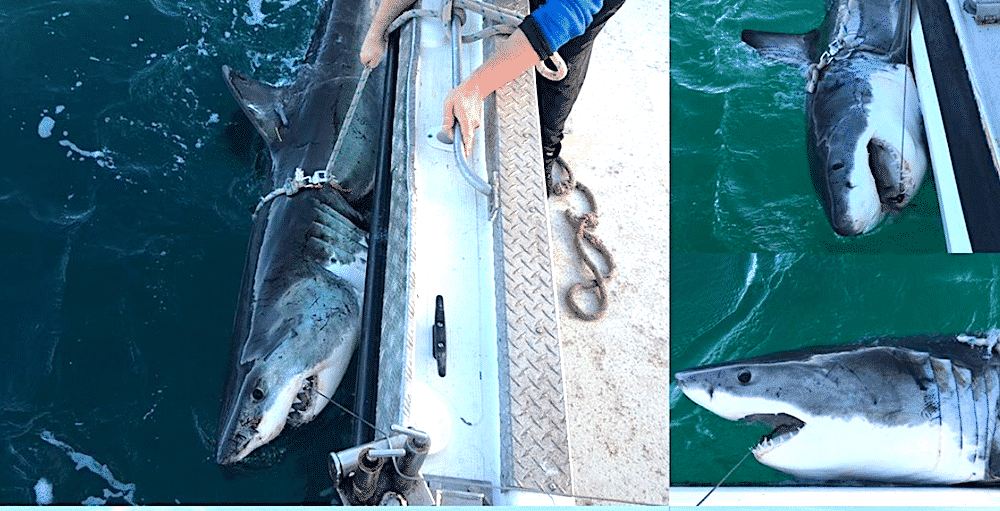

Sixteen Great Whites tagged on the drums between Evans and Lennox over three days.

We’re still distressed about young Mani’s premature demise, two weeks later, but we’re not shocked.

That kind of news puts a chill in your heart, like when I hear the westpac chopper fly past. You hope it’s not someone you know, but if it ain’t, it’s always someone who knows someone.

After reading the below-the-line comments on both my article and Dan Dobs’, as well as Dan Webber’s latest contribution my writerly soul, my surfer soul is rejoicing. They were magnificent, encompassed all points on the spectrum.

Truly, surfers, as the main targets of increasing shark attacks in Australia and globally have got control of the narrative now. Taken it back from the peckerheads and sheepish jackasses of the BBC, The New York Times, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, The Guardian, The Australian, The Wall Street Journal, Hollywood etc etc.

I asked two questions in the last article.

One, had we reached a tipping point with the latest attack and two, did the architects of the White shark recovery in (eastern) Australian waters have an ethical obligation to consider the human cost of that decision.

Smart people said no to the first question below the line and, now that the emotion has worn off, I think they are correct, even though the history of human/shark relations in Australia is replete with tipping points.

As to the second question, well no-one really had a swing at it.

I think therefore we should rephrase it by looking at some of the orthodox thinking which surrounds the vexed shark issue in light of the science and take an axe to some of the current shibboleths if recent data dictates it.

The currently accepted reason for the increasing rate of attacks in Australia (and worldwide) is the increasing number of surfers in the water. Not the sole reason but the one that does most of the heavy lifting. It was framed eloquently as a question of increasing surfer hours by one commenter.

If that were true, you would expect places of high surfer numbers to suffer more attacks. Attack facts do not support that theory. Attacks happen in areas of small surfer numbers. Mani was attacked in a small group, as was Rob Pedretti, as was Tadashi, and Matt Lee, and Craig Ison and Lee Johnson and Cooper Allan and Paul Wilcox and Sam Edwardes etc etc.

Posit two days on the Ballina coast as a thought experiment.

One is a pumping day with a very high number of surfer-hours. The other a delicate babyfood day with a low number of surfer hours.

Which has the highest risk of attack?

The data conclusively supports the theory the low surfer hours day is the more dangerous. Crowds, paradoxically, decrease the chances of attack.

