Ocean gives punk icon HR an anti-depressive lift!

HR strolled into the grand lobby of the Lord Baltimore hotel where he was awaiting the premiere of Finding Joseph I, the story of his rise, struggle, and return to Jamaican waters.

Selfishly, I wanted him to jump up onto the glass coffee table, unleash a desperate roar, then spring into a perfect backflip.

But HR, leader of the pioneering punk rock group Bad Brains is not this person. His gait is measured and at times uncertain. His words are few and gently drift out of a small sixty-one-year-old frame. He is fragile.

Yet somewhere in this man exists a history of all of us who heard his voice screaming inside our heads as we furiously paddled: CHARGE! It’s no coincidence that Bad Brains’ anthems brought life to countless surf videos; HR knows the ocean and its power.

HR still retains a bit of the unique style that attracted so many kids to him, his music, and his Positive Mental Attitude, or PMA, over the last four decades. Reclining in a silver Adidas track suit with matching shoes, Rasta-colored knit hat and fat gold watch — clasped outside of the sleeve, of course— he opens up.

But HR doesn’t share much about the watch, the music or the PMA. He talks about his first memories of swimming on the shores of Jamaica and playing in the waves of Hawaii.

He wants to talk about the ocean.

“When I was a boy living in Waikiki, I once dove into the water after a sailboat anchored way in the distance. I thought I could make it there underwater but quickly realized that I was drowning. I was too far from that boat and too far from shore,” he says. “Then I see my father dive in.”

HR closes his eyes and smiles. “He saved my life.”

Growing up on the beaches of Hawaii gave HR (Human Rights), born Paul Hudson, the opportunity to develop an intimate relationship with the water. He and brother Earl (also Bad Brains’ drummer) wanted to imitate the surfers they saw and idolized including the Duke, whom HR declares as his favorite.

The two boys shaped primitive skim boards with their father’s tools in the garage and spend their days throwing themselves into the shore break.

“They worked really good,” he explains as his eyes light up. “But, you know, it depended on who was riding them.”

HR laughs, a modest nod to his skills.

As HR entered adolescence, his father, an Air Force employee, began a string of short-term reassignments which removed the family from idyllic Hawaii to such inland locations as Texas, Alabama, and the New York City. While HR was no longer close to the ocean, his passion for the water remained. Settling in, HR joined his school’s diving team.

“I loved to dive. That’s where I learned to flip and I never stopped,” HR says referring to the lightning-powered acrobatics that would soon help define his onstage charisma. He excelled so rapidly that his school coach offered to train him for an Olympic bid.

“The coach asked my mom what she thought about me moving away to work with the Junior Olympic team,” HR recalls. “But she wasn’t havin’ it. I wanted it, but she said, ‘no way.’”

His mother knew that another reassignment was approaching. This time, HR would land in Washington, DC, home of the President and birthplace of the young Bad Brains.

And then came the music.

Album after furious album.

Touring and notoriety.

Madonna and her Maverick record label came calling.

Chris Blackwell, owner of Island Records, petitioned HR to play Bob Marley in an official bio-pic. There’s even an intriguing photo of a Cheshire-grinned HR aside a woman —curiously resembling Brooke Shields — drawing in a big lungful of something.

All the supposed glory of a rock star was within reach.

But HR wasn’t interested in money or fame.

While living in North San Diego County in the late 1990’s, HR was once again drawn to the water and rediscovered his habit of watching local surfers, the same routine as on the shores of Waikiki. Friends also claimed that around this time he also developed other, less-healthy habits.

As the rest of us moved on to middle-class prizes, he remained true to his words: “The bourgeoisie had better watch out for me,” HR sang.

What money he had, he spent or gave away. He rarely held a permanent address, bouncing from home to the street and on to the next, ping-ponging between the east coast and California.

While living in North San Diego County in the late 1990’s, HR was once again drawn to the water and rediscovered his habit of watching local surfers, the same routine as on the shores of Waikiki. Friends also claimed that around this time he also developed other, less-healthy habits.

