"Calling Monster Hole a wave is like calling Genghis Khan a general."

There is that vast, dusty attic far down in the depths of all our minds where the images are sepia-toned and the memories click by in hazy 8mm relief, the reels clacking in the background. We wouldn’t be surprised if Chaplin or Keaton suddenly tottered into the frame.

That is where this story originates, buried underneath decades of moments, slid into the corner behind a clutter of yellowing and cracked remembrances, unnoticed but for the garish title scrawled in blood-red marker on the outside of the tin:

Monster Hole.

A name crafted, successfully, to strike fear into grommets and grizzled wave sliders alike.

A name that haunted my teenage dreams, living as it did at the outer fringes of my high school surfing existence, equal parts terrifying and alluring.

For those unfamiliar with the intricacies of the central Florida surf map, the Hole is a wave.

But calling Monster Hole a wave is like calling Genghis Khan a general.

This isn’t your typical pull up to the beach break and paddle straight into the lineup like essentially every other wave in Florida.

Au contraire, mon frere.

The Hole is an open water spot that breaks 1/3 of a mile outside Sebastian Inlet, spilling its energy over underwater rocks and a sandbar formed by the tidal flow in and out of the inlet, then dissipating into deep water like an Olympic sprinter collapsing at the end of a frenetic dash toward immortality.

Accessing the break requires parking on the south side of the inlet — opposite the northside jetty and its iconic First Peak — jumping in the swirling whitewater flowing out of its mouth, and battling the currents during the 20 minute paddle through murky, shark-infested waters.

Calling these waters shark infested isn’t just tinhorn hyperbole. Sharks are so ubiquitous in the area they even have names, like the Canova Runner, a mystical 16-foot Tiger that was hooked by local fishermen several times in the 80s only to escape each time and continue patrolling the stretch between Canova Beach and Sebastian.

Big Whites are regular visitors too, routinely spotted by anglers and even tracked in real time by ocearch and others.

Yet while Tigers and Whites grab the headlines, they aren’t even the most dangerous selachimorpha stalking the inlet. That title belongs to the shockingly, aggressively, evil Bull shark, a demon that is responsible for some of the most horrific attacks on record, an osmoregulating freak that can survive in freshwater, haunts rivers as well as oceans, and is armed like an oceanic Freddie Krueger.

A recent academic journal piece put some flesh on this nightmare bone: “[W]hereas other species might have five or seven layers of replacements waiting to move into position, bull sharks have up to 50 rows of teeth. Their narrow, sharply pointed lower teeth clamp onto their prey while broad, heavily serrated uppers rip and grind and sever, delivering a bite force as strong as 5,914 newtons—pound for pound, the strongest of all sharks.”*

But wait, kind reader, that’s not all — to add quantity on top of quality, the Bull shark is the fourth most abundant shark species in U.S. Atlantic waters (trailing only the relatively domesticated Nurse, Lemon and Blacktip). Which means not only is this cross between a pelagic tiger and a gill-bearing wolverine the most likely thing to eat you, it’s also the most likely thing to be lurking beneath you.

Swirling ocean currents, terrifying deepwater paddles, and a gauntlet of man-eating ocean beasts be damned though. Because when wind and tide and swell are just right, the Hole is a reeling lefthander that is arguably the best Atlantic-side wave south of Hatteras.**

As the Florida Surf Museum site describes it, “Monster Hole is where reality and hype come together.”

Which is why one overcast morning in around 1989 my crew decided to roll the dice. We were standing on the beach by the jetty, looking over firing First and Second Peak, wondering whether to face a crowded pack of the hottest surfers on the entire east coast or ditch both peaks and wander north to Spanish House.

That’s when a big set rolled through, and tips of feathering swell far outside the jetty surf zone caught our collective eye. There was no one out there, so we had no idea how big, or small, it was. But the waves reeled off like aquatic razor blades with machine-like repetition.

As best we could tell, we were looking at the finest lefthander any of us had ever witnessed in person. This being the 80s, we didn’t know much about the wave itself. All of our information came through word of mouth, whispers of a spot only a few had dared surf, warnings of the giant sharks fishermen had hooked off the jetty or spotted while trolling for sailfish outside the inlet.

