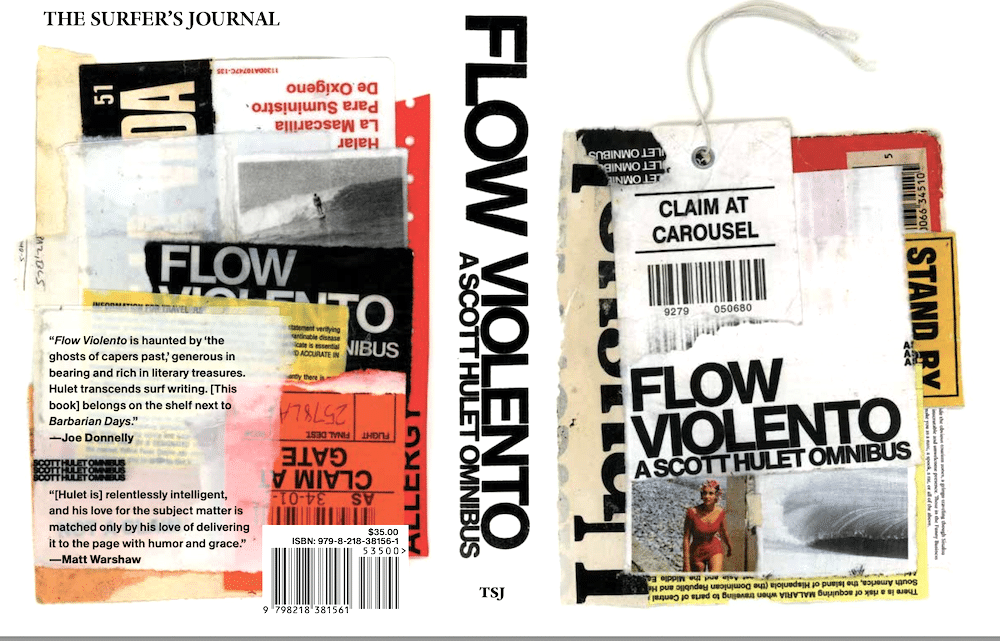

Pick at the bones of long-time Surfers Journal editor Scott Hulet’s dazzling collection of south-of-the-border stories…

The former editor of The Surfers Journal, Scott Hulet, whom you’d swear with his high brilliantined hair, husky voice and sucky mouth was hot silver daddy Gianluca Vacchi, has just released a compendium of south-of-the-border stories accumulated over a thirty-year career called Flow Violento.

To get you warm, here’s a story contained within called Two Dog Circus, “surrealism in central Baja.”

**************

San Quintín sprawls along the highway, debauched and sour, merging with the neighboring colonias in a megastrip of roadside sprawl. Migrants pour in from Central America and the mainland with high hopes but nowhere to go but down. A lot of glue gets huffed here, and when travelers are robbed or gang-stomped, the area between Camalú and Punta Baja is where it happens.

In the past, the region was a laid-back zone of year-round overcast, empty reefs, and rich brant hunting and yellowtail fish- ing. Today, San Q can seem a desperate place.

Three years ago, hundreds of laborers and their fami- lies were denied payment by their patrónes, and the looting commenced. When the military regained control they found the rabble in local markets and restaurants, gorging on raw meat and fish offal, clicking in their mountain dialects. The town has had a dark vibration ever since.

Jorge and I blow through the city with the windows up against a nimbus of insecticide and farmed-out dust. I can’t help but think of the town as some dreadful indicator of Alta California’s two-class future.

The situation improves as we drop into the Valle El Rosario, seeing the sphinx-like mountain formation that marks the central plateau. The first boojum and cardon are spotted, and suddenly we’re in the true desert. Past the buried-tire corral of Tres Enriques, we drive across the spring-fed vado fringed with blue palms at Cataviña and down still farther to the winter hunting grounds.

My companion has been weathering a teeth-gnashing divorce, and his monologue chews through nine hours of driving. If his tales weren’t salted with humor and ribald speculation on his bachelor future, they would be intolerable in their lack of topical range. Regardless, we’re both ready for some peace as he turns off the motor, perched on the dune overlooking the small bay. The engine diesels, choking up the stepped-on gas bought out of a drum at Santa Ynez.

The view into the cove is a letdown. Swimming Pool Point is pretty much gone. The sand hasn’t recovered from the hurri- cane that came aground several years ago. Fat waves drag their way to shore, shapeless and slow. An osprey spirals up an invisible thermal stalking corvina, looking vigilant and bored all at once.

Inshore, the evening glow marquees the shanties of the shark fishermen’s camp with halogen spot beams of sun, highlight- ing a white shrine on the hill above. A group of young men walk toward us, finally close enough for one to gesture and hiss, “Relax.”

We toss them a greeting. It’s a much younger crew than I remember, streetwise and urban looking. A cold-eyed young man in a bandana scratches invisible insect bites. He’s muscled and lean. “No,” I answer to the tall one, “we don’t want to buy any abalone or weed. Enjoy the evening.”