There were stories and rumors. HR smokes crack. HR just plays games. HR is crazy. During his most troubled times, he could be seen shuffling around the streets costumed in a platinum-blond wig, gold slippers, flowing white bathrobe over a electric-green Adidas track suit, an acoustic guitar dragging behind him. A genuine tinfoil on-the-head departure from reality. An overwrought English accent layered his ravings about Princess Diana or Barack Obama possibly tapping his phone.

Like in the waters of Waikiki, HR once again needed saving.

In 2010, independent film-maker James Lathos learned that HR was sleeping in a boarded-up warehouse in downtown Baltimore.

“He was just surviving,” says Lathos. “It was not a healthy place.”

Lathos realized that he had an opportunity to do more than simply document the downfall of one of rock’s most mythical figures, he had the chance to bring him to the surface.

Lathos, a surfer, thought quickly.

“I had to get him out of the urban ghetto. So what better place than the ocean?”

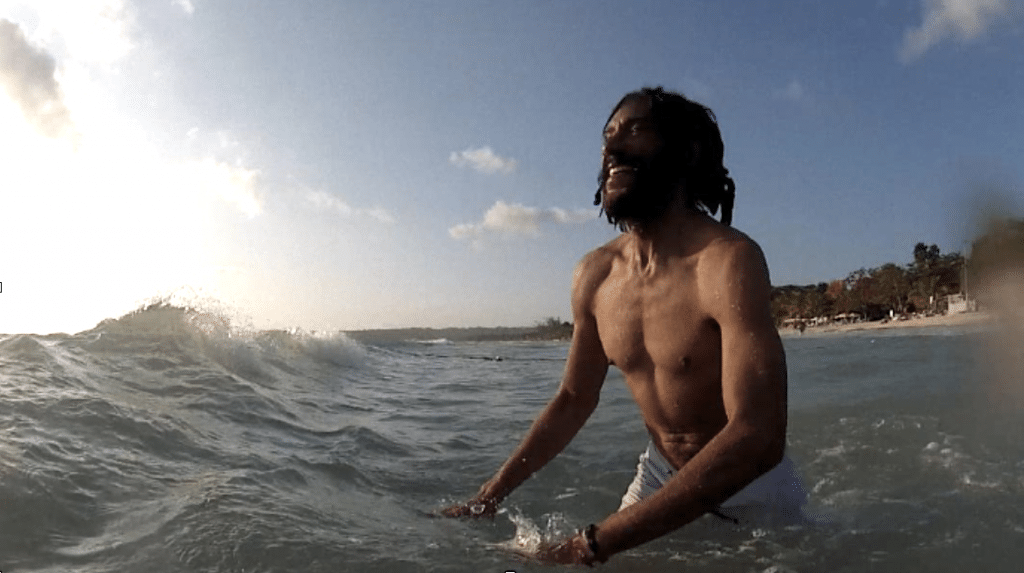

After securing the needed funds, the two traveled to Jamaica with a small crew to capture HR’s return to the waters where he first played.

“It was therapy,” says Lathos. “It’s a heavy burden to be him… to see him diving off the cliffs and swimming in the ocean was everything. You could see his spirit open. He felt free again.”

HR connects one satisfying word with his time back in the waves: “Happiness.”

And when I ask him if he attempted a backflip, HR replies, “No, I just dove straight down… but this time I came back up.”

It was his start to recovery.

Some things are better described than defined, and mental illness might be such a thing. The Jamaican trip may have been the spark for HR to seek medical help for his deteriorating mental state. Doctors found he displayed symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia. They also diagnosed him with SUNCT, a rare brain condition which causes debilitating and constant “icepick” headaches. Fortunately, doctors have been able to address both conditions.

Yet, this does not underscore the power of his ocean homecoming.

As Lathos saw it, “He was off the hellhole streets and happy, man. It was redemption.”

Lathos also sees a bigger picture. “I’m glad I could help my friend and if this movie, which shows HR’s struggles with mental illness, can help even three people, it’s worth it.” But the director-surfer digresses. “Of course, any chance to get in the water in Jamaica is worth it, too!”

Currently, HR is working with his Bad Brains bandmates on more material, ready to deliver the message of PMA to a new generation of kids charging into waves. In Finding Joseph I, HR confesses, “I was given a responsibility to be a leader, but I also had to be a human being” — a balance which might finally be reclaimed.