We also had no idea why it was empty at that particular moment. For all we knew, notwithstanding what our eyes seemed to tell us, the wave may have actually been shit, or there may have been a run of bait fish taking their spastic flight straight through the lineup and attracting even more sharks than usual. (Or, more likely, the photographers on site had their lenses trained on the peaks near the jetty and wouldn’t be in position to document even the most savage of snaps out at the Hole.)

But we were young, and we lived in a geographic zone reviled by surfers around the globe as less than. That reality had put a chip on our collective shoulders, an eagerness to push the limits where we could find them, a kind of quiet desperation to test ourselves against more than two-to-three-foot beachbreak windswell.

It was the same chip that in some measure invigorated the spirit of all native Floridian surfers, the one that led other (light years more accomplished) Floridians like Kelly and the Lopez’s and Hobgoods to throw themselves over ledges at Pipe and Teahupoo, and led lesser knowns like the Kuhn crew to paddle maxing Puerto.

At that precise moment in time, we had neither the resources nor the skill to take on legendary international barrel zones. But we were standing on a beach staring at what appeared to be a properly cooking Monster Hole. So we looked at each other, shrugged, and sprinted back to the cars for the short trip south over the inlet.

Waxed up and leashed, we stood together on the beach, scanning the whirlpools and boat channel, watching the lefts reel off in the distance, trying to scope out the best line to follow on the more than quarter mile paddle to the break.

My best friend Chard*** was there. A goofyfooter and apprentice carpenter who shaped and glassed his own boards (yes, even in high school), he was meticulous almost to a fault. But once a plan was set, he would charge anything that broke.

A couple years after this day at the Hole, we paddled a mysto reef together breaking a couple of hundred yards outside Roca Loca in CR. He dropped into the wave of the day (maybe the year in those parts), a giant shadowy beast that made his seven-foot step-up look like a skimboard.

Tuffed was also with us. Six foot four and a lean, muscular 220 lbs, he was the biggest and best looking in our crew, by far — he had seven inches and probably 100 lbs on me. Truth be told, he could be a complete asshole at times – he once slugged me without warning for deigning to borrow his bible at church camp without asking first.

The fact that his sucker roundhouse didn’t make me so much as flinch was probably the only reason we became friends in the first place, his being the kind that only seemed to value the ability to inflict or, equally important, endure violence. But he did have the stones to match his macho facade and paddling a sharky open water spot was just the kind of thing that would put another notch on his psychic belt.

Of course Steve was there too. You’ve heard about Steve before, my crew’s late partner in multiple crimes whose up for anything approach to surfing and life exceeded his actual skill in the water by more than a few degrees. His love for skim boarding had just about ruined his surfing style — on a wave he always looked like he was skimming across flat water at high velocity with the same “keep your balance at all costs” kind of stance.

But he was the son of an auto mechanic fisherman who had inherited his dad’s love for engines, fondness for heavy test fishing line, and blue collar grit. He had grease perpetually embedded in the lines of his hands and fingernails, had landed his fair share of big game fish, and his constant glass half full approach never diminished the truth that he was tougher than steel wool. For all I knew, he may have been on a first name basis with a few of the sharks already. He definitely seemed giddy at the prospect of our open water paddle.

After a few minutes observing the scene it became clear that any plan would be nuked the second we hit the swirling whitewater. So Chard said “fuck it,” and took off running for the surfline. The rest of us charged behind, leaping into the water with as much momentum as we could muster, paddling like banshees as we skimmed across the foam.

We spent what seemed like hours wrestling with the frenetic currents and crashing waves in the near-shore surf zone. Eventually, though, we each made it through, coming out the other side into relatively clean deep water.

That’s precisely the moment when our thoughts returned to what was swimming beneath, silently stalking us from below. I lifted my feet behind me, doing my damnedest to keep any flesh out of the water, no small effort when paddling an 18” wide toothpick.

