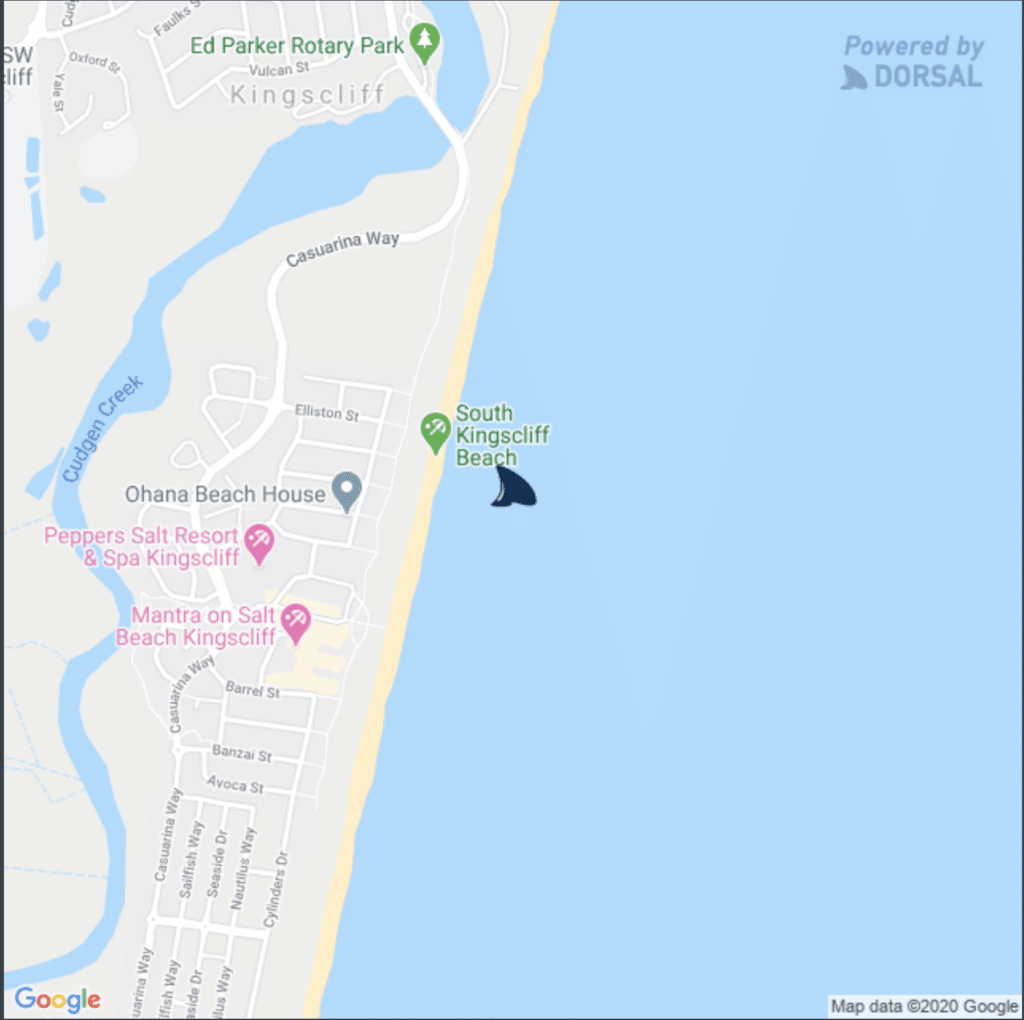

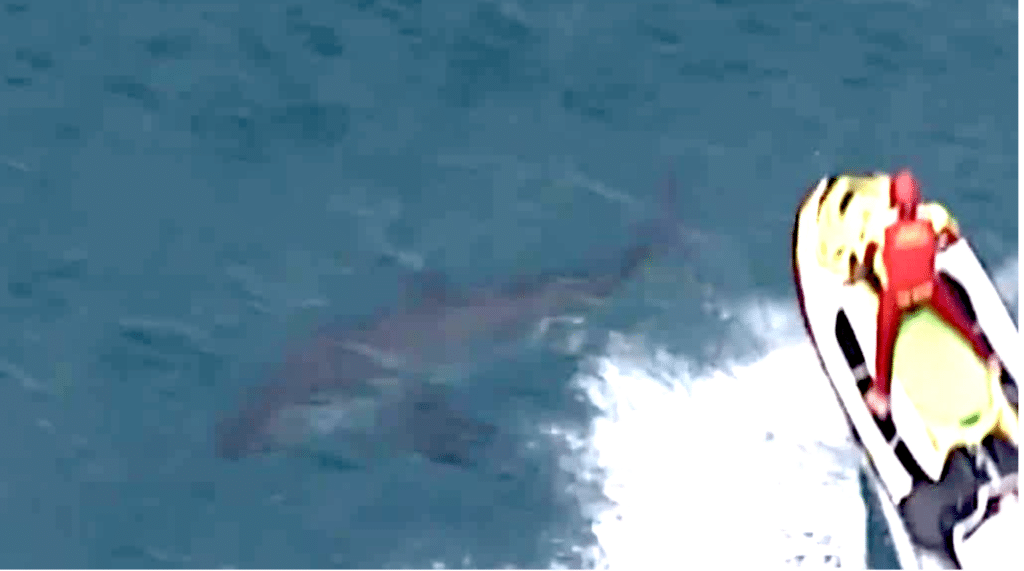

When Gold Coast surfer Robin Pedretti was hit and killed by a Great White yesterday, even after his buddies belted the shark and got him to the beach conscious, it brought into relief the new reality that if you wanna surf certain joints, carry a tourniquet.

Last night I spoke to Jon Cohen, an ER doctor who repurposes military tourniquets for use in the surf and who has made it his mission to use his expertise the solve the problem of preventable shark attack deaths.

He knows that most Great White hits are a bite-and-release taste test so once the shark leaves, if you’re quick a life can be saved.

Cohen, a Canadian who learned to surf in Hawaii, works around Australia in various emergency departments, including Esperance, a sudden hotspot in Great White attack fatalities.

He says he hasn’t analysed yesterday’s attack, so he’s speaking generally, but if you can get a tourniquet above the wound site, your buddy has a good chance of living.

There’s an exception here.

If the shark takes off an entire leg or arm and there’s no stump, well, even a combat medic can’t stop the bleeding.

But if there’s a stump, there’s a chance, a good chance.

If you act fast.

You carrying a tourniquet in your wetsuit? Or on the beach?

Before anything, before calling anyone, get it on, tight, a couple of inches above the joint.

That’s it.

No tourniquet or it’s in the car?

Get a towel. Apply as much pressure as you can where the blood is coming out. All that matters is stopping the blood.

