Daniel Russo is so close to God he can almost smell his bacon-y breath!

We are transient beings, on this earth for but a few all too short moments. And then we turn to dust. We scratch and feel immortal, at times, yet really, we are dust.

But water photography? Water photography is forever.

Photographs, unlike us, are truly immortal. They live on through the eons whether sepia-toned, black and white, color or high-definition color. They live in drawers and boxes and cell phones and computers and the internet. Aboriginal peoples on different continents often believe that photographs capture the soul. They are derided as backward. Unsophisticated. Curly headed naïve children (or straight headed in the Americas).

But they are right. Photographs capture the soul and lock it into celluloid or megabyte where it lives eternally. Captured. And how much more eternal are water photographs? That much more.

There is, first, the black arts used to bring the camera into water. Saltwater is a damaging agent. The most damaging naturally occurring agent on earth save hot lava. It rusts and corrodes. Cameras are born delicate. Small, sensitive metal pieces. Glass that can scratch and shatter. And so to keep the camera from being destroyed, on contact, by saltwater the magician must cast a spell over it. He must conjure the spirits of silicone and plastic and rubber. He must create valves.

The camera, in its housing, in the saltwater, is an aberration of an aberration. Something otherworldly. And as the magician swims out to sea with his creation and can capture souls out at sea and does capture souls he is also an aberration. A collector. And he collects souls riding waves.

And there is, second, the even more transient existence of waves. If the human life is over in the blink of an eye, the life of a wave is then over in the flutter of an eyelash. Waves, even the longest rights at Jeffreys Bay, never last long enough. And they are never repeated. Once they pass they are gone forever and no memory is good enough to hold the feeling or even really the image of a wave. Waves defy containment. They laugh at the addiction created in us. They laugh as we forever chase a feeling.

As we look at a picture of Nathan Florence, say, grinding through a perfect barrel we can put ourselves, right there. We can imagine how it feels. How racing toward the almond eye, foamball nipping at heels, tastes. The water photograph brings all of us there together. It brings us to a moment which passed, like the flutter of an eyelash, and we can live in it forever. Or until we turn to dust.

But the camera, in its housing, does contain waves and furthermore it can contain the feeling. We look at pictures and we stare at them and we sear them into our hippocampi and we remember our own experiences. Which is, third, the transportational quality of a water photograph. It takes us into our own memory, back in time, but it can also take us into someone else’s memory. I, nor most of the friends I am lucky to call my own (save the professional surfers I am lucky to call my own) have ever surfed heaving Teahupoo, or any Teahupoo for that matter, but I, and most of my dear friends, have surfed large, sucking lefts at one point or another.

And as we look at a picture of Nathan Florence, say, grinding through a perfect barrel we can put ourselves, right there. We can imagine how it feels. How racing toward the almond eye, foamball nipping at heels, tastes. The water photograph brings all of us there together. It brings us to a moment which passed, like the flutter of an eyelash, and we can live in it forever. Or until we turn to dust.

The surf shot captured from land or boat is wonderful. It is pleasant and fun and artistic. Amazing. But the surf shot captured from water is beyond all. It is, again, magic. Maybe an evil magic. Maybe something that should never be captured, but life is too short to care and, anyhow, it is not me being captured. It is not my soul. It is the professional surfer’s. The best ones doing the best things on the best waves in the best light (and proper shutter speed etc.) during the best of their youth.

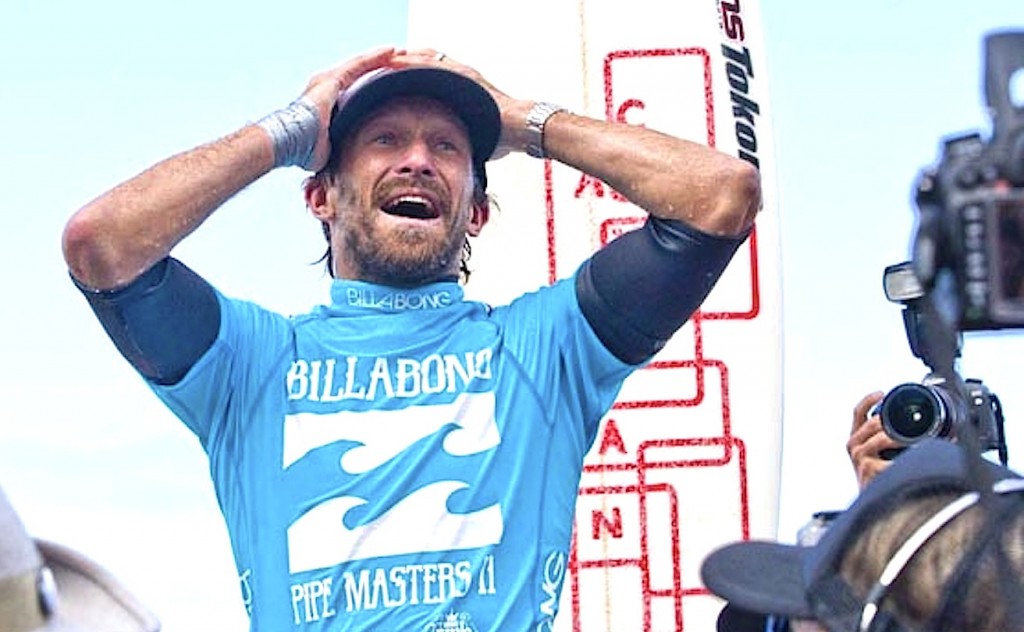

“How sad it is!” they can crow. “I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. My body will give out and I will no longer be able to send plumes of spray into the ether with strong thighs and a stronger back. But these pictures, these water photographs, will remain always young. They will never be older than the day they were taken. If only it were the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and strong, and able to frontside slob, and the picture was to grow old. For that, for that, I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!”

