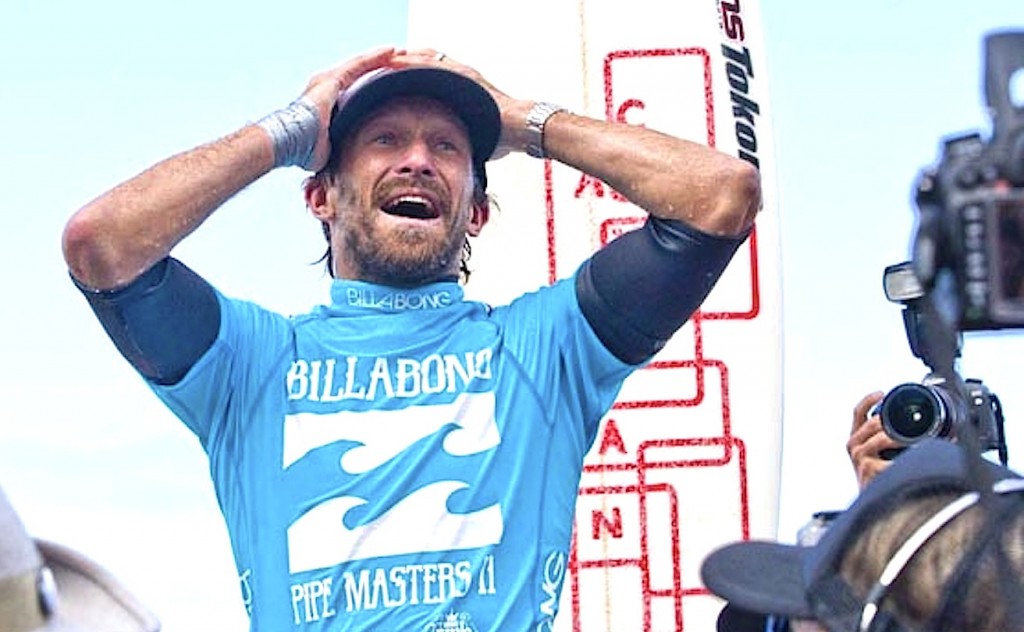

Feeling tired after that paddle out? You ain't even close to being cooked says new study…

Let’s get one thing straight. BeachGrit isn’t of the belief that going to the gym can make you a better surfer. You think John John and Dane lift and squat and shake ropes to make their turns sharper and their oops’ higher?

But what about… fatigue? That’s different to strength. It eats me alive, probably does you too. After a couple of consecutive waves, after a difficult paddle-out, we’re off our game. We squeeze in two turns instead of four, we fall off in the shorey.

And therefore should we train?

According to a new study about fatigue, it turns out we’ve got a ton of gas left in the tank, even after that paddle out, even after catching four waves in a row.

And that whole thing about lactic acid? The juice actually… helps.

The New Yorker reports, “The study, which was published last month in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, by Samuele Marcora, who heads the University of Kent’s Endurance Research Group, and two of his colleagues at Bangor, Anthony Blanchfield and James Hardy, is the latest salvo in an ongoing debate about the very nature of fatigue. According to one study fatigue is ‘the inability of the contracting muscles to maintain the desired force.’ But what causes it? Physiologists in the early twentieth century studied exhaustion by cutting off the hind legs of frogs and electrically stimulating the muscles over and over until they couldn’t contract anymore. In 1907, the Nobel Laureate Frederick Hopkins and one of his colleagues showed that the depleted frog muscles were bathed in lactic acid. Their experiment gave rise to an enduring—and incorrect—explanation for muscle failure; scientists now know that lactate, the form in which lactic acid occurs in the body, actually fuels muscular contraction rather than inhibiting it. Nevertheless, the view of fatigue as a mechanical breakdown has persisted. You max out your ability to pump oxygen, the acidity of your blood creeps up, and the neuromuscular signalling between your brain and your muscles gets weaker: one way or another, you hit a limit.

“Marcora believes that this limit is probably never truly reached—that fatigue is simply a balance between effort and motivation, and that the decision to stop is a conscious choice rather than a mechanical failure. This, he says, is why factors that alter a person’s perception or motivation (monetary rewards, for example) can affect performance, even without any change in muscle capacity. In the subliminal experiments, the cyclists’ heart rates and lactate levels rose at the same rate no matter which faces they saw, indicating that nothing had changed from the neck down. Considerations like heat, hydration, and muscle conditioning, Marcora says, ‘are not unreal things, but their effect is mediated by perception of effort.’

“In other words, they don’t force you to slow down, as happens with the failing frog muscles in the petri dish; they cause you to want to slow down — a semantic difference, perhaps, but a significant one when it comes to testing the outer margins of human capability. Marcora calls his theory the ‘psychobiological model.'”

What’s it all mean for you and me? That you’ve got a ton in the tank. Those eight-hour surfs and open-ocean reef paddle-outs (think Teahupoo) you think are beyond you? They ain’t.

Read the rest of the New Yorker story here. (Just click!)