Your favourite surf writer reports on Californian slaughter in The New Yorker…

Back in December, Chas Smith and I were swinging our bag around LA, chasing advertisers, web developers, and a few other things, although, as always, observing a scrupulous, if cruel, chastity.

As we pulled into a mall carpark for a lunch meet (why the malls? Always malls!), Chas called:

“Turn on your radio. Mass shooting a few miles away.”

Big deal. Every day in the US, right?

At least it didn’t have an Islamic component, I thought. The last thing the USA needed was violent religious zealotry, especially of the sort giving London, Paris, Amsterdam and, lately, Sydney, its rich multicultural favour.

But, yeah, as it turned out etc.

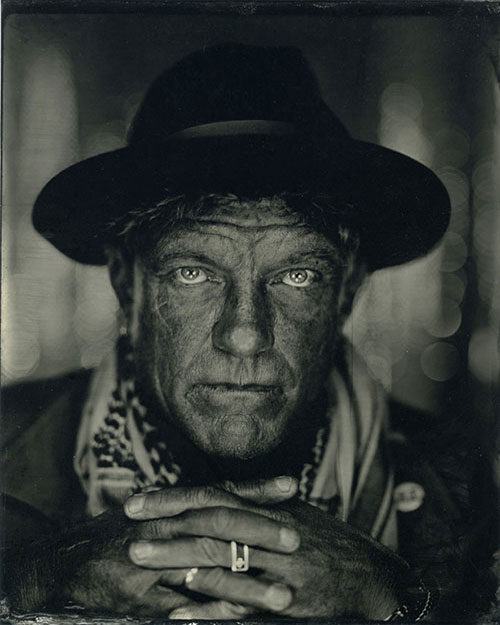

In this week’s New Yorker magazine (February 22 issue), your favourite heavyweight surf writer, Bill Finnegan, pieces together the last days of the Pakistani-born Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife Tashfeen Malik.

You know the story of the San Bernardino Massacre? Fourteen killed, 22 knocked around bad.

Read here to fill in the gaps.

As you’d expect, Finnegan’s story is compelling. Let’s examine several passages.

“Why did the attack happen? Farook and Malik did not make a martyr video or leave a manifesto. They didn’t wear suicide vests or scream “Allahu akbar” when they opened fire. Malik did post to Facebook a short, garbled, last-minute shout-out to the leader of the Islamic State. But their families, neighbors, former classmates—and, in Farook’s case, colleagues and fellow-worshippers—expressed only astonishment after the attack. There had been no displays of anger, no indication. Only growing piety.

“Farook, born in Chicago to Pakistani immigrants, grew up in the sprawling, sunny suburbs of Riverside, just southwest of San Bernardino. Malik, born in Pakistan, had been raised largely in Saudi Arabia, where her father was an engineer. She earned a degree in pharmacology in Pakistan in 2012, met Farook on a matrimonial Web site called BestMuslim.com, married him, and moved to the United States in 2014. A daughter was born in May, 2015. He was twenty-eight and she twenty-nine when they died in a storm of police gunfire after a car chase.

“Then surfaced the strange tale of Enrique Marquez, Jr. In 2004, his family moved in next door to the Farooks on Tomlinson Avenue, in Riverside. Marquez was fourteen, lonely, struggling. He started hanging out with Farook, who was eighteen, tall and shy, and worked on cars in his driveway. Marquez became the older boy’s acolyte. Neither of them seems to have had other friends. Farook taught Marquez motor mechanics, and introduced him to Islam. In 2007, at sixteen, Marquez converted. Farook prayed with him. Soon after, he turned him on to the sermons of Anwar al-Awlaki, the American-born imam who had joined Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Together, they read Inspire, the Al Qaeda magazine, and other jihadist literature online. Farook confided that he was considering going to Yemen to join Al Qaeda.

“Awlaki was, to a certain cast of mind, a mesmerizing preacher. This world is but a station, he proclaimed. It is the next station, the Hereafter, that matters. “We do not belong here. We are travelling. . . . We need to prepare for death.” Awlaki called for jihadists in the West to attack soft targets, particularly in the United States, and many took inspiration from him, including the London Tube and bus bombers (2005); Major Nidal Malik Hasan, the Army psychiatrist, who killed thirteen and wounded dozens at Fort Hood, Texas (2009); Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the airline underwear bomber (2009); Faisal Shahzad, the Times Square van bomber (2010); and the Tsarnaev brothers, who carried out the Boston Marathon bombing (2013). An American drone strike killed Awlaki in Yemen in 2011, but his message continues to resonate through the Internet. A recent issue of Inspire reprints his work, again stressing that it is best for the believer “to perform his duty of Jihad in the West.”

“According to Marquez, he and Farook came up with two maximum-carnage plans in 2011. One was to throw pipe bombs into a crowded cafeteria at Riverside City College, where each of them had studied at different times. The cafeteria had a second-floor balcony. They could attack from above and then escape. The other idea was to hit a local freeway, State Route 91, at rush hour. They chose a stretch of highway west of Riverside. It had hills on the south side and no exits. First, Farook would halt the eastbound traffic with pipe bombs. Then he would walk down the line of cars, shooting trapped motorists where they sat. Marquez, stationed on a hill with a sniper rifle, would pick off police officers as they arrived, and then emergency workers. Marquez, who was nineteen, bought two semiautomatic rifles. (They were concerned that Farook’s South Asian looks might arouse suspicion.) Farook reimbursed Marquez. Marquez also bought smokeless powder for the pipe bombs, and Farook bought two handguns. All legal. They started practicing at local shooting ranges

“It felt cool, I’m guessing, to have this bloody-minded project. Things looked peaceful, normal, banal. Nobody suspected what was coming. Divine vengeance. Their little corner of Riverside—ranch houses, pickup trucks, the Sonic (“America’s Drive-in”) at the corner, the Macy’s and Cheesecake Factory down by 91, certainly those self-involved, blithely sinful college students, with all their partying—had no clue. The two young warriors would smite the necks of the infidels, as the Koran said. It would be a crushing defeat for the enemies of Allah. Farook had become extremely devout. He went to mosque before dawn every day, and again every night, for last prayers. Marquez was more easygoing. He couldn’t match his friend’s level of zeal.

“Then Marquez got cold feet. In November, 2012, a federal terrorism bust went down in Chino, only twenty miles away. Four men were arrested. One was from Riverside. The men had met at a mosque in Pomona. Their plan, allegedly, was to travel to Afghanistan to join the Taliban and, eventually, Al Qaeda, to kill American soldiers. The ringleader was an Afghan who had served in the U.S. military. He had used Awlaki videos to help recruit the others, who included a Mexican immigrant and a Filipino immigrant. (The group also included a confidential informant for the F.B.I.) Two of the suspects quickly began coöperating with prosecutors, hoping for lighter sentences. The other two were looking at twenty-five years, possibly more. Somehow this news slapped Marquez awake. He saw his own future, best case. He backed out of the massacre plans with Farook. They stopped hanging out.”