But likes to fight! "Raging drunk, (he) staggered over to Sam George intending to beat the shit out of him, and had to be pulled away."

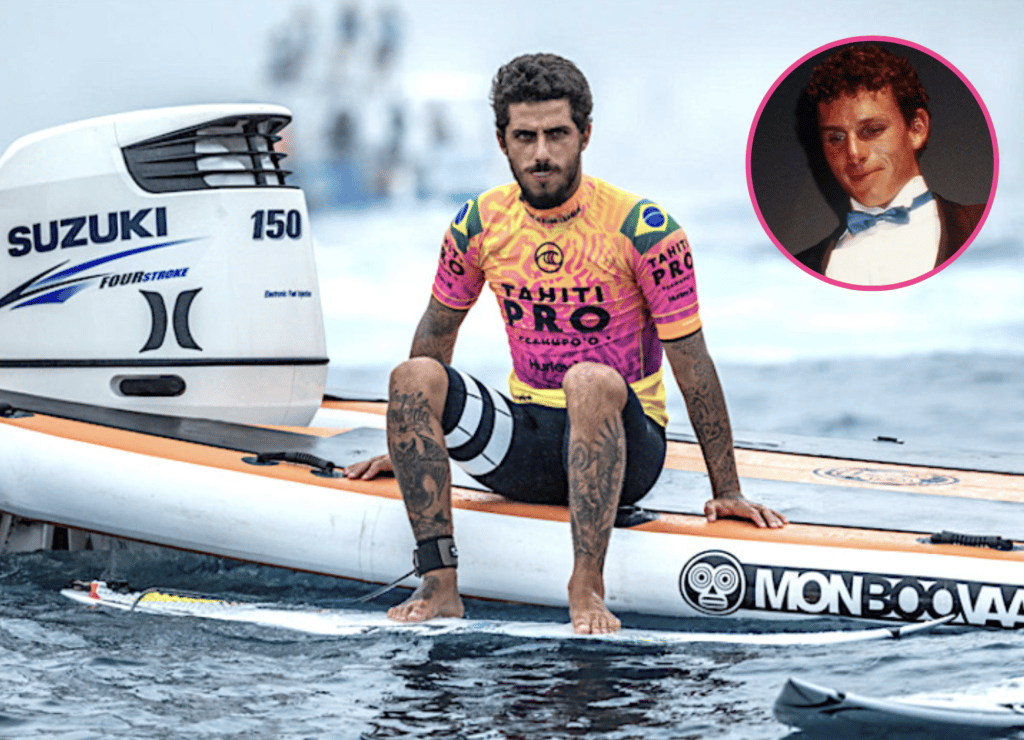

Last week I mentioned Damien Hardman, two-time WCT champ (1987, 1991) from Narrabeen, and Filipe Toledo as the two male title-holders most lacking in big-wave credibility.

If anything, I felt we’d been crueler to Toledo.

Boy, was I wrong. Hardman got it so much worse.

The opening of Damien’s first SURFER profile, in 1988, written by Phil Jarratt just after Hardman won his first title, reads as follows:

Never having met Damien Hardman—the man who would soon become world champion—I asked around about him. “He’s kinda like Simon Anderson in his approach to life,” said one person. “It’s that Narrabeen thing, I suppose. But I wouldn’t put Damien in Simon’s class. He hasn’t got the brawn or the brains.” I asked someone else whose opinion I respected if he thought Damien would take the title. He said: “Damien just hasn’t got the balls to go all the way.”

After making the obvious point that Hardman had defied expectations to win the title, and then highlighting the new champ’s grit and tenacity, Jarratt seems to lose interest, with vague praise about Damien’s recent championship death-match heat against Gary Elkerton at Manly Beach, and an exit line in which Hardman promises to be a “good ambassador” for surfing. Jarratt, by nature a playful and engaged writer, was clearly bored.

Ten years later, with Hardman still a world title contender at age 33, pop culture diva Cintra Wilson, in her coverage of the French leg of the 1999 WCT, called him pro surfing’s “Evil Stepdad.”

A two-time former world champion and Occy’s biggest threat to this year’s championship, [Hardman] is monstrously capable but strangely cursed to be the Richard Nixon of the surfing world. He’s rigid with media unlovability, broody, uncute and super ambitious. He also colors inside the lines and racks up the points by being a ruthless and precise techno-surgeon. The Iceman is coldly serious and basically impossible for teenage girls to get a crush on.

Hardman had zero interest in being a surf media personality. Which makes sense, given the way he was treated. It’s a chicken-or-egg question. None of the surf writers of the period looked much past the fact that Damien was from Narrabeen, that he didn’t perform in big surf, and that he was a grim, methodical, merciless competitor. Rarely mentioned was the fact that, on his best days, Hardman was as frictionless in the water as George Gervin was on the hardwood. Maybe we iced him, in other words, not the other way around.

In 2001, the just-retired Damien Hardman was a judge Op Pro Mentawai Islands specialty event, which I covered, and which ended up being my one and only Indo boat trip.

There was a short bus ride at some early point in the gathering, while we were still on Sumantra, and when I was reintroduced to Hardman—we’d met a few times in the 1980s—he just nodded and looked away.

We loaded into a trio of boats, one for the six male competitors, another for the four women competitors, and another for media and judges. Damien, not surprisingly, bailed off our boat and stayed with the surfers.

It was an amazing time.

We floated and lounged and surfed, ate well, ran the event, and stayed out there for a week or so before returning to port. My two most distinct memories of Damien both come from that trip.

First, near the end of an all-hands party one evening on our boat (which was biggest), Damien, raging drunk, staggered over to Sam George intending to beat the shit out of him, and had to be pulled away.

Sam had done nothing to provoke Damien. I don’t think Damien even knew who he was talking to at the moment; Sam was a ranking surf media figure, a stand-in for all of us, and that was enough.

Second, Op had secured some kind of Indonesian governmental permit that allowed us to clear the water at any break we chose. Which sounds incredible, but was in fact weird and wrong and depressing.

A pair of surfers out alone at Bank Vaults when our flotilla pulled up, the first day of our trip, and dropped anchor. They were called in. Twenty years later I remember the looks on their faces—confusion fermenting into anger—and feel ashamed.

But of course it didn’t stop us, we did the same thing day after day, and eventually that was how Damien Hardman and I ended up out alone in perfect overheard surf at Macaronis.

It was the second-to-last day of the trip. The contest had just finished (Mark Occhilupo and Keala Kennelly won), at which point Damien and I, at the exact same moment but from different boats, darted into the lineup.

A decision had already been made to motor north to catch Hollow Trees before dark, and the other surfers from our group were already aboard the boats, which were now idling in the channel.

My thought was to grab a wave or two before we left. I did, but then sneak-paddled back into the lineup because if it wasn’t the absolute best surf I’d ever seen, it was without question the best uncrowded surf I’d ever seen.

Damien was sitting there when I returned.

We looked at each other, and he wasn’t the Iceman or the two-time champ or a media-hating drunk—he was the person who could extend this perfect moment.

Some version of the same thought ran through Damien’s head, “I will if you will,” he said, or some variation thereof, and over the next 20 semi-illicit minutes I caught another three waves, and maybe I am a cheap date but that is how Damien Hardman warmed my heart.

(You like this? Matt Warshaw delivers a surf essay every Sunday, PST. All of ’em a pleasure to read. Maybe time to subscribe to Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing, yeah? Three bucks a month.)