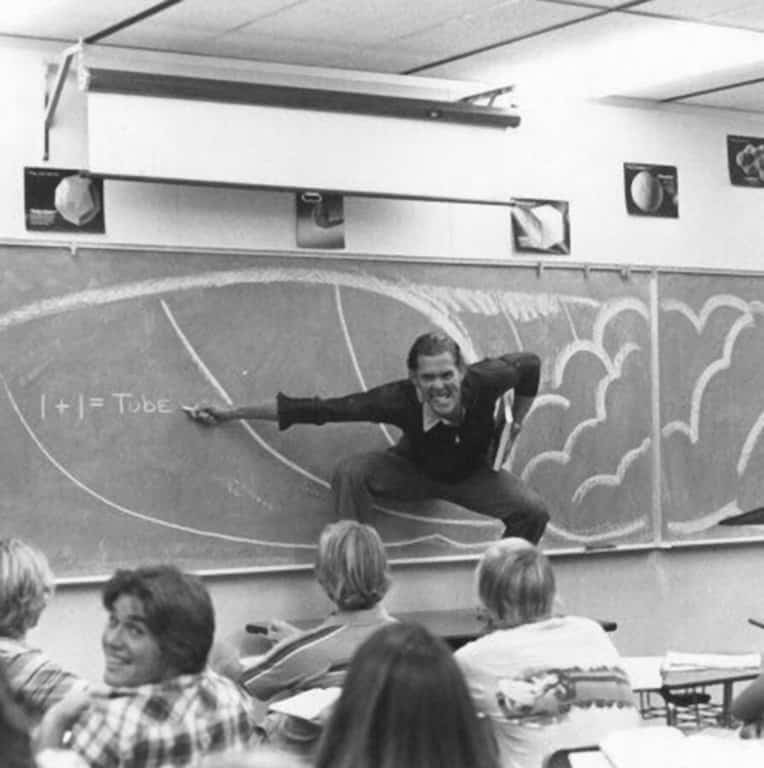

Amateurs surfed against professionals, women against men, sixty year olds against teenagers.

In September of 2001, just as the world was about to fracture live on television, some of the world’s most notable surf personalities met on a remote Scottish island, summoned by Derek Hynd to trial an experimental competition format.

No-where before or since has a contest taken place with such a disparity of wave riders.

Some were pioneers, some were world champions. Others were renegades and surf dissidents. And yet more were plumbers, fishermen and oil rig workers.

Many of them had travelled the globe, surfing the world’s most iconic waves; others had never ventured far from their home breaks.

They rode high performance shortboards, and longboards, and fish, and single fins, and eleven-foot gliders, all in the same heats.

Tom Curren chose to bodysurf some heats, or borrowed local longboards.

Amateurs surfed against professionals, women against men, sixty year olds against teenagers.

It was competitive surfing reimagined, a fusion of art and sport on an ancient shore.

It was an attempt to step back in time, in search of something that had been lost.

It’s mostly been forgotten, or never even heard of.

But at the time it seemed like it might be the beginning of something. In the context of global terror, perhaps it’s unsurprising that it slipped by relatively unnoticed, like a glassy, perfect wave sliding quietly by when your focus is momentarily elsewhere.

I mail Hynd to ask him about it, not expecting much. I’ve never known what to make of him. He’s always seemed to exist somewhere beyond the pale. But I get a response immediately.

Sure, he says, ask away.

With great excitement I do, then I hear nothing.

In the interim I do some digging. The stories I hear increase his mystique.

A month passes. I’m sure my questions have offended him somehow, I’m sure I asked the wrong things.

Then one morning I wake up to an email which begins with an apology for the delay then continues with a thousand words of scattered eloquence.

Personal opinions of Hynd are beside the point, you want to hear what he has to say.

“Either surfing was in good shape by the mid nineties or it’d gone to shit. All depended on perspectives,” he wrote. “One major surfing recession started with Gotcha heading into street and department stores and losing the beach, others positioning themselves to go public, Indo no longer guaranteed jungle isolation with Rip Curl or Quiksilver boats sniffing around, board design in worst ever shape, be it potato crisp crap or flip flap mals. An entire generation… misdirected.”

