"What has become of our culture that human life is so undervalued?"

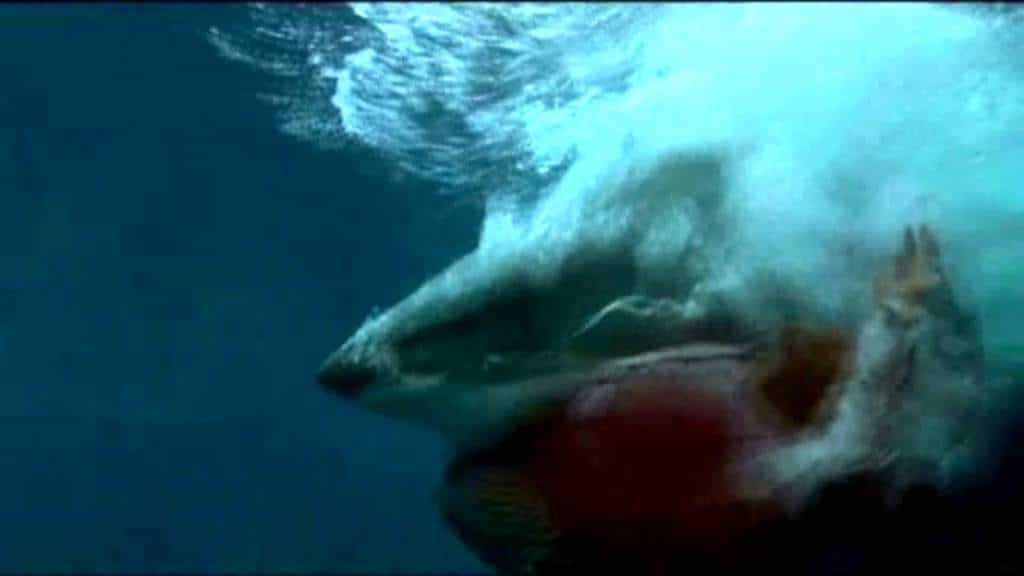

The dramatic deaths of two Aussies enjoying a refreshing swim in the summer heat is a tragic reminder of the ever-present risk of encountering a shark in the wild.

Having witnessed an attack, and been in close proximity to another, I feel sickened that these tragedies are allowed to continue. What has become of our culture that human life is so undervalued?

It’s not easy being pro-human in the shark debate currently roiling Australia. Eco-warriors think we not only hate sharks, but nature in general. Apart from being wrong, such religious zealotry probably indicates that they hate humans, and society in general. So, it is not surprising that people avoid the conversation — no doubt fearing retribution.

But, the Australian government ought not be swayed by this vocal minority.

I recently attended a public lecture by shark scientist Victor Peddemors, who works for the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI). He confessed that, while the purpose of their research is to find a solution to shark attacks, it is very difficult to identify risk factors when there are so few attacks.

For example, in research co-authored by Peddemors, El Niño was found to be a likely risk factor. However, two years later, a spate of attacks occurred during a mild La Niña.

It is foolish to expect that a solution will be found that does not involve reducing the population of sharks. That is why I have suggested targeting the most aggressive sharks with an electrified drumline that deters less aggressive sharks. It seems like a reasonable compromise. But, the government is afraid of the inevitable backlash from eco-warriors, who will continue to impose their values on society, disregarding the human cost, or outright celebrating it.

The problem with the debate is that it hinges on a false dichotomy pitting humans against nature. The anti-human sentiment has become so ingrained in progressive thought that the occasional shark attack is likely viewed as a necessary sacrifice. It is futile arguing with people who subscribe to this worldview.

But, there is hope, if we reframe the debate, so that it focuses on protecting all mammals in the wild, not just humans.

I have argued, for instance, that the added benefit of significantly reducing the rate of shark attacks is that it would set the stage for the removal of shark nets, which regrettably catch a lot of non-target species, including dolphins and whales. But, any reduction in shark attacks would apply to all potential prey, including dolphins and whales. So, the removal of aggressive sharks could have a profound effect on their welfare, too.

The only response I have received from the government has been a stock standard reply, outlining the current suite of shark mitigation measures, designed to balance the protection of sharks with the protection of people. Their letter made no reference to my proposal.

So, I requested a meeting, hoping to discuss the matter, but they didn’t reply. The reason I persist is that I don’t believe anyone in the know actually believes that lives will be saved.

For example, in research estimating the future rate of shark attacks, our most qualified shark scientists completely overlook the effect of the government’s shark mitigation programs. Of course, the numbers are buried under a mountain of obfuscation, fancifully modeled as the widespread adoption of shark shields.

But, it is clear that the base rate of shark attacks, i.e. without anyone using a Shark Shield, is projected to continue rising at the present rate, despite massive investment in other shark mitigation measures.

The government needs to ask the scientists at DPI if they actually believe the current suite of shark mitigation measures is saving lives. While it is certainly true that shark attacks are rare, the resulting trauma ripples much further through society than other tragedies. Dubbed The Jaws Effect, the horrific spectacle of shark attacks haunts ocean users, despite the risk of injury or death being less than it is for cycling. Even Dr Peddemors is reluctant to swim out too far.

(Dan Webber is the author of Surfism: the fluid foundation of consciousness.)