But there's a caveat, "You gotta have balls, you can't be fragile… every trip I see sharks at least once."

There is an island in the Pacific that shivers in the shadow of black cliffs three thousand feet high, the sun only fringing the two moss and fern covered mountains a little before midday, a dim violet haze turning gold.

The ear tunes to the the whining and chattering of the sea birds, the boobies, the petrels, the littles shearwaters, the grey ternlets, to the hissing of ocean swells flowing onto thickets of undisturbed reef.

The is air cool and sweet here on this white man’s island, unknown to the Polynesian mariners subsequently sighted and claimed by a British naval vessel en route to its country’s greatest experiment, to land the detritus of its kingdom, the overflow of its prisons, on a southern continent nine thousand nautical miles distant.

But, here, four hundred miles north-east of Sydney, four hundred souls live in deliberate and splendid isolation, untouched by white guilt for there is no ruined indigenous population, many from the same families that were first to build their little farms there. The people live among three thousand acres of subtropical forests, valleys and ridges and plains and mountains with neither snakes nor stinging insects nor land animals that rear on hind legs, bare teeth and threaten.

If you were to visit this island, you’d find your mobile telephone to be a glass and aluminium paper weight. No towers. No reception.

With only a few exceptions, there are no cars.

Too hot? Open a louvred window. Air conditioners are forbidden, along with rubbish dumps and the disposal of household goods.

When a local tires of, say, a couch, by law he’s gotta ship it to the mainland for a thousand bucks.

Recycling is everything and if it don’t turn into mulch in the island’s vertical composting unit it’ll be sent back to Australia.

In little wooden shacks across the island, an honesty system works for fruit and for the hire of snorkelling equipment. Pay your two dollars for an avocado, for a bunch of organic parsley, slice off a ten for your mask, tuba and flippers.

At Government House, a flag, either pink or blue, appears whenever a local has a kid, gender issues yet to wash ashore. All profit from the liquor store is channelled back into community works.

The ocean barely swings from sixty-eight in the winter months to seventy-eight in early spring.

When the naturist prophet Davey Attenborough landed and sniffed around the island’s Providence Petrel sea birds, he called the place “so extraordinary it is almost unbelievable… few islands, surely, can be so accessible, so remarkable, yet so unspoilt.”

Yeah, in some ways, it’s a paradise, in others a brooding isle of nostalgia and bitterness haunted by the ghosts of vagrant spirits.

The surfer, riding a bicycle, surveys his options in one day.

The outer reefs hugging black-water drop-offs; the electric blue beachbreaks that remind the well-travelled of King Island; the deep-water reef pass shadowed by Gower and Lidgbird.

These aren’t world-class reefs, even if you squint hard into a January sun and try and imagine you’re in French Polynesia. Nice for pictures and, like most places, when the pressure of a specific swell direction cuts through the maze of grottoes and fissures it can lead to something the surfer can exaggerate later.

He looks around. A fin cuts the surface amid a school of fish at a four-foot left-hander three hundred yards offshore. It’s too big to be one of the curious reef sharks that’ll shoulder-hop your tubes. Either a mako, a tiger, a whaler. The fin disappears. The school shifts south.

His decision is fairly plain and straight.

He’ll be surfing alone.