He tells me he wanted to conduct an event that “refocused the surfing essence”.

The set-up was this: there were three categories, pros, soul surfers (solid amateurs but not quite full pros) and locals.

Each was given a handicap to start according to ability: locals started with +5; soul surfers with +3; and pros on 0. Waves were scored out of 10, best single wave counted.

Everyone surfed together regardless of equipment, ability or gender.

There was a 50/50 split between technique and artistic expression, and a judge for each.

It was non-elimination, scoring was cumulative throughout the event, and there were cash prizes at the end of each day for the best performer.

The claiming rules were as follows: if you finished a ride and claimed it counted as your scoring wave; or you could gamble and claim on take-off which would get you an extra point, but would mean you had to count that wave.

As well as being inclusive and celebrating artistry, the format encouraged performance.

The handicap system meant there was no way of holding back against objectively lesser surfers. The claim system added an intriguing gambling element.

“I think there were two heats in a row where I got a really good wave straight away and I was like ‘just claim’ and there was only five mins gone, it was pretty weird,” recalls Mark “Scratch” Cameron, a Fraserburgh surfer who was twenty-three at the time and had recently won the first of his seven Scottish championships. “But then, you could be in a heat where everyone else has got a wave and you’re in yourself. It was a good idea.”

“Hynd’s format is genius,” the shaper Christian Beamish says. “It brings a level of democracy to surfing competition, and by calling it a ‘Surfing Festival’ the emphasis is on performance and exhibition, more so than a more antiseptic, purely points-awarded-for-moves basis.”

Although it’s often a justified meritocracy, surfing has a socialist core. The playing field is open and free to everyone.

Derek Hynd’s format, trialled in the Hebrides, embraces surfing’s unique connection: we’re all in it together, just trying to get a few waves and ride them how we choose.

“The Hebridean happening took a shot at bringing all surfers together under the common surfing creed: We are as one,” Hynd wrote in Surfer.

I’m curious as to why Hynd’s format didn’t progress.

Everyone I speak to seems to feel that it was an unqualified success. Rumour was that Hynd envisioned this as a precursor to a breakaway tour.

He would hold a series of events, all far from the madding crowd.

“We are looking at holding further events in outlying regions of the world, where it takes a surfers commitment to attend,” Hynd told the BBC shortly after the first event. “The more remote areas appear to have more soul.”

But when I ask him today why it never moved on he tells me that was never his intention. This seems to be the way with Hynd, his ideas, much like his surfing, are like a stream of consciousness. You never know what line he might take next.

“There was no notion of having it progress,” Hynd tells me, nearly 20 years on. “People simply got a kick out of it, or I hope they did.”

Of course, they couldn’t know they would be there, among the crofts, and the wind, and the stones, in an old world, when the new world came tumbling down. It seems frivolous to celebrate the act of surfing against this backdrop, but that’s what they did.

Christian Beamish remembers the night they found out about the attacks in the US and Tom Curren saying that they would change everything. He recalls some confusing reactions.

“One fellow, out from London, watching the Towers fall on repeat on TV that night, started to say, ‘Sorry, but you guys deserve it,’ Beamish says. “That made me really angry, and I recall telling him to shut his fucking mouth.”

But the purpose of the event remained the same. Maybe it had now become even more important to regain community.

“What did come out of it was a sense of spirit and place,” Hynd says.

There was nothing to do but surf. And maybe that was enough.

An image burns in my mind.

A modern world crumbles as an ancient one stands stoic.

Lewisan kneiss stretches skyward. Stones that have stood for hundreds of years, mysterious, immovable and unchanged.

Three thousand miles across the Atlantic, 21st century monoliths vanish into dust clouds and fear.

Concrete and glass and steel and flesh dissolve into chaos as the world looks on.

Some people are surfing.

Eventually, they must return to shore.

But until then, they’re ok.