"The ocean, always a place of transformative powers with the ability to wash away sadness and depression, now feels foreboding and dark."

I’m lost.

I’ve got two weeks off in the middle of prime surf time on the NSW North Coast: offshore winds, pulsing southerly swells, nominally smaller crowds.

This should be peak surf pig time.

Up early, twice or thrice daily surfs, road trips.

This is accentuated by the fact I’ve now got two surf stoked teens, both on winter school vacay, in tow. Daughter and son both surf bug-bitten.

You remember what it’s like to be a grom. You’ll surf anything, anywhere, anytime.

So week one of the holidays, we had been doing a whole heap of surfing.

Now, this binge of surf piggery has been brought to a shuddering halt by the death of 15-year-old Mani Hart-Deville in a shark attack in a neighboring surf community.

The other end of the stretch of national park that I usually surf.

A student at the school I used to teach at.

Too close to home.

I got the full rundown of the whole harrowing event from a first responder. The scariest, most traumatic shit you can imagine. Made all too real by the similarity in age to my own sprogs and the recounted experience of what the young man’s parents had to endure.

From full throttle to flatlining in the space of a day.

The ocean, always a place of transformative powers with the ability to wash away sadness, anger, frustration, depression and tension with nothing more than a quick dip, now feels foreboding and dark.

I’ve already modified my own surf behaviour, due to the spate of attacks to the north of me in the Ballina/Byron area in years previous. I was on a surf alone at sunrise, out of the water before 7.30 am rotation when that shit all went down. No longer.

When I was a kid, there seemed to be concrete rules for avoiding becoming prey for something built for ocean predation: don’t surf at sunrise or sunset, don’t surf alone, don’t surf in murky water, avoid deep water, avoid reefs and rivermouths.

Now all the old paradigms are out the window.

The weekend attack happened at two pm on a sunny winter’s day. Small beachbreak peaks not fifty metres off the shore.

The same with the majority of the Ballina “cluster” attacks in years previous.

Middle of the day, sunny, fun swells, very inviting.

I’m flummoxed as to how to modify my behaviour any more to avoid an attack. When I say my behaviour, I’m thinking primarily of how I’m going to manage my kids.

If I get hit, I get hit.

I don’t know how I could face the idea of knowing that I put my kids in harm’s way through my example and guidance. A parent’s primary responsibility is to teach and nurture.

To dispense advice and information to help their offspring navigate situations safely.

But how do you protect your kids and yourself from attack, when the evidence is stacking up that it could happen at any time, in any conditions?

While I know it has probably always been this way, it just feels that the dial on the likelihood of a shark interaction here on the North Coast has moved from implausible to distinctly possible.

Two days after the attack I’m at a loss with what to do.

Normally I’d get up, we’d pack the car and go find a wave. Now I don’t want to. Well, I do want to, but I’m hesitant to.

This is the rhythm and rhyme of my life, but now it’s out of sync.

I lag.

I do the washing, tidy the house.

But.

It’s sunny, it’s offshore, a classic winters day. So we pack the car with boards, wetsuits, and towels. Just in case.

We arrive to be greeted with groomed little two-foot peaks under a light offshore. God, it looks tempting.

I bump into an old local. He’s a member of the bite club. Took a hit from a bull shark at the local back beach after a flood, surfing in murky water in 2001. Used a leg rope to tourniquet his thigh, climbed the headland, drove himself fifteen minutes to the local hospital and passed out laying into the horn as he rolled into the emergency bay.

The kids look, wait for me to give them the cue.

Are we going out?

Nope.

Not today.

We walk the beach, climb the headland, continually scan the waves, kick a football on the beach, try to resist temptation.

I bump into an old local, now in his late sixties, still as surf stoked as ever. The number of days he has left to surf are winding down he knows, got to get as many go-outs in as he can before he can’t go out no more.

He’s a member of the bite club. Took a hit from a bull shark at the local back beach after a flood, surfing in murky water in 2001. Used a leg rope to tourniquet his thigh, climbed the headland, drove himself fifteen minutes to the local hospital and passed out laying into the horn as he rolled into the emergency bay.

“You’ll be right to go out” I joke. “What are the odds of getting hit twice?”

“Not today,” he says. “Best to leave it for a bit.”

The rational part of both of us knows that the chances of anyone getting hit today are the same as any other day. But it just doesn’t feel right. It just doesn’t feel responsible for me to allow my kids into that environment, barely twenty-five kilometres and under forty-eight hours from where a kid basically the same age died a traumatic death simply enjoying what my kids want to enjoy right now.

I know all the arguments.

I’ve subscribed and parroted them myself. You’ve got more chance of dying on the way to the beach, you enter their environment at your own risk, a life lived in fear is a life half lived. But today I look at the ocean, and I look at my son and daughter and I just can’t bring myself to allow them to enter the water. Not today.

I know it can’t last.

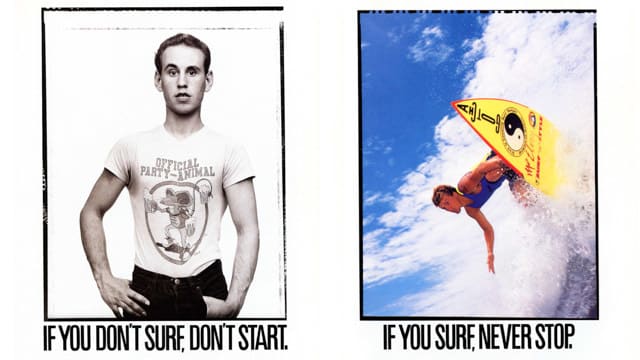

The lure of surf is now as much a part of their lives as it is mine.

And a small part of me now curses that.

Curses the fact that my kids are now infatuated and enamored with this lifestyle and environmental interaction we call surfing.

Mani Hart-Deville, there for the grace of God go I, could have been my son or daughter in the great game of chance that now seems to be the act of surfing on the NSW North Coast.

One day soon, we’ll go surfing again.

We’ll be wary at first, tentative and skittish.

And if we’re lucky, with time things will again begin to feel, well, normal.

The ocean will hopefully become a place again of feeling joy and exhilaration, rather than of trepidation.

I want my kids to still love surfing, to still feel alive in the ocean.

But I don’t want to lose my kids in the ocean, don’t want to see them pulled clinging to life from the sea.