“People definitely felt the film was too hot to handle. They were scared of it.”

Over the course of the next few months, the beautifully crafted documentary The Life and Death of Westerly Windina will be showing at a handful of film festivals while its producers work out a way to get the film in front of a larger audience.

The rough back story you know.

In the late sixties and through the seventies Queensland surfer Peter Drouyn was one of the hottest in the biz. And when he wasn’t giving hell in the water he was busy putting his wildly creative brain to work. He invented man-on-man surfing, which continues to this day, introduced surfing to China, became a lawyer, owned a fleet of surf stores, ran a drama school, and, at age fifty four, slipped out of his masculine shell to reappear as head-turning show-girl Westerly Windina.

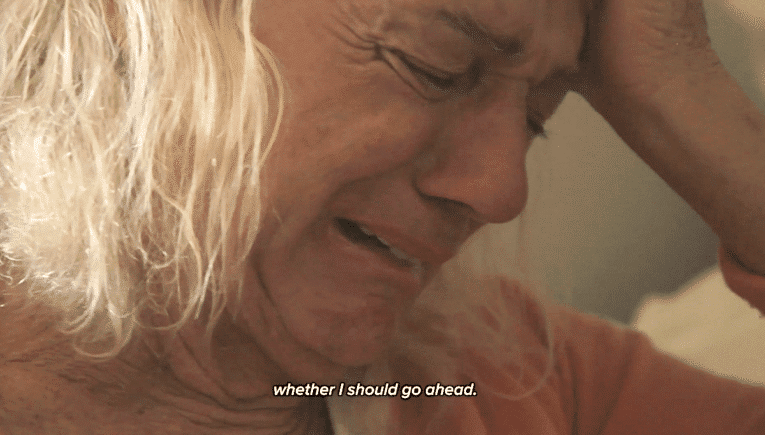

Ten years later, and followed by directors Alan White and Jamie Brisick – Briz wrote a book about Drouyn called Becoming Westerly, buy here, you should, etc – flew to Thailand for gender reassignment surgery.

A happy ending of sorts, you’d think, but Drouyn was never afraid of doin’ the old switcharoo and, hence, The Life…and Death…of Westerly Windina.

Earlier today, I gave Alan White, whose 1999 film Erskinville Kings launched the careers of Hugh Jackman and Joel Edgerton, a call to discuss The Life and Death of Westerly Windina.

First, you gotta congratulate the director, who is sixty-four but looks oh so many moons younger, like a haggard thirty-nine-year-old nightclub habitué maybe, on what he calls “an epic journey” but you gotta also, say, a dozen years, brother, what took you so long?

Ol Al laughs and says,

“If you’d gone back to 2011 when Jamie and I are about to jump on the plane to come over and interview Peter for the first time, we thought the project would be complete within eighteen months, two years tops. It was a super interesting story and one worth telling. There’s really only one Peter Drouyn and only one Westerly Windina. And it was right at the beginning of the Caitlin Jenner transgender sports movement and the Peter Drouyn story needed to be out there. His transition was such a unique journey that we strongly felt we needed to chase it. We’ve really ridden the rollercoaster of the whole transgender zeitgeist for good or bad.”

Alan points out that two of the executive producers were transgender, which was real important for one pivotal part of the film, like, the ending, which we’ll hit a little later.

“We got a surprising pushback to the film, people definitely thought it was too hot to handle, they were scared of it. It was really surprising. We thought, is this another one of Peter Drouyn’s stories that is hobbled or lost or doesn’t get the attention it truly deserves? Because Peter’s a visionary thinker. He’s such an unusual human being, the way his creative mind works. He’s written multiple screenplays. The guy doesn’t stop trying to find ways to express himself.”

It’s right now in the interview, and at this point I haven’t seen it although I will shortly after, that I note that Alan only talks about Peter Drouyn and not Westerly Windina.

That’s one hell of a plot spoiler, I say.

Surf hunk to showgirl and back again.

“It is and…look…I prefer people to see the film and to see where Peter and Westerly are now. Peter was never put to bed and Westerly was never put to bed. They’ve coexisted as an idea over that period of time and the film supplies the answers to that. You have to see it to contextualise the movie.”

And, yeah, the ending. Westerly transitions back into Peter.

But, says Alan, there was pressure to end the film at the Hall of Fame awards sequence where Drouyn accepts his award as Westerly and where he’s all dolled up to look like Marilyn Monroe.

Detransitioning, for the progressives, has got a stigma around it, y’see. A bit of a whiff of the right-wing crowd. Only fairy tales allowed in the happy world of rainbows.

But the exec producers, by virtue of being trans, and aware that what makes a good story is truth telling, got it through.

“A lot of people originally said that this was a desperate cry for attention,” says Alan. “But there is absolutely no way on earth you’d ever go through what Peter went through. That transgender transition is like psychic upheaval on a major scale. It takes courage and commitment.”

Peter Drouyn, who is seventy-five now, still lives in a crummy lil joint in Labrador, a down-at-heel adjunct to the northern end of the Gold Coast with his thirty-something son Zachary, the fruit of his one marriage