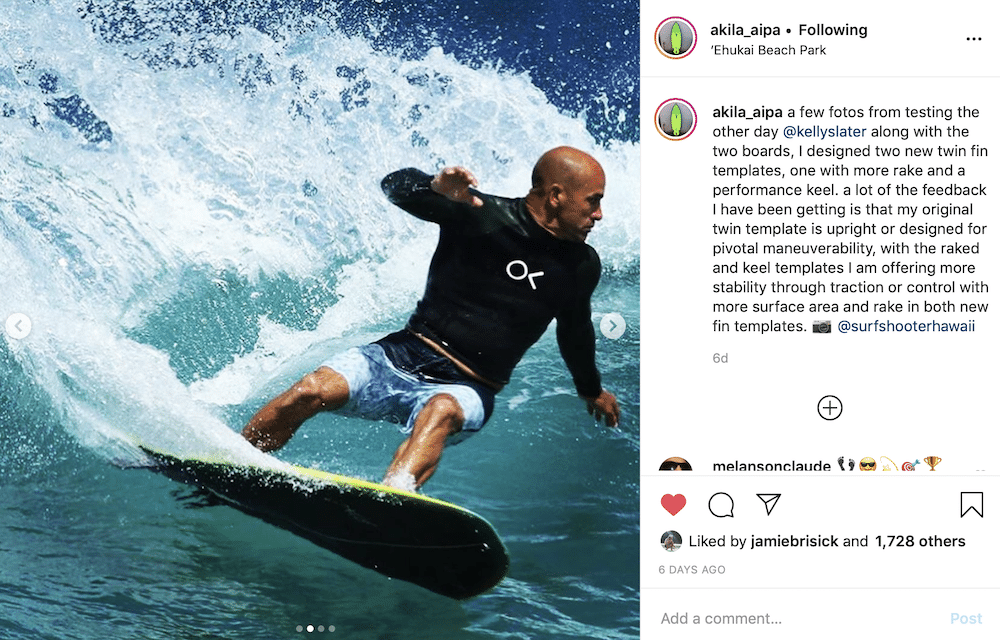

Two old friends get together to create a flashy Slater Designs twin-fin collab…

It ain’t a stretch to suggest that surfing’s genetic code, its great culture, has been weakened, maybe fatally maybe not, by the WSL’s VAL onslaught.

Just as the modern man is an invertebrate who frets over his Twitter posts and binge-watches television series with a tub of ice-cream balanced on his abdominal apron, the modern surfer has moved from sharpened surfboards to double-enders and from trekking through the Indonesian jungle to ride a wave that will tear his head off to wellness retreats with a surf-yoga component in dowdy sand-bottom rollers.

Akila Aipa, fifty this year, a former pro surfer from Hawaii and the son of the great surfer-shaper Ben Aipa, therefore, is not a man of this time.

He grew up with a front-row seat to the North Shore, with a famous, and famously loved Dad, chased contests briefly then settled into a life as a small-time shaper out of a factory near the Waialua Sugar Mill.

A rare soul connected to surfing’s cultural continuum.

Like Ben, Akila was doing it for the love, pretty much, and until recently, five hundred dollars would get you a version of the five-eight Kelly Slater used to beat hell out of Kerama last year, one of a seven-board quiver he’d made for his old friend.

As our tour correspondent reported, “Kelly leant back into a savage back foot heavy layback hook. It was the turn of the day. The turn of Kelly’s year. It lit a little candle of hope in the deep dark cave of Kelly’s retirement year.”

And as Kelly said at the time, “Akila…board is so lively and fun. I thought for sure it would be too low volume for me but it planes really well and just grabs speed from everywhere. Stoked. Unexpected. Can’t believe it took us this long to make a board.”

Akila appreciated the attention, a little spotlight on his three decades of shaving foam.

What he didn’t have, still doesn’t, was the manufacturing set-up to deal with the demand. He’d shaper a board, then outsource the rest of the production. His margins are tiny. Hundred bucks for a board on a good day.

So when I call on one of the last days of the Hawaiian winter to talk about his collaboration with Kelly on a twin-fin model for Slater Designs, it ain’t surprising to hear he’s been “walking the property” at a friend’s place that might serve as a new factory.

“Trying to make changes to grow,” he says. “What good is all that buzz if I can’t absorb it?”

Akila can talk but he doesn’t gush, another reason he’s not a man of this tremulous, pearl-clutching era.

I ask about the twin and he says, “Yeah, we’ve been poking around, we’ve been playing.”

I push a little.

Akila tells me Kelly has thickened, physically, ten pounds or so of muscle.

“Heavier than he’s ever been. Stronger and healthier than he’s ever been. He’s bulked up as a man. He’s learned to value that weight. And his equipment’s come along with that. He had a certain literage before and we have to come up with at least a litre or a litre-and-a-half. You can only push a sensitive board so far before you start babying it. He can ride a thicker board, lay into it and if he opens up and plays his power game, ooowee, fun shit!”