But in truth, they already have given their soul. They have given it to me and to my friends and to you and to every other man, woman, child who casually flips open a surf magazine, or coffee table book and gazes. And the surfer is right to despise this fact. The ugly and stupid and those who cannot even frontside hack without swinging their arms like epileptics have the best of it in this world. They can sit at their ease and gape at the play. At the surf videos. At the water photographs. They can surf Teahupoo forever as they gape. The surfer who is in the photograph, though, will grow old and he will feel the gnaw and he can crow, “How sad it is!”

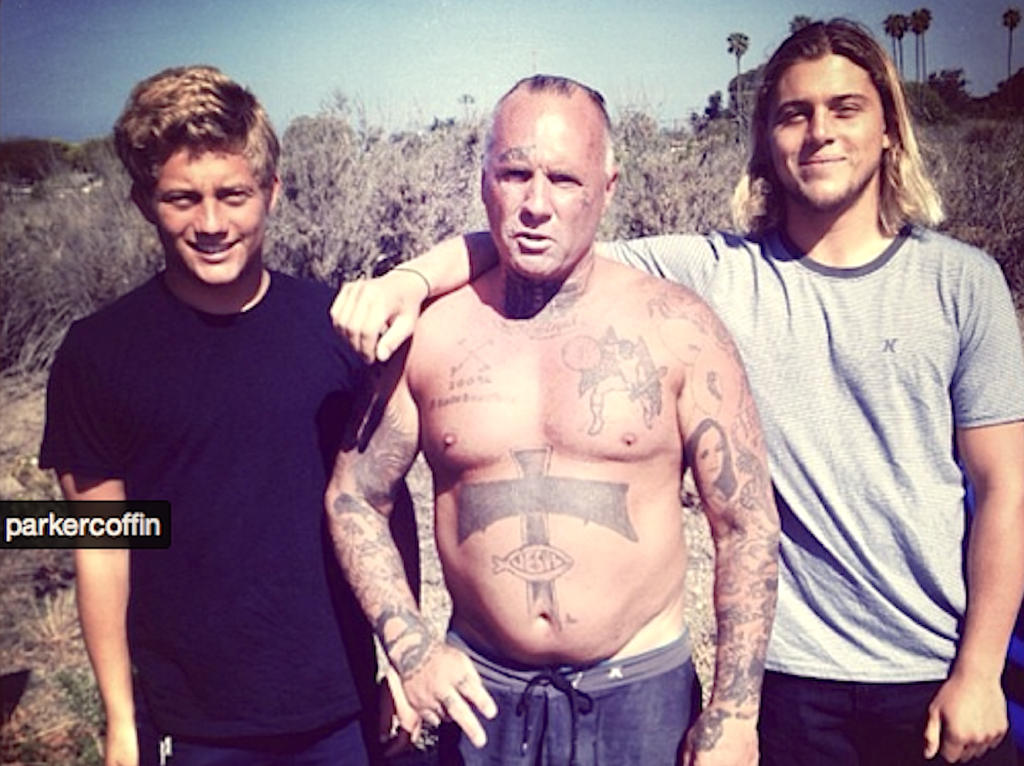

The surfer is right to despise but he should not ponder his fate for long, however. Beauty, real beauty, ends where an intellectual expression begins. So he should succumb to his fate. He is blessed and, at the same time, cursed. He should accept this and let it go and he should certainly not despise the water photographer. The magician capturing his soul in a moment of rapture. If he is mature, his unreal and selfish love could yield to some higher influence, could be transformed into some nobler passion and the image that Daniel Russo has created of him might be a guide to him through life, would be to him what holiness is to some, and conscience to others, and the fear of God to us all. There are opiates for remorse, drugs that can lull the moral sense to sleep. But here, on surf magazine page, or coffee table book, is a visible symbol of the degradation of sin. An ever-present sign of the ruin men bring upon their souls. The sin of desiring immortality and the sin of desiring one moment frozen in time.

But, and again, it is not the surfer’s fault. He is blessed and, at the same time, cursed. And not only should he not despise the water photographer, he should love him. For if Daniel Russo can give surfed-out ecstasy, a giant day at Teahupoo, a perfect barrel ridden with style and ease, to those who have lived without, if they can create a sense of beauty in people whose lives have been sordid and ugly, who cannot even slip into a backside closeout without hunching over like an ape, than they are worthy of adoration. Worthy of the adoration of the world.

I shared my theories on water photography with a famous professional surfer and with a famous professional water photographer about the capturing of the soul and the curses and the blessings and the despising. About the sin of desiring immortality and about the sordid and ugly who benefit from the images. About how beautiful those images are and about how damning they are.

The famous professional surfer looked at me, long, and he lowered his glasses (he wears glasses) and he said, “You have killed my love. You used to stir my imagination. Now you don’t even stir my curiosity. You simply produce no effect. I loved you because you were marvellous, because you had genius and intellect, because you realised the dreams of great poets and gave shape and substance to the shadows of art. You have thrown it all away with this theory. You are shallow and stupid.”

I went home to cry but found myself staring at a picture of Julian Wilson shattering the back of a wave at Keramas. The water photographer, I know not which water photographer, had set himself behind the wave and everything was visible. So much power in the turn. So many fins above the lip. So much water being flung in all directions. And I felt better.

I felt magical.