While fishermen would normally show a healthy curiosity where rig and gear are concerned, this lot makes an obvious effort to avert their eyes. They stride back to their camp.

As we erect our tent, we hear a vehicle coming over the rise. Headlamps sweep the dunes, and the truck rumbles to halt 10 yards away. Jorge stares at the dusty Land Cruiser with its stack of boards, aghast. His cursing echoes across the landscape. Livid, he mumbles to himself as he assembles the fold-out kitchen. “Forty miles of coast without a soul. Forty miles. Give me a goddamn break.” After a tequila, his outrage cools to amusement.

The fellow surfers keep to themselves, busily off-loading their truck. The next morning’s quiet is broken by the two-stroke whine of the shark pangas, off to the Cedros channel. Our new neighbors, having changed the flat they hobbled in with, are loading a day kit for an assault on the next point up. They drive off, leaving their tents and camp stove.

We while away the day with sessions in the limp surf inter- spersed with reading and investigations of the dunes. A coyote trots by with a crab in her teeth, a string of drool yoyo-ing from her chin.

A few hours later, Jorge treads back to our tent after a hike. “You’re going to want to see this.” We walk to the north side of the headland. I take the binoculars and glass the beach until I find them. The Land Cruiser is buried to the pumpkin in a drift of talcum sand up at the next point. Their stick figures work silently with shovels. A half hour later, the truck rolls free. To return they must traverse a mile of wet beach with a rapidly encroaching tide. They seem to know they’re in trouble, accelerating toward us across the flats. A small point of rocks blocks their approach. Through the twin circles of the binos I see the truck fall into a hole, its snout buried under an explosion of saltwater, loose gear and parts blowing into the sky. We hoot and dance in the dunes.

The driver crawls the rig up the sand, the vehicle coming to a rest. The rocks have blown out the sidewalls of the two left tires. The engine is swamped. Bands of whitewater move incrementally closer with each set. Not wishing to stack stupidity on stupidity by risking our truck, we watch. Un milagro. A small army of fishermen walks toward them from the shark camp. They push the truck to safety en masse, and the beast sputters to life.

That evening we offer them a sundown drink, playing dumb, regaling in their version before letting on that we’d watched the whole thing.

We make time to explore the shark camp the following morning. I notice graffiti sprayed on the plywood walls of one shack. “Punta Mu.” The name is unknown to me, and I’ve been coming here for 25 years. I ask the first fisherman I see about the name. He lifts his chin to the point out front and to the adjacent points as well. “Punta Mu, Punta Mu…todos Mu.”

In the space between two shacks, Jorge sees a cross and asks the fisherman of its significance. He explains that a drunken man fell asleep with a space heater on. It ignited, burning him alive before anyone could help.

We climb the hill to the shrine and peer inside. For the most part it’s standard issue. A framed print of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Some candles. Mounted on the block wall, though, is something extraordinary: a borrego with an extra set of horns sprouting from its forehead. No obvious forensic clues as to whether it is assemblage or aberration. We chalk it up to genetics and head back to pack our gear and clean the site.

On the road out we investigate False Point. The sand is perfect and west lines spin off, their lips Saran-thin and speckled with darting baitfish. As we continue the drive, it’s apparent that every spot save the accursed Mu is rifling.

Dropping into the lee of the next point, we see it. Stark against the hardpan, flags snapping in the afternoon wind, a dusty bluebigtopissilhouettedagainsttheglare.“CircoAndreau,”the truck reads. The tent is staked to the ground with car axles, their hubs still attached. It out-Fellini’s Federico himself. Driving through the adjacent fish camp we slow to interview a passing man about the circus. “It tours the camps,” he tells us. “No matter how small. One man and his wife. He erects the tent and serves as ringmaster. She vends the tickets and is the clown.”

He asks where we have come from. I mention the mapped name of the point. “Oh,” he says. “Muy malo. Mucha chiva. Muchos adictos. They are sharkers. They trade the fish for heroin to their ice truck driver from Ensenada. They fish all day and do chiva all night. Muy malo. Did you see the cross? That is where they boarded in one of their own and burnt him alive. Muy peligroso, ese lugar.”

I ask him of the word itself.

“Mu? Es Mu y nada más. Mu.” He forks his fingers behind his head and bugs his eyes. “Contrario a los dios. Mu. Against the gods, my friend.”

The man’s little boy is standing on our running board, smiling and sucking on the candy I bring as baksheesh for such occasions. As his father walks away, he stays on the truck as we troll toward the main road. I ask if he has seen the circus.

“Three times,” he says, grinning.

“What do they have at the circo?” I ask. “Tigres? Leones? What class of animals?”

“No tigres. No leones. Two dogs only.” He jumps from the running board. I see him in the rearview mirror, chasing after us. Jorge slows down.

“Solo dos perros,” he screams in our dust. “Dos perros sola- mente.” He’s laughing as he turns on his heel, marching back to the camp.