"You can't make an omelette without breaking a few Chondrichthyes."

Except where do you place yourself on the sliding Hippocratic scale? The “Do no harm” one? Let’s place Jains at one end, carefully tiptoeing around so as not to step on and thereby kill any bugs. Wearing face masks so as not to breathe any airborne organisms in thereby killing them and let’s place cattle butchers on the other end. Big burly men whacking gentle cows in the head with some giant bolt that penetrates their brains.

But where are you? Do you eat Impossible Burgers sometimes or never?

And where would you place conservationist-leaning biologists?

I think you’ll be as surprised as me to learn they are much closer to the butcher than the Jain and let’s learn all about their bloodlust for “lethal samples” in the very latest Scientific American.

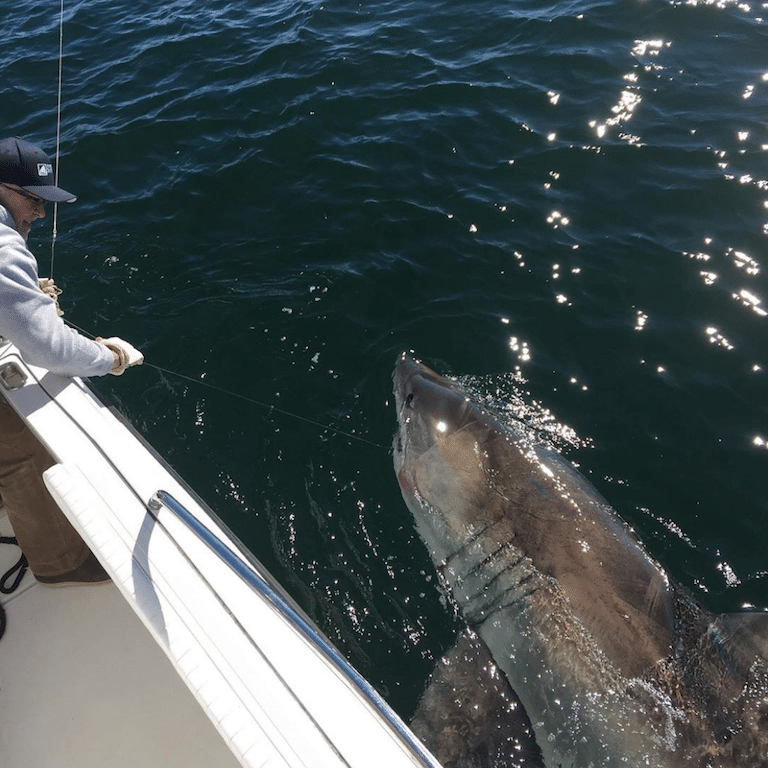

Sharks are some of the most fascinating, most misunderstood and most threatened animals in the world. Many scientists of my generation chose to study these amazing animals explicitly because they’re threatened, and because science can help; this was a major motivation for my choice to pursue a career as a marine conservation biologist, and a major influence in similar decisions by other shark researchers whom I surveyed. As we progress through our education, some of us are surprised to learn that effectively protecting entire species of sharks sometimes requires killing individual sharks—and many non-expert shark enthusiasts are outright shocked to learn this.

Every once in a while, this conflict between the goals of animal welfare and the goals of species-level conservation spill out into the world of social media, when non-expert shark enthusiasts discover that sometimes scientists work with fishermen to gather research samples from the sharks those fishermen have (legally) killed. This happened again recently, when just such a partnership was criticized on twitter by some non-experts.

The truth behind this ‘controversy’ is simple: many of the most important types of scientific data that we need to effectively monitor and conserve shark populations require lethal sampling. To quote a 2010 essay on this topic, “Although lethal sampling comes at a cost to a population, especially for threatened species, the conservation benefits from well‐designed studies provide essential data that cannot be collected currently in any other way.”

On and on the piece goes describing, in vivid detail, the barely concealed joy these scientists take in fishing endangered sharks. I’d image it is the same thrill the hunter feels when bagging one of the last remaining Javan rhino.

No?

Maybe I should re-read.

But quickly, where do sharks land on the sliding Hippocratic scale?

Closer to the butcher than killer whales?

Than king cobras?

Much to ponder.