Nicolas Cage can’t save a film that’s too busy mimicking Wake in Fright to find its own pulse.

Lorcan Finnegan’s The Surfer doesn’t just tip its hat to Wake in Fright—it raids the 1971 Australian masterpiece’s wardrobe, steals its car, and drives it off a cliff.

This Nicolas Cage-led thriller, slathered in sunscreen and psychosis, is a shameless knockoff of Ted Kotcheff’s iconic descent into outback hell, swapping kangaroos for surfboards but forgetting the soul.

For 99 minutes, we’re stuck watching Cage unravel in a facsimile that’s less homage than high-budget karaoke.

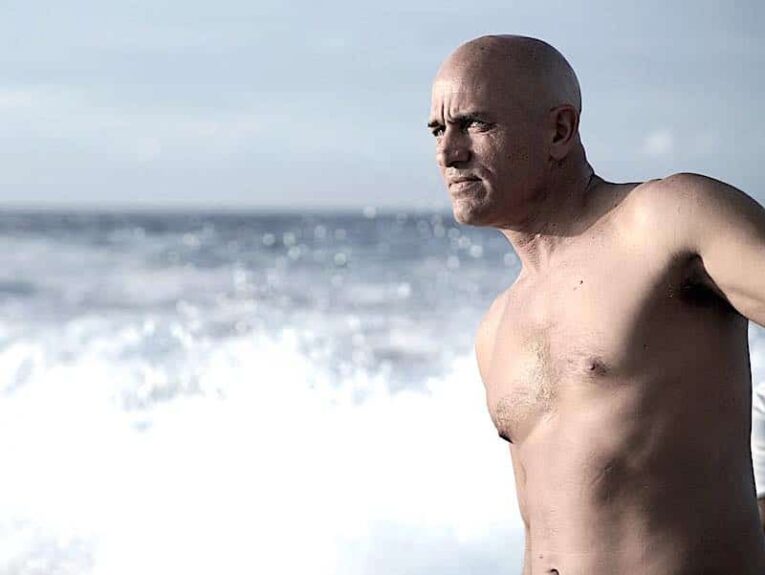

Cage plays The Surfer—no name, because why bother?—a washed-up Californian returning to Luna Bay, an Aussie beach where he surfed as a kid before life dealt him a bad hand. He’s there to buy his old home and reconnect with his blank-slate son (Finn Little, barely a blip).

If this sounds like Wake in Fright’s John Grant, it’s because it is: same outsider, same hostile locals, same spiral into primal madness. The surf bros, led by surf poncho-wearing Scally (Julian McMahon, all teeth and no menace), enforce a “Don’t live here, don’t surf here” rule straight out of Wake’s insular playbook.

What follows is a beat-for-beat rehash—humiliation, dehydration, lizard hallucinations—until The Surfer’s living out of a car, slurping puddles, and screaming “Eat the rat!” in a scene that’s pure Cage but no Donald Pleasence.

Why does this sting? Because Wake in Fright is a cinematic titan, one of the greatest films ever made, and The Surfer’s pilfering only highlights its own shortcomings.

Kotcheff’s film, adapted from Kenneth Cook’s novel, is a visceral gut-punch: John Grant, a schoolteacher trapped in a remote Outback town, is stripped of his civility by booze, gambling, and the predatory masculinity of the locals.

It’s a masterclass in tone, balancing gritty realism with surreal horror. Every frame drips with menace—dust-choked visuals, Pleasence’s unhinged doctor, the infamous kangaroo hunt—all building to a portrait of alienation so universal it’s been called the Australian Heart of Darkness. Its rediscovery in 2009 cemented its status as a cornerstone of the Australian New Wave, a film that doesn’t just depict a man’s collapse but makes you feel the existential rot. It’s iconic because it’s fearless, peeling back the veneer of civilization to expose something primal and true.

The Surfer, by contrast, is a pale Xerox. Thomas Martin’s script wants Wake’s depth but settles for vibes. Finnegan apes the psychedelic flourishes—lizard zooms, Cage’s bloodshot eyes, but misses the moral weight.

Where Wake’s locals are complex monsters, Scally’s crew are cartoon bullies. Where Wake builds dread with precision, The Surfer drags, repeating Cage’s misery until it’s numbing. The climax, a half-cocked nod to The Swimmer via Wake’s nihilism, flops like a beached fish. Radek Ładczuk’s cinematography, all searing whites and feverish reds, is the one nod to Wake’s oppressive aesthetic that works, but it’s not enough.

Cage, however, is a one-man cyclone, howling and sobbing with enough gusto to fuel a dozen B-movies. His rat-chomping frenzy is a GIF waiting to happen.

But even he can’t save a film that’s too busy mimicking Wake in Fright to find its own pulse. McMahon’s villain is a paper tiger, the social commentary (class? toxic masculinity?) is cribbed and muddled, and the pacing sags like wet sand.

The Surfer isn’t just a rip-off—it’s a reminder of why Wake in Fright endures as a colossus of cinema, its raw power untouchable.

Cage completists might stomach the ride, but the rest of us should dust off Kotcheff’s classic and leave this soggy imitation to dry out. ★★ (out of ★★★★)