***********

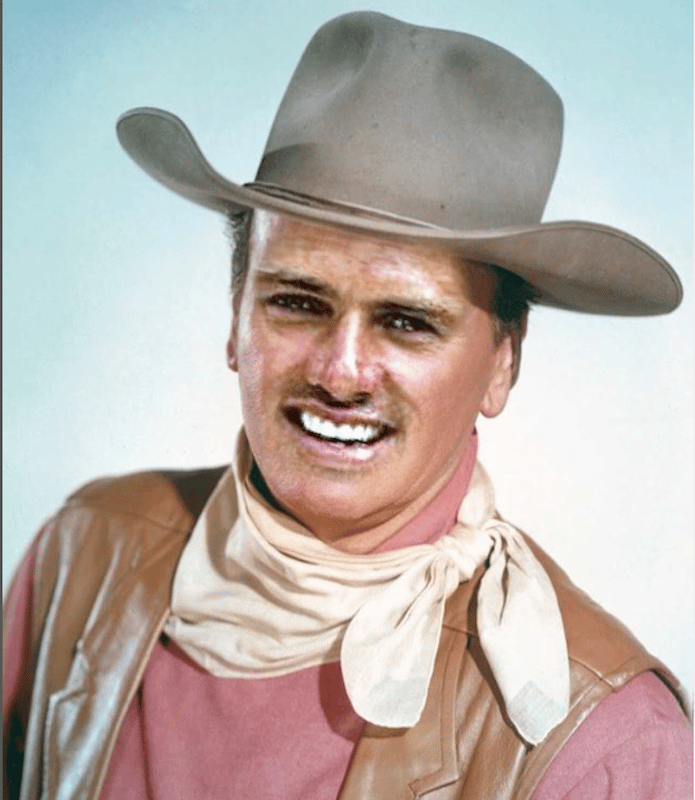

In the Australian spring of 1974, a thirteen-year-old surfer from Bondi Beach, Greg Webber, already three years into the shaping game, walked along the little wooden jetty at Rose Bay on Sydney Harbour to board one of the two Sandringham flying boats, Beachcomber and Islander, that serviced the island.

Thirty years in the sky these birds, converted to civilian by the Royal Air Force use after the war. Basic as hell. The cockpit looked like something out of Dambusters, all levers and wheels and a vast domed windshield.

The two Sandringhams flew, in convoy, to the island, landing in the lagoon, take-off and landing times tidal dependant.

Greg climbed through the starboard door and strapped himself into one of the forty-one vinyl covered seats in the lower cabin, alongside his brother John, fifteen, and his parents, John and Di. (His mom would design the Webber Rorschach logo Greg still uses the following year.) Both brothers had self-made surfboards, single screws, stored in the hold.

The Webbers took the trip on a whim, since it was the last time the birds would fly the island route from the terminal a ten-minute walk from the family house. An airstrip being built on a slab of flat ground near the south end of the island meant regular passengers planes would soon take over.

Greg, now sixty and whose concave heavy designs are still adored by Kelly Slater, remembers the chattering of the finned hull and the side pontoon and flames coming out of the back of one of the motors, the unburnt fuel igniting.

Taking off and landing in water, he says, “was a bizarre and beautiful experience.

The family stayed for one month, the boys doing volunteer work pumping aviation fuel out of 44-gallon drums into storage tanks to prove to the locals they weren’t just “tokenistically pretending to respect them.”

The boys surfed the beachbreaks, Neds and Blinkeys on its eastern shore, ignoring the reefs on the other side of the island.

In 1975, they got the dad of a local kid to take ‘em out to a wave they’d seen flying in, a classic righthand reef pass set up.

“A really sucky, radical sort of wave,” says Greg.

The man’s son was too young to surf so Greg and John broke the cherry on the wave’s four-to-six-foot tubes.

“Surfing those reefs in the seventies was some of the best things we ever did. No one was surfing then.”

Two decades later, big brother John would join Lance Knight, who discovered and named Lance’s Right in the Mentawais, on of his regular supply trips from Yamba to the island on the barge MV Island Trader.

Thirty hours straight listening to the drone of its diesel engines. On a flat-bottomed barge. Open ocean. Hell of a ride.

No glory days of aviation flying boat vibe here.

The island got into Greg’s head, into his brothers’, and it would get into the head of at least one of his sons, who would spend three years of his twenties there.

He likes that it ain’t easy to be a surfer there.

“You gotta have balls, you can’t be fragile,” he says. “You can’t be worried about massive drop-offs, fathoms and fathoms deep, totally black. The guys that fish there know how sharky it is. They pull up their kingfish in a rush. It’s a shit-fight to get ‘em before they’re bitten in half. They get the shortest window before the sharks move in. It’s a beautiful place, but it’s raw.”

