"Most reasonable people would agree that the only way to significantly reduce the rate of shark attacks is by killing the most dangerous sharks."

There is talk of a promising new solution to Australia’s Great White crisis.

Using technology developed for commercial fishing, standard drum lines would target the most aggressive sharks, by surrounding the bait with an electric field that deters less aggressive sharks.

Each species of ‘dangerous’ shark includes many individuals that are probably not all that dangerous. This might explain the occasional video of a placid ‘man-eater’ swimming perilously close to surfers.

It might also explain the statistical insignificance of shark attacks compared to other public health risks. After all, the number of sharks biting people cannot exceed the number of shark attack victims.

Clearly, most ‘man-eaters’ are not interested in attacking people.

So, the problem is not the species of shark, but the few aberrant individuals that give the species a bad name.

French shark scientist, Eric Clua suggests that; “Selective removal of problem individuals following shark bite incidents would be consistent with current management practices for terrestrial predators, and would be more effective and more environmentally responsible than current mass-culling programs.”

But, why not get rid of the problem individuals before they attack?

Besides, the complete removal of dangerous individuals would have the glorious effect of altering the gene pool and thus taming the species forever. Then, all the shark nets could be removed, to allow whales, dolphins and sea turtles to travel freely, without getting tangled in a net and drowning.

Some environmentalists will abhor the new method of preventing shark attacks, because they impulsively dismiss any attempt to control nature. But, they will disguise their hatred of humanity, with a plausible explanation for how the ecosystem depends on these few ‘alpha-predators’ to stabilise the ecosystem; like claiming that the occasional shark attack is a small price to pay for controlling the population of the Humboldt squid, a potentially more terrifying creature.

One way or another, humans will be sacrificed for nothing but the symbolic value of giving nature free rein. Our predicament is a potent element of their belief system.

In the meantime, we need to address the problem of shark attacks.

Luckily, there is a solution, and it is a surprisingly simple one. The problem is that politics nowadays is governed by emotional outbursts. As a result, we suffer from an overly emotional attachment to nature. This seems appropriate to the Western mind nurtured on a religious diet of environmentalism.

But, compassion is, first and foremost, an emotion felt for people. It is an abomination to value nature at the expense of humanity.

It can be frustrating when people nonchalantly disregard the horror, with flippant remarks that essentially blame victims for being attacked.

But, it is hardly worth worrying about.

People generally don’t think things through. It is the easy answer to a contentious issue. What is worrying, is when people in positions of authority, who are paid to serve the public on this very issue, fail to appreciate the gravity of the situation.

New South Wales’ Department of Primary Industries (DPI) refuses to accept the many flaws in their approach, having just received eight-million dollars to continue a program that offers next to no benefit to the surfing community.

They claim, for example, that tagging sharks helps to reduce the risk of attack, because sharks tend to avoid the coast for many weeks after the traumatic experience of being tagged.

On the face of it, this seems like a reasonable assumption, until you realise how unlikely it would have been for any of these sharks to have attacked someone, had they not been diverted out to sea. The temporary removal of an occasional shark is hardly worth mentioning.

I am not against tagging for sake of research.

Ultimately, I think the program could help to reduce the rate of shark attacks.

But, we would need many more listening stations, maybe ten times as many. However, the purpose of the listening stations should not be to inform the public every time a shark has been detected. The odd shark swimming within range of a listening station just isn’t noteworthy.

What the public needs to know is if the rate of shark detections has increased to a level that indicates a possible trend and thus greater risk of shark attack.

Dr Moltschaniwskyj explained that the rationale is moreso to remind the public that sharks are part of the ocean. So, we agree that the actual presence of the shark does not represent an imminent threat to be avoided.

Even in the Lennox to Ballina stretch, where we have the highest concentration of listening stations, these random detections would be a small fraction of the number of sharks in similar proximity to surfers at any time. My guess is that most surfers don’t bother with the service, since most of the sharks passing through the area go undetected.

If that is true, then the alerts only serve to torment people who rarely enter the water anyway, including mothers who worry about their kids every time a shark detection gets circulated on the net.

The new drone technology is impressive. But, it will only ever be deployed at a small fraction of surf spots, and for a small fraction of the time people surf. So, I do not believe that drones will reduce the rate of shark attacks.

Our most recent fatality, fifteen-year-old Mani Hart-Deville, was surfing at a remote location that is probably too remote to justify the funding of drone surveillance. There is also the problem of murky water affecting visibility.

I suggested to Dr Moltschaniwskyj that the DPI might consider surveying the surfing community to find out how many people were actually using the service that notifies users whenever a shark has been detected.

I thought I was talking their language. But, there was no response.