None of us breathed a word, terrified that any sound would alert otherwise drowsy predators. We looked at each other wide-eyed, silently slipping our hands and arms in and out of the water, paddling like Iroquois stealthily sneaking their canoes past the river camp of a blood enemy.

As we grew closer to the break, the waves seemed to grow. What appeared to be head high-ish from the beach was clearly close to double that, more on certain sets.

Impatient after a long paddle, I swung and went on one of the first lumps that we reached. It was a quick drop and short ride, the wave petering out in deep water almost immediately. I turned back toward the lineup just as the rest of the set reeled through, my buddies punching through the pitching faces of solid double overhead walls.

They scrambled for the horizon while I sprint paddled back out to meet them, all thoughts of big fish and razor-sharp teeth eclipsed by the adrenaline of making it all the way out the back to be in position for the next set.

It didn’t take long. We saw the lines advancing and paddled into position. Chard and Steve took the first two, Tuffed dropped in the third.

As I paddled up and over the face of Tuffed’s wave, I caught my first glimpse of what was behind it. A ruler-edged line, feathering off to the north, bending around the Hole’s bathymetry to peak right in front of me.

I swung and took three hard strokes, glancing down the line as I did. I felt the familiar surge under my board, only this time with more urgency, more juice, like our typical Florida beach break had done steroids and emerged thick-necked and roped up.

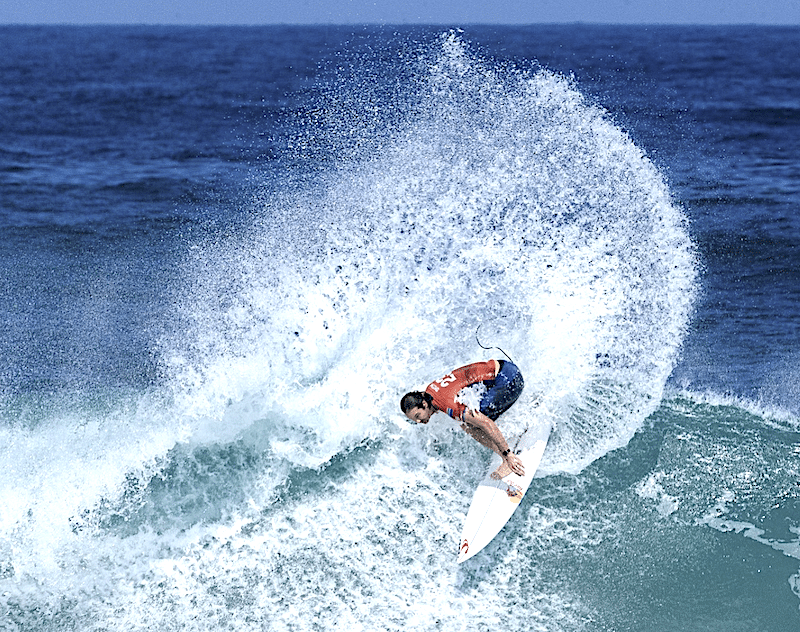

I sprang to my feet, pushing down the surge of endorphins, tucked my back knee just a little, and drew a backhand line down the face. As I approached the trough, I dug my heels into a bottom turn and headed back up, shifting my weight as I reached the lip, pulling my head and torso back around, and unloading all of the compressed speed into as critical a top turn as I had ever managed to complete.

The wind blew spray back into my eyes as I headed back down the face of the wave. I shook my head once to clear my vision and spotted Chard and Steve starting to paddle back out in the deep water at the edge of the break zone. They were grinning like toddlers on Christmas morning, all memories of the hectic paddle out wiped away.

“Monster Hole is one bad ass motherfucker,” I thought as I listened to them hooting from the channel.

Then I banked off the bending wall, leaned into another bottom turn, and headed back up toward the feathering lip, any thoughts of the return paddle to the beach stowed away, a terror for another time.

*John Gifford, The Redoubtable Bull Shark, The American Scholar (May 2, 2024).

**With apologies to Reef Road, Pumphouse, the Rocks, RC’s, and some spots we won’t discuss in the general vicinity of Jacksonville and Wilmington.

***Names have been altered to protect the living.