“Fear on Cape Cod as sharks hunt again!”

Here’s a story eerily familiar to surfers and anyone who goes into the water beyond their shins in Australia.

No Whites around, virtually no attacks in the past one hundred years… suddenly… boom…boom…boom… hits, fatals, surfers bleeding out on the sand.

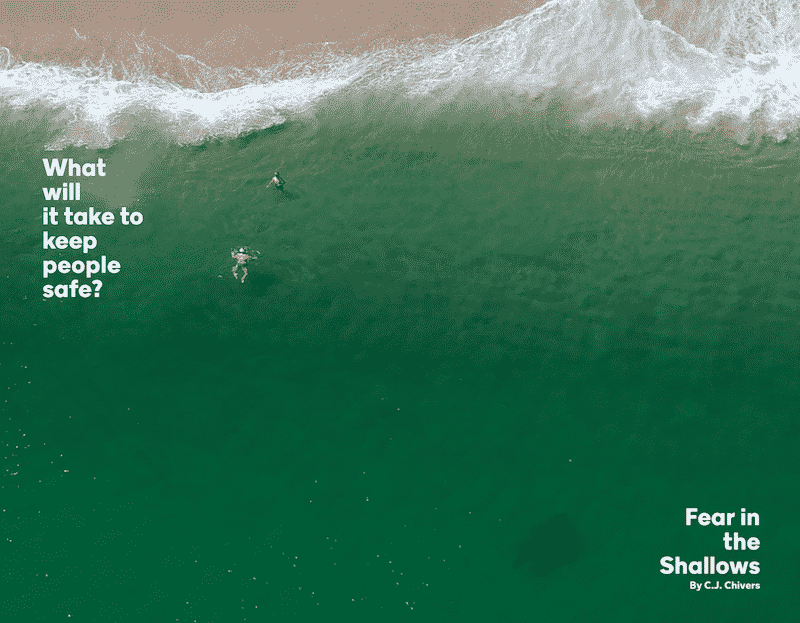

Gorgeous Cape Cod, that geographical cape that swings its J-curved arm from the south-east corner of mainland Massachusetts, think rich cunts festooned in striped tees riding in yachts etc, has suddenly become “host to one of the densest seasonal concentrations of adult white sharks in the world.”

“The animals trickle into the region during lengthening days in May, increase in abundance throughout summer, peak in October and mostly depart by the dimming light and plunging temperatures of Thanksgiving.”

Here’s the numbers: during the entire twentieth century there were three shark attacks, one fatal, in 1936.

Since 2012, there have been five hits by Great Whites.

Last year, a Great White killed a swimmer at Casco Bay, Maine, a couple of hundred miles south.

“In Maine, we never knew we had Great White sharks,” the swimmer’s husband said.

The story is a horror show of first-person accounts.

Here, lifeguard Nina Lanctot arrives to find boogieboarder Arthur Medici, hit by a White, dragged out of the water onto the sand by his pal Issac Rocha.

Medici was motionless and without expression. His pupils were fixed and blank. He was not breathing. She checked his pulse. There was none. Scanning, taking in information quickly, she examined his wounds. A chunk of flesh of one leg was missing, and the other leg was mangled. Worse, the wounds were not bleeding or noticeably seeping. Lanctot’s eyes followed drag marks leading from the water to Medici’s silent frame. There was not a drop of blood. His femoral or popliteal arteries had been severed, she figured, and his blood drained away. Without hemostatic clamps and immediate transfusions, he was past saving. The nearest hospital was more than 30 miles away. Lanctot knew this math. It was bad.

She heard a man in the crowd. “You’ve got to do something,” he said

Rocha had tied a boogie-board leash around one of Medici’s legs. Lanctot slipped the tourniquet around the other, just under his groin, and twisted it tight, clamping quadriceps and hamstring hard to bone. The lifeguards and doctors worked frantically, pumping Medici’s chest with the flat of their hands while one gave mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Lanctot felt pangs of empathy. Medici’s skin was turning ashen. Rocha was inconsolable. She wished his mother were there to comfort him. She held Medici’s hand, hoping he would feel companionship, knowing he could not acknowledge it.

Surfers are referenced later in the piece, which you can read in its entirety here.

After Medici’s death, some surfers switched to stand-up paddle boards, which largely keep limbs out of the water and offer greater visibility. Others, like Lanctot, quit surfing on the Outer Cape. Some kept surfing, but with whistles, so if a shark appeared they could clear people fast.

Whistles!

Scientists have applauded the arrival of the Great White packs,

“The annual returns are a success story, a welcome sign of ecosystem recovery at a time when many wildlife species are depleted.”

So there’s that, I suppose.