What happens when your sleepy lil town becomes a global hotspot for Great White attacks?

The day before Tadashi Nakahara was killed by a shark, I was surfing at the same location. It was late afternoon, the waves were small and the wind onshore.

Suddenly, I saw a school of large fish in the face of a wave. I pushed through the wave and sat up on my board, marvelling at what I had just seen. They were good-sized fish. I sat there for a little while and then it occurred to me that something might have been chasing them.

So, I turned to go in, but it was too shallow to paddle across the reef, so I started paddling around the reef to where I could access the beach. Then I noticed some turbulence about four metres in front of me. I paddled straight to shore and exited the water about five metres from where Tadashi died the next day.

A couple of months after the attack, I made an appointment with Ballina Council to ask what I should do after seeing a shark. Three times I had sat in my car wondering how long I should hang around in case anyone arrived ready to paddle out where a shark had just been seen.

I was told that electronic notice boards were being considered, even though Council was not actually responsible for what happens in the ocean. I don’t know what happened to that idea, but two years after the meeting, we still don’t have a reliable system in place.

Then Matthew Lee was attacked at Lighthouse Beach. I was surfing with a couple of guys at the north end when one of them paddled over to me saying that it looked like something was happening at the other end of the beach. I had heard a siren, but figured it was headed somewhere else, since everyone at the lookout was just staring out to sea like normal. They had obviously not noticed the commotion at the other end of the beach.

I ran down the beach to see what had happened, but was told tersely to go away. I can’t blame them for being blunt. They were dealing with a horrific injury. I guess I was only trying to digest what was happening. But, nobody had called us out of the water and a few guys were still surfing further north.

Ironically, news of the attack spread rapidly around the world. Journalists descended on Ballina and the mayor had to deal with what seemed like a real-life episode of Jaws. I already knew that bureaucracy was preoccupied with its own preservation. So, I set up a Facebook page called Ballina Shark Reports, which grew rapidly to 6,000 likes, half of them from the local area. Our local parliamentarian mentioned the page in state parliament, suggesting it was an indication of concern felt by the community. But the service itself was not supported by the government, despite numerous attempts by me to get the various authorities involved.

After five weeks and 35 shark reports, I deactivated the page because I was not sure if the service could be relied upon throughout the longer days of summer. Even with a few committed volunteers, it was difficult to monitor every daylight hour. Some people thought the page was bad for tourism. So I was also afraid I might be blamed if any businesses happened to fail, as they often do in a small town anyway. I was disappointed because I knew how much people valued the service. Within minutes of a report coming in, I could see the post being shared across the community. I don’t know how many of these people were surfers, but the number of middle-aged women using the page suggested that a lot of mothers were worried about their sons spending time in the ocean.

I gradually got back into surfing and tried to avoid the topic, especially on my way to the beach. But, you would feel sick every time you heard an ambulance. Then, Sam Morgan was attacked while surfing at Lighthouse Beach – the third attack that year, all within a kilometre of the rivermouth.

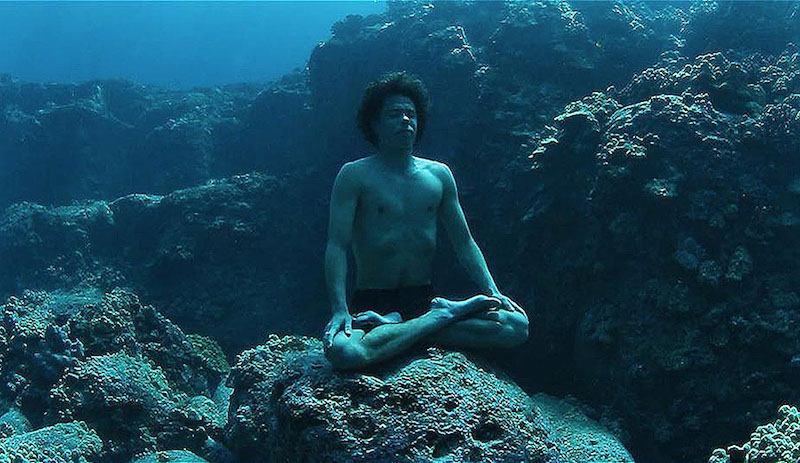

It was really difficult to keep surfing after so many attacks, but there were so many waves going unridden. People also tended to surf in groups, so even if it got semi-crowded at one location, the next beach was usually empty. You would feel courageous just paddling to the next peak. Another bonus was the abundant sea life. One day, a whale ploughed through a set as we duck-dived right beside it. Sometimes you get a fright when a dolphin suddenly pops up next to you or a stingray glides underneath. It is awesome to feel connected with nature. But I don’t like being part of the food chain.

Then Cooper Allen was attacked. I was standing in waist deep water, about five metres away, when I saw a shark in the face of a wave between me and three guys sitting further out. A few seconds later, I heard a shout, followed by the nose of a board sailing through the air. I thought the board had been snapped in half, but the back end was just hidden behind the wave.

As I paddled toward Cooper, I saw his mates, Tom and Jae paddle toward him. It makes me smile every time I think about that moment. Two young guys trying to protect their mate. How many times must that have happened in human history?

I jumped over the wave and looked over to where the attack happened, half expecting to see a dismembered body. What I saw was Cooper swimming backwards, away from the shark, which I then realised had swum away with the tail of the board in its mouth. The shark stopped about five metres from Cooper and was thrashing with the board still in its mouth, shuddering vertically in the water. As I paddled toward Cooper, I saw his mates, Tom and Jae paddle toward him. It makes me smile every time I think about that moment. Two young guys trying to protect their mate. How many times must that have happened in human history?

Once again, the media circus begins and as I see Tom and Jae being devoured by Channel Seven, I realise that I have to speak for them. When interviewed by The Australian, I made my position clear. I honestly couldn’t care less if these creatures went extinct. Just because they play a role in the ecosystem doesn’t mean that role can’t be played by other species of shark. At least two peer-reviewed academic papers make that case.

But the scientific community is too beholden to environmental ideals to share that information with the public, even when asked to make submissions to a Senate Inquiry debating the matter.

In my submission, I propose that the government withdraw from the debate by allowing interested parties to bid on the fate of dangerous sharks. If people want to protect sharks, they should demonstrate their commitment by spending their own money and not relying on taxpayers. Likewise, if surfers want to enjoy the ocean without the risk of shark attack, they should also pay up. Both sides of the debate should put their money where their mouth is. I can’t see any other way of settling the dispute.

Either you value humans or you value sharks. The middleground is an illusion.

The first hearing was held in Sydney, where a cancellation gave me the opportunity to address the committee. The mood was respectable, if a little self-congratulatory, with headstrong environmentalists speaking for the planet. I knew I was speaking for a section of the community, many of whom were reluctant to voice their concerns, for fear of copping abuse for not wanting to sacrifice their children to Gaia.

So, I focused on the issue of protecting children from predators.

It is a simple idea, but also symbolic of how we have lost our way as a culture. I am hoping that the silent majority teaches the Greens a lesson, because I think they have made a serious blunder on this issue.

It is a perfect example of why society must not give in to vocal minorities.

(Editor’s note: this story first appeared on Dan’s fabulous blog. Click here.)