Once, some years ago now, Greg decided he wanted to experiment with awareness inside the tube. His gut feeling was, the only thing you can think about inside the tube is the tube itself.

To prove this theory, at least to himself, he would surf nude, and if he was aware of his own nudity inside the tube, well, he was wrong. He paddled out at Middle Beach, did his tube experiment on a little shore break, couldn’t remember being aware of his nudity inside the tube, thus proving his theory.

What he could remember from the tube, however, was some sorta panicked noise. A frenetic splashing.

He looked over and an eight-foot shark is in water so shallow its tail fin was entirely exposed as well as most of his dorsal fin. Maybe two feet of water.

“Every trip there I used to see sharks at least once,” he says.

Ten trips all up, and he lived there for two years in the early two thousands with his wife Christina and boys, Hayden and Joe.

While a resident, a newly retired couple from Brisbane in Queensland arrived on this beautiful and peaceful little isle to celebrate a life without work. The man, Arthur Apelt, seventy years old. One warm autumn night he tells his wife he’s going for a walk. He never comes back.

A few weeks later, a twelve-foot tiger shark is caught, the guts are cut open and out spills Arthur’s head, still with hair.

If you want to get real tough, if your fear glands have been sufficiently cauterised and if you’ll do anything for waves, pay a skipper to take you to Middleton and Elizabeth Reefs, sandy cays sixty or so nautical miles to the north.

“The most horrifying surf trip ever,” says Greg. “Absolutely frothing with sharks. Only two or three people have ever surfed it. A ten-hour boat ride. Reefs in the middle of nowhere.”

The 2016 sleeper hit, The Shallows – surfer hit by Great White, has to get back to shore without being snatched by the jaws of death – was filmed on Lord Howe.

It ain’t all sharks, however, well, not entirely.

The best wave is a joint called Little Island, a wavepool-esque righthander with a tapering shoulder that gets snapped off by the cliffs and edge of Mount Gower. Six-foot on the takeoff that swings into a bowl that you’ll still be telling reporters about thirty-five years after a session you had with your shaper buddies Rodney Dahlberg and Murray Bourton, and nineteen-eighties surfing doc, Narrabeen’s Rod Kirsop.

A lefthander is named after the nineteenth century French warship that lays beneath, La Meurthe, abandoned and sunk in 1907.

But then there’s the stillness of life on the island. The same looks from the same faces. The same inflections at the same point in the same stories told over the same schooners of beer at the same bowling club.

It ain’t for everyone.

“You’ve gotta be able to handle certain levels of quiet,” says Greg. “I could live there for ten years but city people, they could handle one month at the most.”

The secret is to step back, he says, and feel where you are.

“The biggest thing is the fact of the two mountains at the end, Gower and Lidgbird. There’s a certain energy that even really straight, unspiritually minded people will pick up on. First, there’s the three-dimensional aspect, the mountains exist in the background of everything. People visit and are dumbfounded by those mountains, one square and blocky, very male, the other with convolutions and curves to it, female, like a mother and father protecting the islands.”

Greg says he’s going back to the island soon.

He wants to buy there, if he ever gets the chance, houses, which cost in the millions, are offered to residents first, then to approved applicants on a waiting list, wants to live there.

He was told by a local, once, that the Webbers were some of the very few non-islanders who would be welcomed to buy.

“I can’t wait to go back there, I adore the place,” he says. “Old people are very respected there and because there’s no original inhabitants that changes the feeling of being local, which we’re meant to feel guilty about in Australia. But they are… it. That’s why they’ve got this sense of connection to the island that no one can get in Australia. It’s a great place to have a base forever and ever.”

(This story first in The Surfer’s Journal, issue 31.2, with the title, Lonely in the Pacific. Subscribe to that wonderful bulwark against all the bad in the world here.)