Small numbers are the most dangerous days/situations.

Second shibboleth. You go in the water, you accept the risk. Very eloquently stated by Maurice Cole.

Yes, and very true.

What is forgotten is how quickly and by how much the risk has changed in this area.

Prior to September 2014’s fatal attack by white shark on swimmer Paul Wilcox the area was not known for White sharks. The last fatal attack was by bull shark on Pete Edmonds at North Wall in 2008. Prior to that, honeymooner John Ford was bitten in half in Byron Bay when he put himself between a six-metre white and his beloved in 1993.

Years separated attacks.

That all changed in 2015.

We went from isolated incidents to a hot spot where attacks and incidents happened on the reg. The actual risk is very different now.

Why?

Theories that blame increasing surfer numbers don’t make sense, as we have discussed. You could run the line that our surfer consciousness is too aggro and is an affront to the peaceable White shark as advocated by Anna Breytenbach.

But, if that seems loopy, what you are left with is an increasing number of Whites, mostly juiced-up teens and sub-adults that seem to have a kink for games of chicken with surfer legs, if you’ll pardon the anthropomorphism.

The surfer theory, as presented by George Greenough, is the White shark is in bounceback mode and the juvies and sub-adults are back to claim territory ceded from days when they were openly fished and the solution to a White shark hanging around was a chain and a 20/0 hook.

The numbers from the smart drum line program support that.

The fishing over the last week has been very good. Down at the Ballina marina in the grungy post-industrial West Ballina area I waited in the rain for the shark contractor to come in. They’d tagged four that day. One had interrupted my go-out at small fun Lennox Point.

Sixteen Great Whites tagged on the drums between Evans and Lennox over three days.

The shark contractor brought up the third shibboleth.

People think the ocean is over-fished but it’s teeming with life here, he told me. The ocean is being raped and pillaged, but it’s in rude good health on the North Coast.

Those two statements seem incompatible, but they are both true. Blue sharks and other oceanic species are being slaughtered for shark fins but White sharks are regionally/seasonally abundant and largely immune to fishing pressure.

Both those things are also true.

Latest science on the food stocks for White sharks in Aus, salmon, seals and whales all point to abundant food sources.

Dolphins make up prey for White sharks, they seem scarcer since the Whites showed up, but that is anecdotal.

The last shibboleth is the one most beloved of certain social scientists and academics. Dr Chris Neff from Sydney Uni is the most well-known spokesman.

According to this world-view the problem of increasing white shark bites is a mostly human psychological one. In a 2012 TedX talk he claimed “shark attack” was a phrase that has been invented. The holy grail and end point for this view is that “knowing more about shark behavior will reduce human–shark interactions.”

Unfortunately for this utopian view, the data sadly suggests not.

The problem appears not to be psychological or one of language or solvable by knowing more about shark behaviour. An honest re-writing of the recommendations for avoiding shark attacks would state 10am-3pm in small groups on sunny days in small-medium surf is the most dangerous combination of circumstances.

Biology does the explanatory heavy lifting: opportunistic attacks from apex ambush predators don’t give a flying fuck about human psychology.

Wrassling with these questions ain’t easy and I don’t want anyone walking away from this thinking I’ve got answers.

I have a different view to Dan Webber on the smart drum-lines. I think that might be the best compromise we’ve got at the moment.

It roughs up the teenage Whites before they get too comfortable and gives them a little free boat trip from the area courtesy of the taxpayer. The data from that is useful to me. If the fishing is good and Whites are on the sniff I’ll modify my go-outs.

I won’t stop surfing but I’m not going to paddle out in junk beachies.

Not worth losing a leg over.

Respect for the predators, yes.

But I can’t get down with the veneration.

Humans have lived, played, worked, travelled in the ocean since Year Dot.

That’s what we do.

If Whites are coming back we’ll have to find a way to co-exist and if that means juveniles need to learn a little fear and caution of these skinny limbed mammals who play in the surf zone then so be it.