Academics have found status in a system that rewards a political agenda. Their fantasies would evaporate if they had to deal with reality.

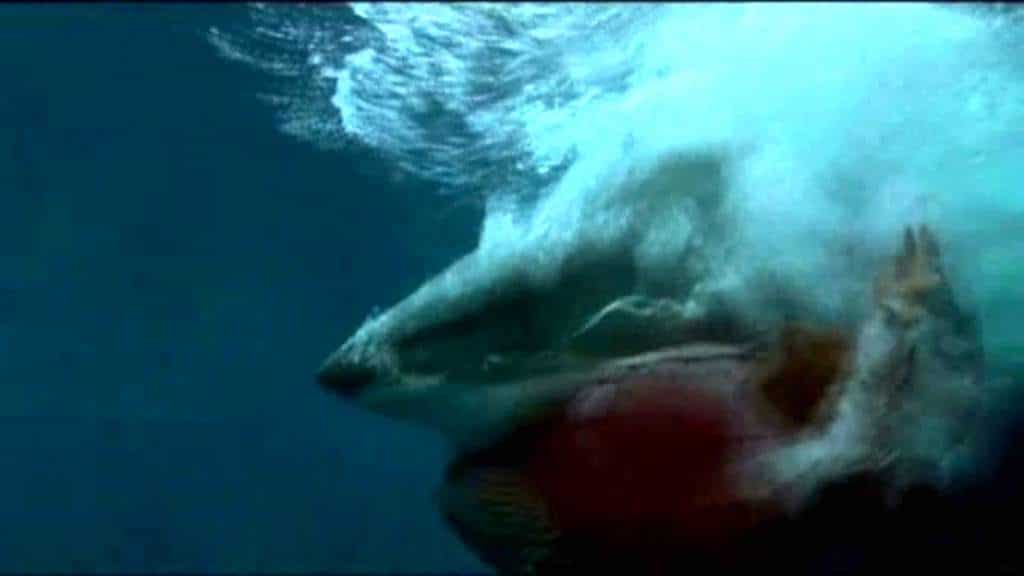

Politics never interested me until a spate of shark attacks occurred at my local Ballina beach next to the rivermouth in 2015 and 2016.

Two of these attacks took place while I was surfing, one right in front of me. Over a period of two years, twelve shark attacks occurred along a 70 kilometre stretch of coast, eight within ten kilometres of Ballina, four within a kilometre of the river mouth. Two of the attacks were fatal.

Needless to say, the surfing community was traumatised, but so too was the community at large. The ominous sounds of ambulances and helicopters haunted the coastal strip, as journalists and film crews kept the story in the headlines.

Just like the pandemic, we spent two years talking about nothing else. It was difficult to continue surfing. But, with so few people braving the ocean, it was hard to resist the temptation.

A sense of camaraderie developed among the local surfers, partly because we were having so much fun surfing uncrowded waves, and partly because any one of us might suddenly need help getting to shore.

As far as I know, I was the only one using a costly and cumbersome electrical device mounted on my board to deter sharks. Others painted their boards with stripes to look like venomous sea snakes. While most surfed without any form of deterrent, everyone stuck together, feeling safer in numbers.

When I asked the lead author, Corey Bradshaw, why he anticipates human-shark interactions to follow this pattern, he replied: “It’s in the paper – long-term fluctuations of climate patterns in the ocean. Exact mechanism? Unsure.”

So, I tried again.

“Thanks. But, if you cannot identify the exact mechanism, then how could you be confident that your modelling reflects reality? I don’t doubt the gradual increase depicted over the next decade, since both populations are increasing. But, why wouldn’t it continue rising indefinitely? It seems unlikely that the rate of attacks would decline, as you predict.”

The conversation ended there. He is a busy man, with a tremendous vision for humanity.

According to his modelling, about 1,800 people could fall victim to shark attack in Australia over the next 45 years. But, if his hypothesis is incorrect and the rate of attacks continues to rise at the current rate, there will be an additional 800 victims. This means the number of attacks in 2066 will be more than double his prediction for that year.

How many tragedies have to occur before someone in power finally says enough is enough? The government body tasked with reducing the rate of shark attacks has deployed a suite of measures, which is elaborate and costly, but does little to solve the problem. As far as they are concerned, reducing the population of sharks is not an option.

You really have to wonder if they care more about sharks than people. If that is the case, then the problem is the anti-human agenda of environmentalism.

Despite being a world-renowned ethicist, whose seminal work inspired the animal rights movement, Peter Singer has somehow managed to avoid the shark debate raging in his home country, not even appearing at a Senate inquiry into the problem. This is the guy who spent his whole life rationalising values to suit the greater good, only to change his mind when faced with the uncomfortable decision of his mother’s passing, finally conceding that “Perhaps it is more difficult than I thought before, because it is different when it’s your mother.”

I guess that is the problem with many intellectuals. Enamoured by the rational mind, they lose touch with their humanity.

This problem is also evident among surfing academics, whose devotion to nature provides a convenient distraction from the messy business of real life. For example, Rebecca Olive views the risk of shark attack through the prism of eco-feminism, which she explains “questions the assumed authority of humans over … all the non-human elements that make up the worlds we live in”. She confesses to being afraid of sharks, but reckons feeling vulnerable evokes a profound sense of communion with nature.

When I saw two young surfers paddle straight up to their friend after he had been attacked by a shark, it occurred to me that men have been protecting each other like that since the dawn of time.

The bravery exhibited by those boys had more to do with nature than any worldview contrived by eco-feminists. It is in man’s nature to protect the clan.

These academics have found status in a system that rewards a political agenda and punishes opposition.

They rarely face any pushback.

Their self-indulgent fantasies would evaporate if they had to deal with reality.

How many privileges do they take for granted?

It is despicable that the most privileged people to have ever lived are so hell-bent on destroying the very culture that supports them.

But, they have been programmed to think in a certain way, which not only subordinates the individual to the group, but humanity to the environment.

They are the “useful idiots” carrying the Trojan Horse of socialism disguised as identity politics and environmentalism.