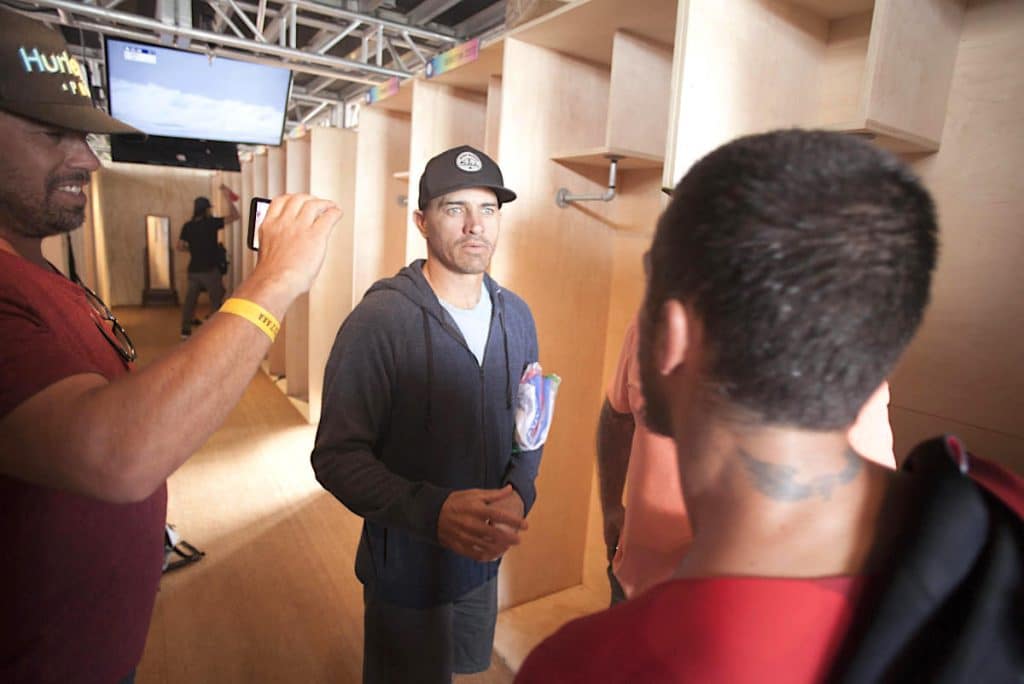

Is the 11-timer a tragic hero, ageing gracelessly, losing his grip on both power and reality? And will Pipe provide a happy end to the Slater psychodrama?

At the risk of kicking a dead horse, or a moribund GOAT, let us turn our thoughts once more to the ever-fascinating case of Robert Kelly Slater.

Yesterday, during a four-hour round trip to the surf, I finally brought myself to listen to Slater on Joe Rogan’s podcast. They weren’t the two most riveting hours of my life but actually I didn’t think he came across too badly, and certainly not as some kind of irredeemable bell-end.

Oh, I’m not saying he isn’t prone to narcissism, or that he doesn’t deserve the criticism. I do not mean to defend Kelly Slater, as such, but to defend the idea of Kelly Slater.

The world needs heroes.

It also needs villains.

But heroes and villains are crude archetypes, the stuff of children’s stories. There’s not necessarily anything wrong with children’s stories in themselves, not even when read by adults. They can be edifying and life-affirming and all the rest of it. But to go no further would be to deny life’s depth and complexity, and to deprive ourselves of so many of its joys.

How much more fun, how much more interesting, how much more conducive to online speculation and shit-talking, to have characters who do not fit neatly into either category; characters who resort to villainous means in their pursuit of heroism, or attain heroic status in their very villainy.

JP Currie wrote last week that there is a time when even our deities should “slip away with dignity to burn brighter in our memories with every passing year”.

He is right, of course. A man should know when to leave the party.

But as anyone who has ever had one too many drinks will appreciate, knowing when to leave the party is far more difficult than it sounds. “What harm could one more drink do?” you tell yourself. Or, “Who knows, I might still pull.”

And the party is, after all, where the party’s at. Home is so boring by comparison.

Speaking of leaving the party, and of burning brighter in our memories with every passing year, JP’s article put me in mind of the trajectory of another sporting great. In extra time of the 2006 World Cup final, the game he’d already announced would be his last, Zinedine Zidane head-butted a member of the opposing team in an off-the-ball incident, and was duly sent off. The other player had whispered something in his ear, and Zidane flipped. It cost France the final. It was unthinkably stupid.

Shortly afterwards, the novelist Javier Marías wrote a column for one of the Spanish dailies, arguing that, thanks to the headbutt, the story of Zidane’s career had been elevated to the status of great literature, and would linger far longer in the collective imagination.

“Yes, in a sense it’s a shame what happened,” wrote Marías, “but in another sense you have to thank the great Zidane, who in his final hour has left us a story that’s profound and strange, whose surface is uneven and furrowed, and not a tale so predictable and polished it cannot be reread.”

Slater has never been the violent type and his final hour has been drawn out to over a decade. And yet, while his defining gestures have lacked the cataclysmic poetry, the dramatic finality of a Zidane head-butt, they have been exquisite in their own way.

Telling Andy Irons he loved him moments before a Pipe Masters final.

Unveiling his new wave pool the day after de Souza won the world title.

The numerous minor incidents that have generated content on this website and others.

The point is that Slater, too, is a tragic hero. He is part King Lear: self-obsessed, ageing gracelessly, losing his grip on both power and reality. He is part Narcissus, even to the extent of owning his own pool – a pool in whose convex surface he can, on glassier days, see his own reflection. He is part Achilles, if only in his vulnerability to foot-related injuries.

Unlike us, he is a freak, physically and perhaps also mentally. But like us, he is flawed, and thus his is a story that keeps on giving. He isn’t perfect, but then as his own wave pool has demonstrated, perfection grows old pretty quickly.

In the late-17th and early-18th century King Lear was often altered to incorporate a more cheerful resolution for the benefit of audiences who couldn’t handle the tragedy of the original.

The Slater psychodrama has not yet reached its conclusion. Pipe is just around the corner.

One can appreciate the truth and power of tragedy while still hoping for something approaching a happy ending.