So for every ten pounds you add, your boards go up a litre?

Akila says yeah, warily, because he doesn’t want you to become obsessed by your supposed perfect literage number.

“It’s become this security blanket thing,” he says. “Know your numbers, your dimensions.”

Akila likes working with Kelly because, “He’s invested, man, he’s not afraid to try shit. You give him a wild board and he doesn’t rip it apart and discredit it.”

For Snapper, Akila has made Kelly three boards, a five-eight twin, a five-five and a five-ten.

“Is it going to be barrelling or running? That squash we did for Keramas was a five-eight, he came up two inches, which dialled in that extra litre. It was a natural volume gain just by going up in inches. We’re looking for a longer rail line so he can push it and hold it longer. The five-eight has a breaking point where it disengages. At J-Bay that could be a disadvantage. I want him to have the five-ten in case it’s five foot and there are faces to gouge. These days, everything’s so specialised and Kelly’s an out-of-the-box dude. The thing about surfing is its expression. When you’re performing, take the thing that gives you the freedom to perform and express. If we don’t know what brush he wants to paint with, provide all the brushes.”

Akila laughs.

“I don’t overthink this shit. Fun boards, fun designs are the most important thing. If you’re making five percent gains instead of rewriting the book each time, try not to overthink it. Live in the moment, let the designs evolve.”

How articulate is Kelly during the design process?

Akila shoots back. “What do you think?”

Well, I say, I imagine he would be rather finicky, sensitive to changes and able to communicate his findings in detail.

“He’s an articulate dude, right. If he’s open and wanting to give up his time he’ll go there. If it’s short and simple he’ll be short and simple. He won’t try and get intricate if it’s not working. If it’s wrong we’ll get to it right away.”

No pals during the design process either.

“Gotta be able to handle that good and bad and don’t take it personally,” says Akila. “We’ll drink a beer and golf and be friends and then, like this week, we’ll come to the table, put time in and work.”

Kelly, says Akila, is one of the, maybe…the…”deepest thinker and surfer on the planet. I don’t take that lightly. I don’t want to waste that time. I don’t want to take him in circles. It’s not a hamster wheel. Let’s nail shit. When he gives you something, you know there’s thought and a process behind it. Who doesn’t appreciate that? The designer has to be open, vulnerable and able to handle that and adjust to it. It’s a working relationship and it’s fun as shit.”

Akila hoots.

“It’s a body of work, man!”

The twin he and Kelly are working on, and which’ll slide into the Slater Designs range later this year, maybe summer 2020, isn’t the monster swallow, crescent-moon fin things you ride on chubby points and nurse along waves everywhere else.

Still, it is going to be a board most of us can shred a little on.

“Everything’s pretty subtle,” says Akila. “He knows and I know that it has to be replicated on scale, across all sizes and be as user-friendly as possible. As intricate thinkers as we are, we’re not so left-field to make a board surfer will struggle with. The consumer has to feel gains from it.”

Right now, it’s testing, hitting the factory, then testing some more in the North Shore wave park.

“We want to test it enough, make enough prototypes that if someone surfs it they’ll think it’s pretty fucking cool. If it’s not good and they don’t appreciate it, why would I want to do it? A lot of thought and input and research and R and D before we release it. We’re not making cookie batches here. We’re close to where we wanna be. I’m a nerd with this shit. If my name’s on it, I’m not going to release it in a hurry.”

The tech, whether it’s PU and epoxy, is yet to be decided. Akila wants the design to be perfected before anything else. He appreciates who he’s working with, however, and would be pretty thrilled to maybe develop tech using hemp resins.

Last time we spoke, a little less than a year ago, you could buy an Aipa for five-hundred dollars and if you lived in Australia, he’d give a flight attendant pal fifty bucks to deliver it to you.

A ridiculous price, you’d think. How does he do it etc.

Today, Akila charges seven-hundred dollars a board.

“I was cheap too long,” he says. “I’m blue-collar. People could afford my local prices. I’ve got some flack for putting the price up. What they’re not seeing are the changes I’m making to be better and the price reflects that. It allows me to own my own machine, a factory, have quality control. Here’s the thing, I’ve been shaping for thirty years. The price should reflect that. I was working by myself. Now I have a small staff, I gotta pay for that. My board didn’t pay for no machine, didn’t pay for shit! That’s what the price reflects. Better boards, a better brand.”

I ask Akila about his famous Dad, now almost seventy-eight, a former linebacker who didn’t start surfing seriously until he was twenty, but got good real fast, the inventor of the swallow tail, the stinger.

Ben caught a blood infection in hospital a while back. Beat him up bad.

“Dad, he’s slow,” says Akila. “He’s on a recovery path. He’s living simply with this wife. I’m just stoked my son has a grandpa.”

A sigh followed by a loud laugh.

“Every day above the ground is a good day. Any age. We’ll take it. I’m learning that.”