A catastrophic attack and your buddy is going to lose consciousness in three minutes; after five minutes the outcomes are poor, says Cohen.

“Once someone goes into hypovolemic shock a cascade of bad things happen in your body. It decreases your chance of survival,” says Cohen. “In all of the tactical combat critical care, in military areas, wherever there’s mass casualties, big shootings, bombs, massive car crashes, the only thing that’s indicated to do before anything else is to get on the tourniquet.”

Right now, Cohen is working with an ocean safety group in Esperance, a pretty Western Australian town that’s been hit by three Great White attacks in the last six years. Two dead, including a teenage girl, and a man left without an arm and hand. (See Gary Johnson, killed Jan, 2020, teen surfer Laeticia Brouwer in 2017, and Sean Pollard, 2014.)

At a recent seminar teaching Shark Bite Management in Esperance, eighty people turned up.

People carry custom kits in their cars with a sticker on the back that says “Tourniquet Trained”.

I ask Cohen, if being trained in the use of tourniquets is the new CPR.

“There’s still going to be a lot more people during of heart attacks, and that’s true in the surf,” he says, “But if you’re surfing with your family, your kids, some group of buddies, getting the crew together to make sure they know what to do, giving it thought, having a strategy of what to do is part of your risk assessment when surfing sharky spots.”