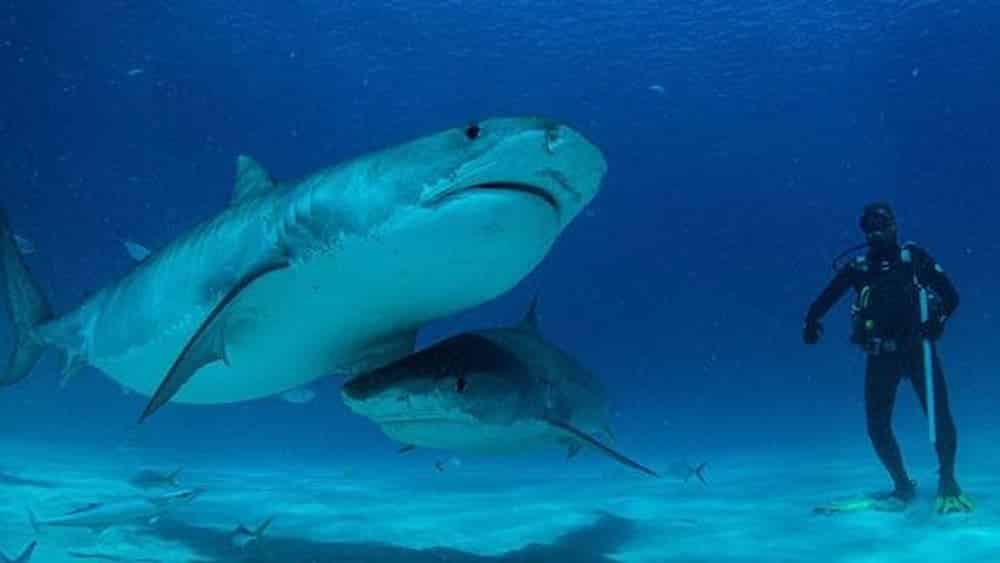

"The most brutal conclusion imaginable wrapped inside an ocean monster six metres long, weighing two tonnes, with an open mouth that is red, the colour of blood, and white, the colour of teeth."

It’s a quirk of fate that Mick Fanning, three-time world champion, will be remembered, forever, as the surfer who was almost cleaved in two, live, by a fifteen-foot White at Jeffreys Bay in 2015.

In a profile in today’s The Weekend Australian, the decorated journalist and author Trent Dalton works his lyrical alchemy, wrapping the attack around the death of two brothers, a divorce and a new documentary Fanning stars in called Save This Shark.

Five years on, Fanning tells his interlocutor that he still dreams about the hit.

The nightmare is mostly the same every time. He’s back in the water on his surfboard and he’s waiting for a wave and he knows it’s Jeffreys Bay, South Africa, where all the madness began in 2015 and if he knows where he is in the dream then he knows what’s coming. Death. A splash behind him because that’s how it happened in real life. He turns around on his board and what he sees is the end of the ride. The end of all good things. A finale to an impossibly full life of only 39 years. The most brutal conclusion imaginable wrapped inside an ocean monster six metres long, weighing two tonnes, with an open mouth that is red, the colour of blood, and white, the colour of teeth.

And then he wakes and he realises he’s still alive. Still in one piece. Same ol’ unassuming, uncomplaining, knockabout, sun-bleached Gold Coast surfing genius Mick Fanning, flat on his back and sucking deep breaths in the darkness of early morning, sweaty head full of dreaming, beating heart too full of muscle remembering.

The most brutal conclusion imaginable wrapped inside an ocean monster six metres long, weighing two tonnes, with an open mouth that is red, the colour of blood, and white, the colour of teeth.

“I mean, it’s like I’m in the actual position I was in,” Fanning says. “It’s a reality dream. You sort of learn your body can do so many things to make things real and not real and I just had to learn, ‘OK, that moment’s been done. It’s not real. These dreams are just coming back’.”

He shakes his head in the cool winter air of Coolangatta, shivers with his hands in the pockets of a black winter coat, seated at a cafe table beside the footpath of a bustling post-morning-surf dining precinct. “I still have this PTSD where, if people splash behind me, it freaks me out,” he says. He chuckles when he says this. It’s not the laugh of a man trying to put on a brave face. It’s the laugh of a man trying to make sense of the absurd; a man grappling with a trauma that he realises he avoided confronting for close to five years.

Most of The Weekend Australian’s stories are shackled by a paywall.

This ain’t.