I don’t blame her; because, in some sense, not replying speaks volumes. I probably wouldn’t reply either, if my livelihood depended on toeing the line.

Who knows what people really think these days. We are all hemmed in, one way or another. I have copped a lot of flak for speaking up. So, I generally avoid the topic. But, it is very concerning that two reasonable people are unable to communicate freely about such a significant public concern.

Apart from drawing attention to possible limitations in their approach, I also suggested that they focus on developing a model that predicts the risk of encountering a shark. It is not good enough to randomly remind surfers that sharks are a potential menace. All this does is transfer responsibility to the eventual victims: “I told you there were sharks out there!”

Besides, surfable conditions are rare. The surfing lifestyle requires taking advantage of every opportunity. So, the perceived risk only becomes relevant for a few sorry weeks after an attack.

One attack makes you wary.

Two attacks make you nervous.

It’s not very sophisticated.

A scientifically informed model would assess the risk, based on environmental factors, like ocean temperature, rainfall, proximity to river mouths, whale migration, time of day, and trends in tagged shark movements. Shark scientists have alluded to the potential for such a formula.

Ideally, all known risk factors would be condensed into a simple format that could be read at a glance: i.e. Low, Medium, High, etc. Although costly, physical signage would be more effective than an app, despite the apparent convenience of smartphones. You can’t expect everyone to be fastidious in their monitoring of the shark situation.

I think most reasonable people would agree that the only way to significantly reduce the rate of shark attacks is by killing the most dangerous sharks. Theoretically, this could be achieved with almost clinical precision using an extensive array of electrified drum lines targeting only the most aggressive individuals.

Policy makers can fret over how many sharks the electorate will tolerate being dispatched each year. But, at least they can report with some confidence that the screening process is stringent: sensitive sharks will be turned away.

Eventually, these desperately sad tragedies could become a distant memory.

To be honest, I have no evidence of this technology being taken seriously. For all I know, DPI has scoffed at the suggestion.

It is loosely based on technology designed to protect baited hooks from sharks. So, it might not be patentable.

But, I have applied for a patent, just in case.

The opportunity is lost, once it goes public.

After submitting the application, I wrote to the Minister responsible for DPI’s operations, asking that he present it to DPI on my behalf.

But, I am afraid he is also having difficulty penetrating DPI’s fortress mentality.

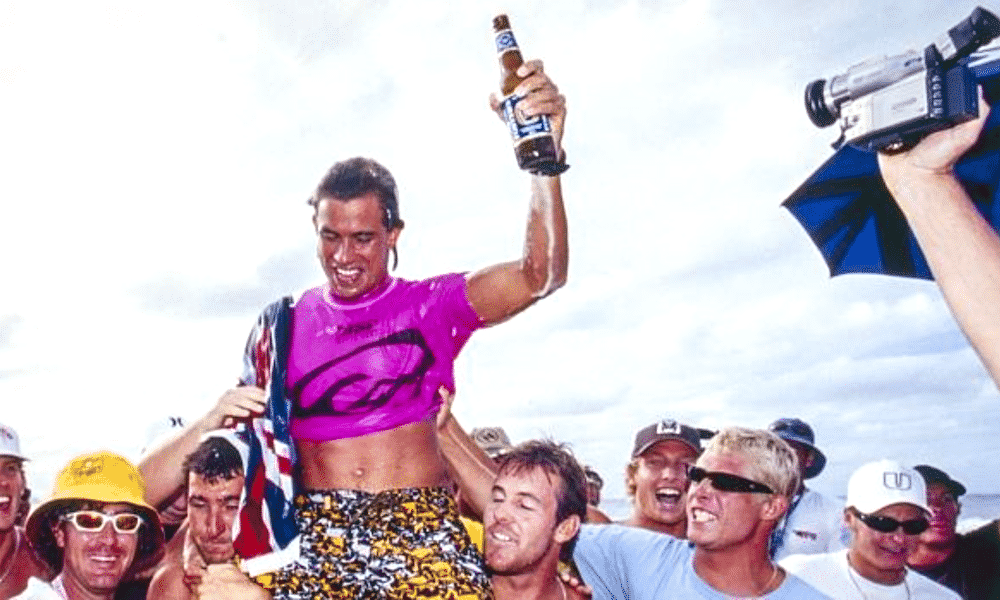

(In 2016, Dan Webber watched as surfer Cooper Allan got what is described on the north coast as a “Ballina hickey” from a Great White. “I was standing in waist deep water, about five metres away, when I saw a shark in the face of a wave between me and three guys sitting further out,” said Dan. “A few seconds later, I heard a shout, followed by the nose of a board sailing through the air.” He is the author of When Great Whites Take Over Your Beach and Sobering: The (Real) Odds of a Shark Attack.)